One day I’m sure everyone will routinely collect all sorts of data about themselves. But because I’ve been interested in data for a very long time, I started doing this long ago. I actually assumed lots of other people were doing it too, but apparently they were not. And so now I have what is probably one of the world’s largest collections of personal data.

Every day—in an effort at “self awareness”—I have automated systems send me a few emails about the day before. But even though I’ve been accumulating data for years—and always meant to analyze it—I’ve never actually gotten around to doing it. But with Mathematica and the automated data analysis capabilities we just released in Wolfram|Alpha Pro, I thought now would be a good time to finally try taking a look—and to use myself as an experimental subject for studying what one might call “personal analytics”.

Let’s start off talking about email. I have a complete archive of all my email going back to 1989—a year after Mathematica was released, and two years after I founded Wolfram Research. Here’s a plot with a dot showing the time of each of the third of a million emails I’ve sent since 1989:

The first thing one sees from this plot is that, yes, I’ve been busy. And for more than 20 years, I’ve been sending emails throughout my waking day, albeit with a little dip around dinner time. The big gap each day comes from when I was asleep. And for the last decade, the plot shows I’ve been pretty consistent, going to sleep around 3am ET, and getting up around 11am (yes, I’m something of a night owl). (The stripe in summer 2009 is a trip to Europe.)

But what about the 1990s? Well, that was when I spent a decade as something of a hermit, working very hard on A New Kind of Science. And the plot makes it very clear why in the late 1990s when one of my children was asked for an example of “being nocturnal” they gave me. The rather dramatic discontinuity in 2002 is the moment when A New Kind of Science was finally finished, and I could start leading a different kind of life.

So what about other features of the plot? Some line up with identifiable events and trends in my life, sometimes reflected in my online scrapbook or timeline. Others at first I don’t understand at all—until a quick search of my email archive jogs my memory. It’s very convenient that I can always drill down and read a raw email. Because as with essentially any long-timescale data project, there are all kinds of glitches (here like misformatted email headers, unset computer clocks, and untagged automated mailings) that have to be found and systematically corrected for before one has consistent data to analyze. And before, in this case, I can trust that any dots in the middle of the night are actually times I woke up and sent email (which is nowadays very rare).

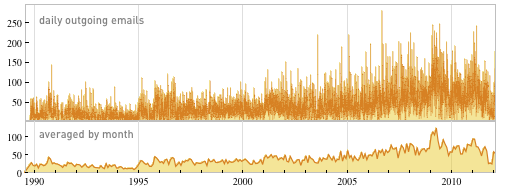

The plot above suggests that there’s been a progressive increase in my email volume over the years. One can see that more explicitly if one just plots the total number of emails I’ve sent as a function of time:

Again, there are some life trends visible. The gradual decrease in the early 1990s reflects me reducing my involvement in day-to-day management of our company to concentrate on basic science. The increase in the 2000s is me jumping back in, and driving more and more company projects. And the peak in early 2009 reflects with the final preparations for the launch of Wolfram|Alpha. (The individual spikes, including the all-time winner August 27, 2006, are mostly weekend or travel days specifically spent “grinding down” email backlogs.)

The plots above seem to support the idea that “life’s complicated”. But if one aggregates the data a bit, it’s easy to end up with plots that seem like they could just be the result of some simple physics experiment. Like here’s the distribution of the number of emails I’ve sent per day since 1989:

What is this distribution? Is there a simple model for it? I don’t know. Wolfram|Alpha Pro tells us that the best fit it finds is to a geometric distribution. But it officially rejects that fit. Still, at least the tail seems—as so often—to follow a power law. And perhaps that’s telling me something about myself, though I have to say I don’t know what.

The vast majority of these recipients are people or mailgroups within our company. And I suspect the overall growth is a reflection of both the increasing number of people at the company, and the increasing number of projects in which I and our company are involved. The peaks are often associated with intense early-stage projects, where I am directly interacting with lots of people, and there isn’t yet a well-organized management structure in place. I don’t quite understand the recent decrease, considering that the number of projects is at an all-time high. I’m just hoping it reflects better organization and management…

OK, so all of that is about email I’ve sent. What about email I’ve received? Here’s a plot comparing my incoming and outgoing email:

The peaks in 1996 and 2009 are both associated with the later phases of big projects (Mathematica 3 and the launch of Wolfram|Alpha) where I was watching all sorts of details, often using email-based automated systems.

OK. So email is one kind of data I’ve systematically archived. And there’s a huge amount that can be learned from that. Another kind of data that I’ve been collecting is keystrokes. For many years, I’ve captured every keystroke I’ve typed—now more than 100 million of them:

There are all kinds of detailed facts to extract: like that the average fraction of keys I type that are backspaces has consistently been about 7% (I had no idea it was so high!). Or how my habits in using different computers and applications have changed. And looking at the daily totals, I can see spikes of writing activity—typically associated with creating longer documents (including blog posts). But at least at an overall level things like the plots above look similar for keystrokes and email.

What about other measures of activity? My automated systems have been quietly archiving lots of them for years. And for example this shows the times of events that have appeared in my calendar:

The changes over the years reflect quite directly things going on in my life. Before 2002 I was doing a lot of solitary work, particularly on A New Kind of Science, and having only a few scheduled meetings. But then as I initiated more and more new projects at our company, and took a more and more structured approach to managing them, one can see more and more meetings getting filled in. Though my “family dinner stripe” remains clearly visible.

Here’s a plot of the daily average total number of meetings (and other calendar events) that I’ve done over the years:

The trend is pretty clear. And it reflects the fact that in the past decade or so I’ve gradually learned to work better “in public”, efficiently figuring things out while interacting with groups of people—which I’ve discovered makes me much more effective both at using other people’s expertise and at delegating things that have to be done.

It often surprises people when I tell them this, but since 1991 I’ve been a remote CEO, interacting with my company almost exclusively just by email and phone (usually with screensharing). (No, I don’t find videoconferencing with the company very useful, and the telepresence robot I got recently has mostly been standing idle.)

So phone calls are another source of data for me. And here’s a plot of the times of calls I’ve made (the gray regions are missing data):

Yes, I spend many hours on the phone each day:

And this shows how the probability to find me on the phone varies during the day:

This is averaged over all days for the last several years, and in fact I’m guessing that the “peak weekday probability” would actually be even higher than 70% if the average excluded days when I’m away for one reason or another.

Here’s another way to look at the data—this shows the probability for calls to start at a given time:

There’s a curious pattern of peaks—near hours and half-hours. And of course those occur because many phone calls are scheduled at those times. Which means that if one plots meeting start times and phone call start times one sees a strong correlation:

I was curious just how strong this correlation is: in effect just how scheduled all those calls are. And looking at the data I found that at least for my external phone meetings at least half of them do indeed start within 2 minutes of their appointed times. For internal meetings—which tend to involve more people, and which I normally have scheduled back-to-back—there’s a somewhat broader distribution, shown on the left.

I was curious just how strong this correlation is: in effect just how scheduled all those calls are. And looking at the data I found that at least for my external phone meetings at least half of them do indeed start within 2 minutes of their appointed times. For internal meetings—which tend to involve more people, and which I normally have scheduled back-to-back—there’s a somewhat broader distribution, shown on the left.

When one looks at the distribution of call durations one sees a kind of “physics-like” background shape, but on top of that there’s the “obviously human” peak at the 1-hour mark, associated with meetings that are scheduled to be an hour long.

When one looks at the distribution of call durations one sees a kind of “physics-like” background shape, but on top of that there’s the “obviously human” peak at the 1-hour mark, associated with meetings that are scheduled to be an hour long.

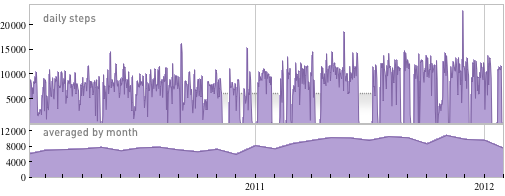

So far everything we’ve talked about has measured intellectual activity. But I’ve also got data on physical activity. Like for the past couple of years I’ve been wearing a little digital pedometer that measures every step I take:

And once again, this shows quite a bit of consistency. I take about the same number of steps every day. And many of them are taken in a block early in my day (typically coinciding with the first couple of meetings I do). There’s no mystery to this: years ago I decided I should take some exercise each day, so I set up a computer and phone to use while walking on a treadmill. (Yes, with the correct ergonomic arrangement one can type and use a mouse just fine while walking on a treadmill, at least up to—for me—a speed of about 2.5 mph.)

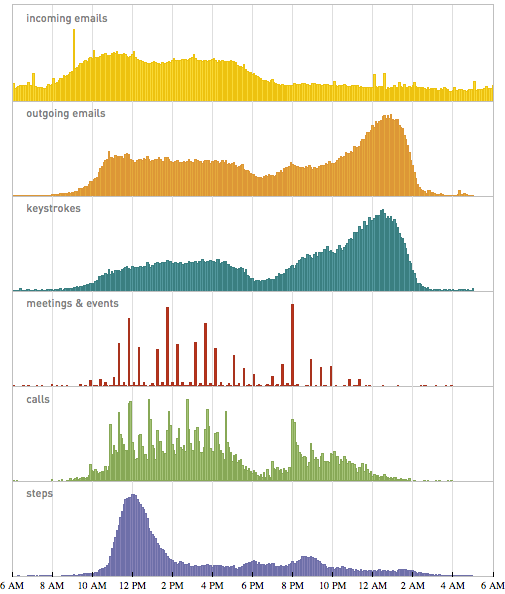

OK, so let’s put all this together. Here are my “average daily rhythms” for the past decade (or in some cases, slightly less):

The overall pattern is fairly clear. It’s meetings and collaborative work during the day, a dinner-time break, more meetings and collaborative work, and then in the later evening more work on my own. I have to say that looking at all this data I am struck by how shockingly regular many aspects of it are. But in general I am happy to see it. For my consistent experience has been that the more routine I can make the basic practical aspects of my life, the more I am able to be energetic—and spontaneous—about intellectual and other things.

And for me one of the objectives is to have ideas, and hopefully good ones. So can personal analytics help me measure the rate at which that happens?

It might seem very difficult. But as a simple approximation, one can imagine seeing at what rate one starts using new concepts, by looking at when one starts using new words or other linguistic constructs. Inevitably there are tricky issues in identifying genuine new “words” etc. (though for example I have managed to determine that when it comes to ordinary English words, I’ve typed about 33,000 distinct ones in the past decade). If one restricts to a particular domain, things become a bit easier, and here for example is a plot showing when names of what are now Mathematica functions first appeared in my outgoing email:

The spike at the beginning is an artifact, reflecting pre-existing functions showing up in my archived email. And the drop at the end reflects the fact that one doesn’t yet know future Mathematica names. But it’s interesting to see elsewhere in the plot little “bursts of creativity”, mostly but not always correlated with important moments in Mathematica history—as well as a general increase in density in recent times.

As a quite different measure of creative progress, here’s a plot of when I modified the text of chapters in A New Kind of Science:

I don’t have data readily at hand from the beginning of the project. And in 1995 and 1996 I continued to do research, but stopped editing text, because I was pulled away to finish Mathematica 3 (and the book about it). But otherwise one sees inexorable progress, as I systematically worked out each chapter and each area of the science. One can see the time it took to write each chapter (Chapter 12 on the Principle of Computational Equivalence took longest, at almost 2 years), and which chapters led to changes in which others. And with enough effort, one could drill down to find out when each discovery was made (it’s easier with modern Mathematica automatic history recording). But in the end—over the course of a decade—from all those individual keystrokes and file modifications there gradually emerged the finished A New Kind of Science.

It’s amazing how much it’s possible to figure out by analyzing the various kinds of data I’ve kept. And in fact, there are many additional kinds of data I haven’t even touched on in this post. I’ve also got years of curated medical test data (as well as my not-yet-very-useful complete genome), GPS location tracks, room-by-room motion sensor data, endless corporate records—and much much more.

And as I think about it all, I suppose my greatest regret is that I did not start collecting more data earlier. I have some backups of my computer filesystems going back to 1980. And if I look at the 1.7 million files in my current filesystem, there’s a kind of archeology one can do, looking at files that haven’t been modified for a long time (the earliest is dated June 29, 1980).

Here’s a plot of the latest modification times of all my current files:

The colors represent different file types. In the early years, there’s a mixture of plain text files (blue dots) and C language files (green). But gradually there’s a transition to Mathematica files (red)—with a burst of page layout files (orange) from when I was finishing A New Kind of Science. And once again the whole plot is a kind of engram—now of more than 30 years of my computing activities.

So what about things that were never on a computer? It so happens that years ago I also started keeping paper documents, pretty much on the theory that it was easier just to keep everything than to worry about what specifically was worth keeping. And now I’ve got about 230,000 pages of my paper documents scanned, and when possible OCR’ed. And as just one example of the kind of analysis one can do, here’s a plot of the frequency with which different 4-digit “date-like sequences” occur in all these documents:

Of course, not all these 4-digit sequences refer to dates (especially for example “2000”)—but many of them do. And from the plot one can see the rather sudden turnaround in my use of paper in 1984—when I turned the corner to digital storage.

What is the future for personal analytics? There is so much that can be done. Some of it will focus on large-scale trends, some of it on identifying specific events or anomalies, and some of it on extracting “stories” from personal data.

And in time I’m looking forward to being able to ask Wolfram|Alpha all sorts of things about my life and times—and have it immediately generate reports about them. Not only being able to act as an adjunct to my personal memory, but also to be able to do automatic computational history—explaining how and why things happened—and then making projections and predictions.

As personal analytics develops, it’s going to give us a whole new dimension to experiencing our lives. At first it all may seem quite nerdy (and certainly as I glance back at this blog post there’s a risk of that). But it won’t be long before it’s clear how incredibly useful it all is—and everyone will be doing it, and wondering how they could have ever gotten by before. And wishing they had started sooner, and hadn’t “lost” their earlier years.

Comment added April 5:

Thanks for all the great comments and suggestions, both here and in separate messages!

I’d like to respond to a few common questions that have been asked:

How can I do the same kind of analysis you did?

Eventually I hope the answer will be very simple: just upload your data to Wolfram|Alpha Pro, and it’ll all be automatic. But for now, you can do it using Mathematica programs. We just posted a blog explaining part of the analysis, and linking to the source for the Mathematica programs that you’ll need. To use them, of course, you’ll still have to get your data into some kind of readable form.

What systems did you use to collect all the data?

Different ones at different times, and on different computer systems. For keystroke data, for example, I used several different keyloggers—mostly rather shadowy pieces of software marketed primarily for surreptitious uses. For the phone call data, all my landline phones have always been connected to our company phone system (originally a PBX, now a VoIP system), so I was able to use its built-in logging capabilities. For email, I had a script set up as part of our company email system back in 1989 that forks off a copy of all my messages, and sends them to an archive. This script has had to be updated quite a few times over the years when we’ve changed email systems.

How does your treadmill setup work?

It’s pretty straightforward. I have a keyboard mounted on a board that attaches to the two side rails of the treadmill. I’ve carefully adjusted the height of the keyboard, and I’ve put a gel strip in front of it, to rest my wrists on. I have the mouse on a little platform at the side of the treadmill. And I have two displays mounted in front of me. I’ve sometimes thought about developing some kind of kit to let other people “computerize” their treadmills… but it’s seemed too far from my usual business. (And when I first had the treadmill set up, I was still a bit embarrassed about my impending middle age, and need for exercise.)

With everything you have going on, do you find time for your family?

Happily, very much so. It’s helped a great deal that I’ve always worked at home, so when I’m not actively in the middle of working, I can spend time with my family. It’s also helped that I’ve been very consistent for a long time in taking an extended dinner break with my family (that’s the 2.5 hour gap visible in the early evening in most of my plots). In the blog, I concentrated on work-related personal analytics; I have quite a lot more that’s family oriented, but I didn’t include this in the blog.