With the release of Mathematica 8 today, the single most dramatic change is that you don’t have to communicate with Mathematica in the Mathematica language any more: you can just use free-form English instead.

Wolfram|Alpha has pioneered the concept of specifying computations with free-form linguistic input. And with Mathematica 8, the powerful methods of Wolfram|Alpha become available within the Mathematica environment.

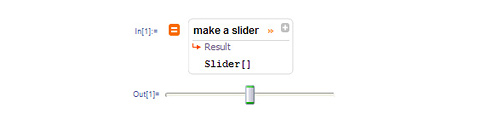

All one has to do is to type an = at the beginning of a line. Then what follows is taken as free-form linguistic input.

You don’t have to use precise Mathematica syntax. You can type things in just the way you think about them, in free-form English. But what happens is that Mathematica calls on Wolfram|Alpha to try to interpret your input, and turn it into precise Mathematica code.

In their native forms, Wolfram|Alpha and Mathematica operate in very different ways. Wolfram|Alpha takes free-form linguistic input, and lets you make quick, single, queries. Mathematica requires you to use its precise formal language, but lets you build up programs and computations of arbitrary complexity.

The exciting thing that’s now happened with Mathematica 8 is that these very different approaches have been brought together—to produce the best of both worlds. One has the freedom and breadth of expression of Wolfram|Alpha. Yet one can build things up with the precision and structure of Mathematica.

For Mathematica beginners, free-form linguistic input has an obvious and dramatic effect. You can just start typing, however you think about things, and Mathematica should automatically be able to understand you.

By watching what it does, you’ll probably pretty soon get the hang of Mathematica‘s own native language. And sometimes you’ll choose to enter your input in that; sometimes you’ll want to just use free-form linguistics.

I consider myself a very expert user of Mathematica, and I know the Mathematica language very well. But I’ve been surprised to see that in all sorts of cases, I’m choosing to use free-form linguistic input.

Sometimes it’s because I can’t quite remember how some particular Mathematica function works in some area that I don’t use very often. Sometimes it’s to pick up the standard Mathematica name of some data object, like a city or a country or a chemical.

And sometimes it’s just faster to enter sloppy free-form linguistics for something I want to do, and let Wolfram|Alpha figure out a reasonable choice of details to fill in.

At first, I thought one might mostly just use free-form linguistics for one-shot computations: a little like just having access to the Wolfram|Alpha website from inside Mathematica.

But what I quickly realized (after a very long and difficult process of designing the underlying functionality, I might add) is that that’s not correct. Instead, I routinely found myself using free-form linguistics as an integral part of longer computations—randomly interspersing Mathematica syntax and free-form linguistics on different lines in a Mathematica session, and just using whichever was most convenient for a particular input.

And here’s an exciting part: in Mathematica 8 the free-form linguistics doesn’t just operate line-by-line. It knows the context in which it’s used in a notebook, so you can use it to build things up.

You can start with a plot:

Then you can add something to it.

Or do image processing on the result.

In each case, the Wolfram|Alpha engine will synthesize Mathematica code to do what you asked, then apply this code to the result you had before.

Well, this is the beginning of something very remarkable: the ability to do programming with free-form linguistic input.

We’re just at the beginning of this process. But already the Wolfram|Alpha engine can handle a wide variety of Mathematica concepts. Like list manipulation, image processing, string manipulation, import-export, and even user interface construction.

And the engine can also deal with variables that exist in your Mathematica session, so you can refer to them by name inside free-form linguistic inputs.

I think this is all a pretty big deal. You see, in the past, if you wanted to do any serious programming, you really had no choice but to learn a precise formal programming language. But now you can just tell the computer what you want to do using plain English.

And the big effect of this is going to be that the barrier between programmers and non-programmers will come down. Everyone is going to be able to be a programmer.

Right now we’re just at the beginning of having the Wolfram|Alpha engine understand all the different things one might want to do with programs. But from what we can already see, it’s quite clear that the concept is going to be very general. Building on the big tower of technology that is Wolfram|Alpha, we’re going to progressively be able to make more and more of programming accessible through plain natural language.

There are so many exciting things about this. To mention one: in the past one had to distinguish plain English “comments” from actual, active, code. But now, with free-form linguistics, one can have a plain English description that just automatically turns into active code.

Of course, if you’ve given some vague free-form linguistic input, the Wolfram|Alpha engine may not be able to figure out precisely what you want to do. But the great thing is that you’ll always be able to see—and check—what the engine thought you wanted to do. Because you’ll see the precise Mathematica code it’s generated. And because Mathematica is such a succinct and readable language, it’ll usually be quite easy to tell what precisely that code will do.

So how does free-form linguistic input really work in a Mathematica session?

Anything you type after = is sent over the internet to a Wolfram|Alpha server, which tries to generate a Mathematica interpretation of it. Assuming it succeeds, that interpretation is sent back to Mathematica, and evaluated locally in your Mathematica session.

When your input is sent to the server (unless you’ve set preferences to prevent this) some information on the local context in your Mathematica notebook is sent along as well—to let the Wolfram|Alpha engine know what you might mean by “the image” or the name of a variable that you’re using.

Needless to say, to use the Wolfram|Alpha engine you have to have a connection to the network. For large secure facilities and the like, we’ve actually developed a Wolfram|Alpha appliance that operates as an onsite “private compute cloud”. But mostly we just assume that in the modern world most people are going to have access to the internet from their computers most of the time.

Well, here’s another issue: what if the input you give just doesn’t have any reasonable interpretation in Mathematica, or can’t give any reasonable output in Mathematica? Here’s what happens then:

The output you get is what we affectionately call an “Alpha blob”—an inert object that represents the result of your computation as generated by Wolfram|Alpha. Inside the Mathematica notebook, you can copy and paste from inside this “blob”, or you can use standard Mathematica functions to extract pieces of it. You can also often feed it back as part of a piece of free-form linguistic input.

Most of the time, you’ll be able to use = without thinking much about Wolfram|Alpha. But sometimes it’ll be useful to see the Wolfram|Alpha perspective.

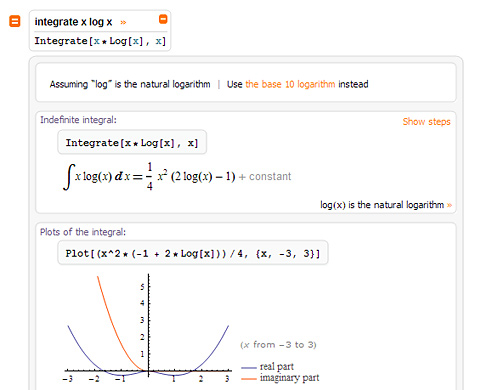

One important difference between Mathematica and Wolfram|Alpha is that while Mathematica always gives a single output result from a particular input, Wolfram|Alpha typically gives many different output pods.

Within Mathematica, you can see the complete collection—pretty much as they would appear on the website—by clicking the orange +.

By default, Mathematica will automatically pick a pod to return—typically either the “Input interpretation” pod, or the “Result”, if there is one. And the pod that Mathematica chooses is indicated by an orange arrow.

But you choose another pod by clicking it. Then you can actually use that pod by re-evaluating the input using Shift-Enter.

Another reason to expose the whole Wolfram|Alpha-style output is to handle disambiguation of inputs. Let’s say you enter “springfield” as your input. On the Wolfram|Alpha website, you’ll see something that tells you which Springfield Wolfram|Alpha is assuming you mean, then gives you a way to choose a different Springfield.

If you need to choose a different Springfield inside Mathematica, you can do this by exposing the pods using the +, then clicking the appropriate assumption.

In addition to =, Mathematica 8 lets you type == at the beginning of a line. When you do this, you’ll see the icon change from an orange square, to an orange “Spikey”. And what happens in this case is that instead of getting a single Mathematica-style result, you’ll immediately get a whole Wolfram|Alpha result, with its complete sequence of pods.

In this form, there are little gray + icons in each pod. Clicking these gives a menu specifying each of the possible forms in which the contents of the pod can be interpreted.

Underlying the whole = and == mechanism is the WolframAlpha function in Mathematica, which is a programmatic way to interface to Wolfram|Alpha, based on the Wolfram|Alpha API. You can use the Wolfram|Alpha function not only to handle linguistics, but also to do things like get data from Wolfram|Alpha.

It’s worth realizing that when you use == inside Mathematica, you’re getting much richer results than you do on a website. Because everything is represented symbolically inside a Mathematica notebook, you can readily manipulate graphics—for example rotating 3D objects—and copy and paste any piece of output.

When used inside Mathematica, Wolfram|Alpha also sometimes generates Manipulate[ ] constructs, allowing immediate dynamic interactivity—that is efficiently executed on your computer rather than the Wolfram|Alpha servers.

When you open a notebook in Mathematica 8, there’s an immediate visual clue that something new is possible:

![]()

Clicking this gives a menu:

And from the menu you can select ordinary Mathematica language input, or free-form linguistics—or plain text.

There’s one more case that’s really convenient in writing programs in Mathematica—control-=.

The idea of control-= is to provide an inline linguistic assistant. It only handles linguistics that’s directly translatable to Mathematica syntax (since it has no place to put anything else). But assuming that there is a Mathematica translation, within a control-= region you just have to type Return to get it.

Typically control-= will produce a “double-decker” form, containing both the free-form linguistic input, and the Mathematica language form. You can leave this double-decker form—as a kind of “self documenting object”—and Mathematica will interpret it by looking only at the Mathematica language form. Or you can click the upper or lower “decks” to show only one “deck”.

After working on Mathematica for a couple of decades, it was a strange experience to be working on Wolfram|Alpha. For its design criteria were almost the exact opposite of Mathematica. In Mathematica, there is a precise language, which I have gone to great effort to keep as clean and simple as possible. But in Wolfram|Alpha the whole point is to deal with all the arbitrary messiness of actual human expression, effectively throwing in as much complexity as possible.

At first in working on Wolfram|Alpha I consciously tried to avoid thinking about how it might fit with Mathematica—to give it in a sense room to grow on its own. But once the character of Wolfram|Alpha was established, I began to think very hard about how it could be connected—and unified—with Mathematica.

There were many issues. What to do about the fact that Wolfram|Alpha gives many results, but Mathematica sessions have one result for each input. How to deal with ambiguities in Wolfram|Alpha inputs. What to do when Wolfram|Alpha does computations that are not built in to Mathematica. And so on.

But gradually as we worked through these issues, we began to see that a wonderful unification could be achieved—in which in a sense the power of both Mathematica and Wolfram|Alpha would be greatly amplified.

I have to say that I was somewhat skeptical about our ability to make Wolfram|Alpha understand not just what amount to queries for knowledge, but also programs and commands. And certainly we are just at the beginning of being able to do this—and over the weeks and months and years to come we will continuously try to update and improve it.

But I have been most encouraged by how far we have already been able to get. And indeed I have noticed that I myself have now routinely started to rely on free-form linguistics whenever I use Mathematica.

The arrival of free-form linguistics will surely forever change how Mathematica is used, and learned. After nearly a quarter of a century, we have today a fundamentally new way to communicate with Mathematica. We cannot yet foresee all the consequences, but it is already clear that this is something tremendously important.