The Wolfram Institute recently received a grant from the Templeton World Charity Foundation for “Computational Metaphysics”. I wrote this piece in part as a launching point for discussions with experts in traditional philosophy.

Moving Metaphysics from Philosophy to Science

“What ultimately is there?” has always been seen as a fundamental—if thorny—question for philosophy, or perhaps theology. But despite a couple of millennia of discussion, I think it’s fair to say that only modest progress has been made with it. But maybe, just maybe, this is the moment where that’s going to change—and on the basis of surprising new ideas and new results from our latest efforts in science, it’s finally going to be possible to make real progress, and in the end to build what amounts to a formal, scientific approach to metaphysics.

It all centers around the ultimate foundational construct that I call the ruliad—and how observers like us, embedded within it, must perceive it. And it’s a story of how—for observers like us—fundamental concepts like space, time, mathematics, laws of nature, and indeed, objective reality, must inevitably emerge.

Traditional philosophical thinking about metaphysical questions has often become polarized into strongly opposing views. But one of the remarkable things we’ll see here is that with what we learn from science we’ll often be able to bring together these opposing views—typically in rather unexpected ways.

I should emphasize that my goal here is to summarize what we can now say about metaphysics on the basis of our recent progress in science. It’ll be very valuable to connect this to historical positions and historical thinking in philosophy and theology—but that’s not something I’m going to attempt to do here. I should also say that I’m going to concentrate on the major intellectual arc of what one can think of as a new scientific approach to metaphysics; the technical details of the science I’ve mostly already discussed elsewhere.

The Foundations of Physics

We’re going to begin our journey by talking about the traditional objective of physics: to find abstract theories that describe what we observe and measure in the physical world. From the history of physics we’ve come to expect that such theories will always end up being at best successive approximations. But the new possibility raised by our Physics Project is that we may now finally have reached the end: a truly fundamental theory of physics, that provides a complete description of the lowest-level “machine code” of our universe.

Already in antiquity the question arose of whether the universe is ultimately a continuum or is made of discrete atomic elements. By the end of the nineteenth century it was finally established that matter, at least, consists of discrete elements. And soon it became clear that light could be thought of in the same way. But what about space? Ever since Euclid, it had been assumed that space was a continuum. And efforts in the early twentieth century to see whether it, like matter, might be discrete did not work out.

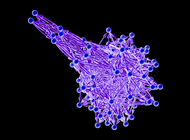

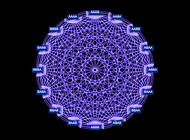

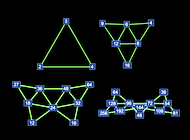

But a century later, building on new, computationally inspired ideas, our Physics Project starts from the concept that space is not just a simple continuum. Instead, it’s a complicated discrete structure that in fact represents every aspect of our universe—both what we normally think of as space, and everything in it. There are many ways one can imagine describing this structure. A convenient one is to say that it consists of a very large number of discrete intrinsically identical “atoms of space”—that one can think of as being like disembodied geometrical points—whose only property (other than being distinct) is how they’re abstractly related to other atoms of space. In other words, we imagine describing the whole structure of the universe in terms of the pattern of relations between the atoms of space. And it’s convenient to represent this as a hypergraph whose nodes are atoms of space, and whose hyperedges define the relations between them. (If relations are only between pairs of nodes, this becomes an ordinary graph.)

An important piece of intuition that comes from our practical experience with computers is that it’s possible to represent everything we deal with in terms of bits. But when we also want to represent the structure of space it’s better to think not in terms of bits in some predetermined arrangement, but instead in terms of the lower level and more flexible “data structure” defined by a hypergraph.

So how can the universe as we normally perceive it emerge from this? It’s very much analogous to what happens with matter. For example, even though something like water consists of discrete molecules, the aggregate effect of them is to produce seemingly continuous fluid behavior. But then—still made up of the same underlying molecules—we can have discrete eddies in the fluid, analogous in the case of space to particles like electrons (or, for that matter, black holes).

Time and Spacetime

If there’s a hypergraph that’s the ultimate “data structure” of the universe, what are the algorithms that get applied to it? Just as we imagine the data structure to consist of discrete elements, so also we imagine that changes to it occur by discrete events. And for now we can imagine that there’s some fixed rule that determines these elementary events. For example, the rule might be that whenever a piece of the hypergraph has some specified form, it should be replaced by a piece of hypergraph with some other specified form.

We can think of the application of such a rule as corresponding to the computation of the “next state” of the universe from the previous one. And if the rule is repeatedly applied, it will generate a whole sequence of updated states of the universe. And we can then identify the progression of these states as corresponding to the progression of time in the universe.

It’s notable that in this setup space and time are, at least at the outset, different kinds of things. Space is associated with the structure of the hypergraph, yet time is associated with computation on it.

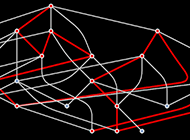

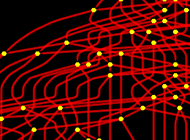

Still, just as the hypergraph defines relations between atoms of space, we can imagine a causal graph that defines “causal relations” between events. Any particular event can be thought of as taking some collection of atoms of space as “inputs”, and producing some other collection of atoms of space as “outputs”. But this then implies a causal relation between events: any event that uses as input an atom of space that was generated as output by another event can be thought of as “causally dependent” on that other event.

And the whole pattern of these causal relations ultimately defines a causal graph for all events in the universe—that in a sense encodes the structure of the universe in both space and time.

But given such a causal graph, can we reconstruct a series of hypergraphs from it? We can think of such hypergraphs as representing successive “instantaneous states of space”. And—just like in relativity—it turns out that there isn’t a unique possible such sequence of states. Instead, there are many different sequences, all consistent with the underlying causal graph—and corresponding in traditional physics terms to different relativistic reference frames.

In effect, therefore, we can think of the causal graph as being the “true representation” of information about the universe. Any particular “reconstructed” sequence of hypergraphs inevitably involves arbitrary choices.

When we introduced the causal graph, we talked about building it by starting from a particular hypergraph, and then looking at the effect of applying rules to it. But the point is that it turns out there’s a lot of choice in both the hypergraph and how we apply the rules, but (as a result of the phenomenon of causal invariance) essentially all choices will lead us to the same causal graph.

We might have imagined that given a fundamental theory of physics we should be able to ask what the universe in some sense “statically is”. But what we’re discovering is that we should instead be talking about the processes that happen in the universe—as represented by the causal graph.

We can identify the passage of time as the progression of events in the causal graph. But why is there even something like space? Ultimately it turns out to be a reflection of the “entanglement” of different sequences of events in the causal graph—and its structure is in effect a map of the relations between these sequences of events (a structure which can conveniently be represented by a hypergraph).

Imagine starting from one event in the causal graph, then tracing a sequence of events that depend on it. We can think of the successive events as occurring progressively later in time. But what about two events that are both immediate successors of a given event? What is their relationship? The key idea is that even though these “sibling” events occur “at the same time”, they are still separated—in what we can think of as space.

But how then is “space as a whole” formed? Ultimately it’s something very dynamic. And indeed it’s the continual occurrence of events in the universe that “knits together” the structure of space. Without such “activity”, there would be nothing we could coherently consider as “space”.

At the level of atoms of space there is nothing permanent in the universe; in every elementary event, atoms of space are destroyed, and new ones created. But somehow at an aggregate level there is a certain stability to what emerges. It’s again a little like with fluids, where the microscopic motions of huge numbers of underlying molecules lead in the aggregate to the laws of fluid mechanics.

But what then are the aggregate laws that emerge from large numbers of hypergraph updates? Remarkably enough, they almost inevitably turn out to be exactly the Einstein equations: the equations that seem to govern the large-scale structure of spacetime. So even though what’s “there underneath” is just what we might think of as “abstract” atoms of space and rules for rewriting relations between them, what emerges is something that reproduces familiar elements of what we think of as “physical reality”.

The Phenomenon of Computational Irreducibility

If there’s a rule that can ultimately reproduce the behavior of the universe, how complicated a rule does that need to be? Our traditional intuition—say from experience from engineering—is that one needs a complicated rule if one wants to produce complicated behavior. But my big discovery from the early 1980s is that this isn’t the case—and that in fact it’s perfectly possible even for extremely simple underlying rules (like my favorite “rule 30”) to produce behavior of immense complexity.

But why ultimately does this happen? We can think of running a rule as being like running a program, or, in other words, like doing a computation. But how sophisticated is that computation? We might have thought that different rules would do incomparably different computations. But the existence of universal computation—discovered a century ago—implies that in fact there’s a class of universal rules that can effectively emulate any other rule (and this is why, for example, software is possible).

But actually there’s a lot more that can be said. And in particular my Principle of Computational Equivalence implies that essentially whenever one sees a system whose behavior is not obviously simple, the system will actually be doing a computation that is in some sense as sophisticated as it can be. In other words, sophisticated computation isn’t just a feature of specially set up “computer-like” systems; it’s ubiquitous, even among systems with simple underlying rules.

So what does this mean? It’s often considered a goal of science to be able to predict what systems will do. But to make such a prediction requires in a sense being able to “jump ahead” of the behavior of the system itself. But the Principle of Computational Equivalence tells us that this won’t in general be possible—because it’s ubiquitous for the system we’re trying to predict to be just as computationally sophisticated as the system we’re trying to use to predict it. And the result of this is the phenomenon of computational irreducibility.

You can always find out what a system will do just by explicitly running its rules step by step. But if the system is computationally irreducible there’ll be no general way to shortcut this, and to find the result with reduced computational effort.

Computational irreducibility is what irreducibly separates underlying rules from the behavior they produce. And it’s what causes even simple rules to be able to generate behavior that cannot be “decoded” except by irreducibly great computational effort—and therefore will be considered random by an observer with bounded computational capabilities.

Computational irreducibility is also what in a sense makes time something “real”. We discussed above that the passage of time corresponds to the progressive application of computational rules. Computational irreducibility is what makes that process “add up to something”. And the Principle of Computational Equivalence is what tells us that there’s something we can think of as time that is in effect “pure, irreducible computation” independent of the system in which we’re studying it.

It’s very much the same story with space. Computational irreducibility in general leads to a certain “uniform effective randomness” in the structure of hypergraphs, which is what allows us to imagine that there’s a definite “substrate independent” concept of space.

There’s a close analogy here to what happens in something like a fluid. At a molecular level there are lots of molecular collisions going on. But the point is that this is a computationally irreducible process—whose end result is enough “uniform effective randomness” that we can meaningfully talk about the properties of the fluid “in bulk”, as a thing in itself, without having to mention that it’s made of molecules.

So how does all this relate to our original metaphysical question of what there ultimately is? Computational irreducibility introduces the idea that there’s something robust and invariant about “pure computation”—something that doesn’t depend on the details of what’s “implementing” that computation. Or, in other words, that there’s a sense in which it’s meaningful to talk about things simply being “made of computation”.

The Significance of the Observer

In talking about things like a hypergraph representing space and everything in it, we’re giving in a sense an objective description of the universe “from the outside”. But what ultimately matters to us is not what’s “in principle out there”, but rather what we actually perceive. And indeed we can think of science as being first and foremost a way to find narrative descriptions which fit in our minds of certain aspects of what’s out there.

But given computational irreducibility, why is this even possible? Why are there ever, for example, “laws of nature” which let us make predictions about things, even with the bounded amount of computation that our finite minds can do?

The answer is related to an inevitable and fundamental feature of computational irreducibility: that within any computationally irreducible process there must always be an infinite number of pockets of computational reducibility. In other words, even though computational irreducibility makes it irreducibly difficult to say everything about what a system will do, there will always be pockets of reducibility which allow one to say certain things about it. And it’s such pockets of reducibility that our processes of perception—and our science—make use of.

Once again we can use fluid dynamics as an example. Even though the detailed pattern of underlying molecular motions in a fluid is computationally irreducible, there are still computationally simple overall laws of fluid flow—that we can think of as being associated with pockets of computational reducibility. And from our point of view as computationally bounded observers, we tend to think of these as the laws of the fluid.

In other words, the laws we attribute to a system depend on our capabilities as observers. Consider the Second Law of thermodynamics, and imagine starting from some simple configuration, say of gas molecules. The dynamics of these molecules will generically correspond to a computationally irreducible process—whose outcome to a computationally bounded observer like us will seem “increasingly random”. Of course, if we were not computationally bounded, then we’d be able to “decode” the whole underlying computationally irreducible process, and we wouldn’t believe in the presence of seemingly increasing randomness, or, for that matter, the Second Law. But—regardless of any details—as soon as we’re computationally bounded, we’ll immediately perceive the Second Law.

We might have assumed that the Second Law was some kind of intrinsic law of nature—directly related to what there ultimately is. But what we see is that the Second Law is something that emerges because of us, and our characteristics as observers, and in particular our computational boundedness.

There are other things that also work this way—for example, our belief in a coherent notion of space. At the lowest level we imagine that there’s a discrete hypergraph being updated through what’s ultimately a computationally irreducible process. But as computationally bounded observers we only perceive certain aggregate features—that correspond in effect to a pocket of computational reducibility associated with our simple, continuous perception of space.

When we think about spacetime—and for example about deriving its relativistic properties—there’s another feature of us as observers that also turns out to be important: the fact that we assume that we are persistent in time, and that—even though we might be made of different atoms of space at every successive moment of time—we can still successfully knit together perceptions at successive moments of time to form a single thread of experience. In a sense this is a “simplification” forced upon us by our computational boundedness. But it’s also in many ways at the core of what we think of as our notion of consciousness (which is something I’ve written about at some length elsewhere).

The Principle of Computational Equivalence implies that sophisticated computation is ubiquitous—and certainly not something special to brains. And indeed it seems that brains actually concentrate on a specific—and in many ways limited—form of computation. They take in large amounts of sensory data, and in effect compress it to derive what’s ultimately a thin stream of actions for us to take. At a biological level, there’s always all sorts of activity going on across the billions of neurons in our brains. But our brains are, it seems, specially constructed to concentrate all that activity down to what’s essentially a single thread of thought, action and “experience”. And it’s the fact that this is a single thread that seems to give us our sense of coherent existence, and in effect, of consciousness.

Quantum Mechanics and Multiway Systems

Traditional classical physics talks about definite things happening in the universe—say a projectile following a definite path, determined by its laws of motion. But quantum mechanics instead talks about many paths being followed—specifying only probabilities for their various outcomes.

In this history of physics quantum mechanics was a kind of “add on”. But in our Physics Project it’s immediately essential, and unavoidable. Because the rules that we define simply say that whenever there is a piece of a hypergraph that matches a particular pattern, it should be transformed. But in general there will be many such matches—each one producing a different transformation, and each one in effect initiating what we can think of as a different path of history. And in addition to such branching, there can also be merging—when different transformations end up producing the same hypergraph.

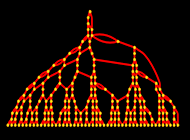

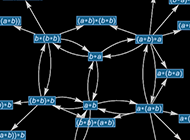

We can represent all these branching and merging paths of history by what I call a multiway graph. And we can think of such a multiway graph as giving a complete description of “what happens” in the universe.

But as we discussed above, observers like us maintain just a single thread of experience. And that means we can’t directly perceive a whole multiway graph. Instead, we have to effectively pick out just one path from it. But which path will it be? At the level of the formalism of quantum mechanics—or of our Physics Project—the only thing we talk about is the whole collection of all paths. So something else must determine the path.

In physical space, we’re used to the idea that we as observers are localized at a particular position, and only get to directly perceive what’s around where we are. Across all of physical space, there are lots of things going on. But because of where we happen to be, we only get to directly perceive a tiny sample of them.

So is something similar going on in picking paths of history from the multiway graph? It seems that it is. If we take a slice across the multiway graph at any particular time, we’ll have lots of “dangling ends” of paths of history, each associated with a different state of the universe. But inevitably there are lots of relations between these states. (For example, two states might have an immediate common ancestor.) And it turns out that we can think of the states as being laid out in what we can call “branchial space”.

And just like in physical space, we can expect that we as observers are localized in branchial space. So that means that even though there are at some level many different paths of history, we only get to perceive ones that are around “where we are”. And just like there’s no “theory” that tells us where we find ourselves in physical space (which planet, which galaxy, etc.), the same is true in branchial space. One day we might have some way to describe our location in branchial space, but for now the best we can do is say that it’s “random”.

And this, I believe, is why outcomes in quantum mechanics seem to us random. The whole multiway graph is completely determined (as wave functions etc. are even in the standard formalism of quantum mechanics). But which part of the multiway graph we as observers sample depends on where we are in branchial space.

And we can expect that just as we humans are all close together in physical space, so are we in branchial space. And this means that even though in the abstract the result of, say, some particular quantum measurement might seem “random”, all human observers—being nearby in branchial space—will tend to agree what that result is, and at least among them, there’ll be something they can consider “objective reality”.

The Concept of the Ruliad

The remarkable implication of our Physics Project is that our whole universe, in all its richness, can emerge just from the repeated application of a simple underlying rule. But which rule? How would it be selected?

The idea of the ruliad is to imagine that no selection is needed—because all rules are being used. And the ruliad is what comes out: the entangled limit of all possible computational processes.

We discussed in the context of quantum mechanics the idea that a given rule can get applied in multiple ways, leading to multiple paths of history. The ruliad takes this idea to the limit, applying not just one rule in all possible ways, but all possible rules in all possible ways.

We can imagine representing the ruliad by a giant multiway graph—in which there is a path that represents any conceivable specific computation. And what fundamentally gives the ruliad structure is that these paths can not only branch but also merge—with mergers happening when different states lead to equivalent outcomes which are merged in the multiway graph.

At first we can think of the ruliad as being built from all possible hypergraph rules in our Physics Project. But the Principle of Computational Equivalence implies that actually we can use any type of rule as our basis: since the ruliad contains all possible computational processes its final form will be the same.

In other words, however we end up representing it, the intrinsic form of the ruliad is still the same. Once we have the concept of computation (or of following rules), the ruliad is an inevitable consequence. In some sense it is the ultimate closure of the concept of computation: the unique object that encapsulates all possible computational processes and the inevitable relations between them.

We got to the ruliad by thinking about physics, and about the ultimate infrastructure of our physical universe. But the ruliad is something much more general than that. It’s an abstract object that captures everything that is computationally formalizable, along with the elaborate structure of relations between such things.

Of course, the idea that the ruliad can describe our actual physical universe is ultimately just a hypothesis—though one that’s strongly encouraged by the success of our Physics Project.

How could it be wrong? Well, our universe could involve hypercomputation—which is not finitely captured by the ruliad. And we might have to consider a whole hierarchy of possible hyperruliads. (Though as we’ll see, any effects from this would likely be beyond anything observers like us could perceive.)

But assuming that the ruliad is the ultimate infrastructure for everything we can then ask what it’s made of. At some level we could just say it’s made of abstract computational processes. But what are those processes operating on? Again, abstract things. But we can imagine decomposing those abstract things. And while inevitably there will be different ways to do this, it’ll often be convenient to imagine that they consist of relations between ultimate, indivisible objects—which we can describe as “atoms of existence”, or what I’ve called “emes”.

In our Physics Project, we identified emes with atoms of space. But in talking about the ruliad in general, we can think of them just as the “ultimate raw material for existence”. Emes have no structure of their own. And indeed the only intrinsic thing one can say about them is that they are distinct: in a sense they are elementary units of identity. And we can then think of it being the relations between them that build up the ruliad—and everything it underlies.

Observers in the Ruliad and the Laws of Nature

Our original metaphysical question was: “What ultimately is there?” And at some level our science has now led us to an answer: the ruliad is everything there ultimately is.

But what about what there is for us? In other words, what about what there ultimately is in what we perceive and experience? Inevitably, we as observers must be part of the ruliad. And our “inner experiences” must similarly be represented within the ruliad. But in and of itself that’s not enough to tell us much about what those experiences might be. And we might imagine that to work this out, we’d need to know a lot of the particular details of our construction, and our place in the ruliad.

But what’s emerged in the last few years is that in many important ways, we don’t. And instead just knowing certain coarse features of us as observers already implies a lot about what we must experience. In particular, if we assume that we are observers who are computationally bounded, and believe we are persistent in time, then we argue that it is inevitable that we must perceive certain laws to be operating—and those laws turn out to be exactly the three central laws of twentieth century physics: general relativity, quantum mechanics, and the Second Law of thermodynamics.

It’s a remarkable claim: the laws of physics we observe don’t just happen to be the way they are; they are inevitable for observers with the general characteristics we have. At the level of the underlying ruliad the laws of physics that we might observe are not determined. But as soon as we know something about what we’re like as observers, then we necessarily end up with our familiar laws of physics.

In a sense, therefore, the laws of physics that we experience are the way they are because we are observers that are the way we are. We already discussed this above in the case of the Second Law. And although we don’t yet know all the details, the basic conclusion is that by combining the abstract structure of the ruliad with our assumptions about what we’re like as observers, we are able to derive all three of the familiar core laws of physics from the twentieth century.

It’s worth emphasizing that what we can immediately derive are in a sense “general laws”. We know that spacetime has a certain overall structure, and its dynamics satisfy the Einstein equations. But we don’t, for example, know why the universe as we perceive it has (at least approximately) 3 dimensions of space—though my guess is that many such features of observed physics can ultimately be traced to features of the way we are as observers.

So what about observers not like us? They’re still part of the ruliad. But in a sense they’re sampling it in a different way. And they’ll potentially perceive quite different laws of physics.

It’s a very fundamental observation about our universe that we perceive it to follow fairly simple laws. But in a sense this too is just a feature of our nature as observers. Because given our computational boundedness we couldn’t really make use of—or even identify—any laws that were not in some sense simple.

The fact that simple laws are possible can be viewed as a reflection of the inevitable presence of pockets of computational reducibility within any computationally irreducible process. But it’s our computational boundedness as observers that causes us to pick them out. If we were not computationally bounded then we could operate at the level of raw computational irreducibility, and any need to pick out simple laws.

At the outset, we might have imagined that the laws of physics would somehow fundamentally be at the root of the question of “what ultimately is there?” But what we’re seeing is that actually these laws are in a sense higher-level constructs, whose form depends on our characteristics as observers. And to get to our original metaphysical question, we have to “drill down” beyond our perceived laws of physics to their “computational infrastructure”, and ultimately all the way to the ruliad.

The Question of Objective Reality

When we ask what there ultimately is, we’re in some sense implicitly assuming that there actually is something definite—or in effect that there’s a single ultimate “objective reality”. But is that actually how things work, or does every observer, for example, in effect “have their own reality”?

In our approach, there’s a quite nuanced answer. At the very lowest level there is a single ultimate objective reality that knits everything together—and it’s the ruliad. But meanwhile, different observers can in principle experience different things. But as soon as we’re dealing with observers even vaguely like us (in the sense that they share our computational boundedness, and our belief in our own persistence) we’ve argued that it’s inevitable that they’ll always experience the core laws of physics as we know them. In other words, these laws in effect represent a single objective reality—at least across observers even vaguely like us.

But what about more detailed features of our experience? No doubt some we’ll be able to “objectively derive” on the basis of characteristics we identify as shared across all “observers like us”. But at some level, different observers will always have different experiences—not least because, for example, they are typically operating at different places in space, and indeed in general at different places in the ruliad.

Still, our everyday impression is that even though the detailed experiences, say, of different people looking at the same scene may be different, those experiences can nevertheless reasonably be thought of as all derived from the same “underlying objective reality”. So why is this? Essentially I think it’s because human observers are all very nearby in the ruliad—so they’re in a sense all sampling the same tiny part of the ruliad.

Observers at different places in the ruliad in effect sample different threads of history, that operate according to different rules. But the Principle of Computational Equivalence tells us that—just as it’s always possible to translate from one universal computational system to another—it’ll always in the end be possible to translate between what observers get by sampling at different places in the ruliad.

The difficulty of translation depends, though, on how far one is trying to go in the ruliad. Human minds exposed to similar knowledge, culture, etc. are nearby and fairly easy to translate between. Animal minds are further away, and more difficult to translate to. And when it comes to something like the weather, then even though in principle it’s computationally equivalent, the distance one has to go in the ruliad to reach it is sufficiently great that translation is very difficult.

Translation between places in the ruliad is in a sense just a generalization of translation in physical space. And the process of moving in physical space is what we describe as motion. But what actually is motion? In effect it’s having something move to a different place in space while still “being the same thing”. In our Physics Project, though, something must be made of different atoms of space if it’s at a different place in space. But somehow there must be some pattern of atoms of space that—a bit like an eddy in a fluid—one can say represents “the same thing” at different places in space.

And potentially one can think of particles—like electrons or photons—as being in a sense “elementary carriers of pure motion”: minimal objects that can move without changing.

But how does this work more generally in the ruliad? What is it that can “move” between observers, or between minds, without changing? Essentially it seems to be concepts (often in basic form represented by words). Within for example one human brain a thought corresponds to some complicated pattern of neural activity. But what allows it to be “moved” to another brain is “packaging it up” into a “concept” that can be unpacked by another brain. And at some level it’s this kind of communication that “aligns observers” to have similar inner experiences—to the point where they can be viewed as reflecting a common objective reality.

But all of this somehow presupposes that there are many observers—whose experiences can be thought of as “triangulating” to a common objective reality. If there were just one observer, though, there’s no triangulation to do, and one might imagine that all that would matter is the inner experience of that one observer.

So in a sense the very notion that we can usefully talk about objective reality is a consequence of there being many similar observers. And of course in the specific case of us humans there are indeed billions of us.

But from a fundamental point of view, why should there be many similar observers, or even any observers at all? As we discussed above, the core abstract characteristic of an observer is its ability to equivalence many possible inputs to produce a small set of possible outputs. And—although we don’t yet know how to do it—we can imagine that it would be possible to derive the fact that there must be a certain density of structures that do this within the ruliad. Could there inevitably be enough similar observers to be able to reasonably triangulate to an objective reality?

If we take the example of biology (or modern technology) it seems like what’s critical in generating large numbers of similar observers is some form of replication. And so, surprising as it might seem for something as apparently fundamental as this, it appears that our impression of the existence of objective reality is actually intimately tied up with the rather practical biological phenomenon of self replication.

OK, so what should we in the end think about objective reality? We might have imagined that having a scientific theory of the universe would immediately imply a certain objective reality. And indeed at the level of the ruliad that’s true. But what we’ve seen is that even to get our familiar laws of physics we need an observer “parsing” the raw ruliad. In other words, without the observer we can’t even talk about fundamental concepts in physics. But the point is that for a very wide range of observers even vaguely like us, many details of the observer don’t matter; certain things—like core laws of physics—inevitably and “objectively” emerge.

But the laws of physics don’t determine everything an observer perceives. Some things are inevitably determined by the particular circumstances of the observer: their position in space, in the ruliad, etc. But now the point is that observers—like us humans—are nearby enough in space, the ruliad, etc. that our perceptions will be to a large extent aligned, so that we can again usefully attribute them to what we can think of as an external objective reality.

The Beginning and End of Time

In thinking about what there ultimately is, an obvious question is whether whatever there is has always been there—and will always be—or whether instead there’s in effect a beginning—and end—to time.

As we discussed above, in our computational paradigm, the passage of time is associated with the progressive computation of successive states of the universe. But the important point is that these states embody everything—including any potential observers. So there can never be a situation where an observer could say “the universe hasn’t started yet”—because if the universe hasn’t started, nor will the observer have.

But why does the universe start at all? We’ll say more about that later. But suffice it to say here that the ruliad in effect contains all possible abstract computations, each consisting of some chain of steps that follow from each other. There’s nothing that has to “actively start” these chains: they are just abstract constructs that inevitably follow from the definition of the ruliad.

There’ll be a beginning to each chain, though. But the ruliad contains all possible beginnings, or in other words, all possible initial states for computations. One might wonder, given all of this, how the ruliad can still have any kind of coherent structure. The answer, as we discussed above, is the entanglement of different threads of computation: the threads are not independent, but are related by the merging of equivalent states.

Of course one can then ask why equivalent states are in fact merged. And this is immediately a story about observers. One can imagine a raw construction of the ruliad in which every different thread of computation independently branches. But anytime states generated in different threads are identical, any observer will equivalence them. So this means that to any observer, these threads will be merged—and there will effectively be entanglement in the ruliad.

We’ve said that the passage of time corresponds to the progression of computation. And given this, we can imagine that the ruliad is built up “through time”, by progressively applying appropriate rules. But actually we don’t need to think of it this way. Because once a procedure for the construction of the ruliad is defined, it’s inevitable that the whole structure of the ruliad is, at least in principle, immediately determined.

In other words, we can imagine building up the ruliad step by step through time. Or we can imagine that the ruliad in some sense all immediately “just exists”. But the point is that to computationally bounded observers these are basically equivalent. In the first case the observer is “pulled along” by the irreducible computation that’s “happening anyway” to move forward the “frontier” of the ruliad. In the second case, the observer in a sense has to actively explore the “already-formed” ruliad, but because of the observer’s computational boundedness, can do so only at a certain limited rate—so that once again there is something corresponding to the passage of time, and relating it to computational irreducibility.

But what happens if one includes the fact that there are threads of computation in the ruliad starting from all possible initial states? Well, a bounded observer will only be able to probe all these states and their behaviors at some limited rate. So even if “from outside the ruliad” (if one could be there) one might see infinitely many different beginnings of the universe, any computationally bounded observer embedded in the ruliad would perceive only a limited set. And, indeed, depending a bit on the scales involved, the observer might well be able to conflate those limited possibilities into the perception of just a single, finite beginning of the universe—even though, underneath, there’s much more going on in the whole ruliad.

(One thing one might wonder is that since the ruliad contains every possible rule, why can’t there just be a single, very complicated rule that just creates our whole universe in a single step? The answer is that in principle there can be. But computationally bounded observers like us will never perceive it; our “narrative about the universe” might involve computationally limited steps.)

Another subtlety concerns the relationship of time to the equivalencing of states. Imagine that in the ruliad (or indeed just in a causal graph) a particular state is generated repeatedly when rules are applied. We can expect an observer to equivalence these different instances of the state—thus in effect forming a loop in the progression of states. Quite possibly such loops are associated with phenomena in quantum field theory. But to an observer like us such loops will be happening at a level “below” perceived time.

We talked about the beginning of time. What about the end? If the passage of time is the progression of computation, can the computation simply halt? The answer for any specific computation is yes. A particular rule might, for example, simply not apply anywhere in a given hypergraph. And that means that in effect time stops for that hypergraph. And indeed this is what presumably happens at the center of a black hole (at least in the simplest case).

But what about the whole ruliad? Inevitably parts of it will “keep running”, even if some threads of computation in it stop. But the question is what an observer will perceive of that.

Normally we’ve just taken it for granted that an observer does whatever they do forever. But in reality, as something embedded in the ruliad, an observer will at some level have to “navigate computational irreducibility” to maintain itself. And whether it’s because a biological observer dies, or because an observer ends up in a black hole, we can expect the actual span of experience of individual observers to be limited, in effect defining an end of time for the observer, even if not for the whole ruliad.

Why Does Anything Actually Exist?

In our discussion of what there ultimately is, an obvious question is why there’s ultimately anything at all. Or, more specifically, why does our universe exist? Why is there something rather than nothing?

One might have imagined that there’d be nothing one could say about such questions in the framework of science. But it turns out that in the context of the ruliad there’s actually quite a lot one can say.

The key point is that the ruliad can be thought of as a necessary, abstract object. Given a definition of its elements it inevitably has the structure it has. There’s no choice about it. It’s like in mathematics: given the definitions of 1, +, etc.,

And so it is with the ruliad. The ruliad has to be the way it is. Every detail of it is abstractly determined. Or, in other words, at least as an abstract object, it necessarily exists.

But why, we might ask, is it actualized? We can imagine all sorts of formal systems with all sorts of structure. But why is the ruliad what is actualized to give us the physical world we experience?

The key here is to think about what we operationally mean by actualized. And the point is that it’s not something absolute; it’s something that depends on us as observers. After all, the only thing we can ever ultimately know about is our own inner experience. And for us something is then “actualized” if we can—as we discussed above—successfully “triangulate our experiences” to let us consider it to have an objective reality.

At some level, the ruliad is an abstract thing. And our inner experiences are abstract things. And we’re saying that there’s a certain abstract necessity to the way these things are linked. With what amounts to a description of our physical world being a necessary intermediate step in that linking.

Given its definition, it’s immediately inevitable that the ruliad must exist as an abstract object. But what about observers like us? We know ourselves that we exist from the inner experiences we have. But is it necessary that we exist? Or, put another way, is it inevitable that somewhere in the ruliad there must be structures that correspond to observers like us?

Well, that’s a question we can now study as a matter of science. And ultimately we can imagine an abstract derivation of the density of different levels of observers in the ruliad. To get to observers like us requires—as we discussed above—all sorts of details, probably including features from biology, like self replication. But if we require only the features of computational boundedness and a belief in persistence, there are no doubt many more “observer structures” in the ruliad.

It’s interesting to consider those “alien minds” distributed across the ruliad. In traditional searches for extraterrestrial intelligence one is seeking to bridge distances in physical space. But likely the distances across the ruliad—in rulial space—are vastly greater. And in effect the “minds” are more alien (like the “mind” of the weather)—and to “communicate” with them will require, in effect, an effort of translation that involves an immense amount of irreducible computation.

But for us, and our science, what matters is our own experience. And given our knowledge that we exist, the existence of the ruliad seems to make it in effect inevitable that we must consider the universe to exist.

One wrinkle to mention concerns generalizations of the ruliad. We’ve said that the ruliad encapsulates all possible computational processes. But by this we mean processes that can be implemented on one of our traditional models of computation—like Turing machines. But what about hypercomputations that would require an infinite number of steps for a Turing machine? One can imagine a whole hierarchy of hyperruliads based on these. And one could imagine observers embedded not in the ordinary ruliad, but in some hyperruliad. So what would be the experience of such observers? They’d never be able to perceive anything outside their hyperruliad, and in fact one can expect that through their own hypercomputations their perception of their own hyperruliad would be essentially equivalent to our perception of the ordinary ruliad—so that in the end there’s no perceptible distinction between being in the ruliad and in a hyperruliad: the “same universe”, with the same laws of physics we know, exists in both.

When one starts talking about the universe operating at the lowest level according to computational rules people sometimes seem to think that means our universe must ultimately be “running on a computer”. But to imagine that is essentially to misunderstand the whole concept of theoretical science. For the idea in theoretical science is to construct abstract models that allow one to reproduce certain aspects of what systems do. It’s not that the systems themselves mechanistically implement the models; it’s just that the models abstractly reproduce aspects of what the systems do.

And so it is with our model for physics. It’s not that somewhere “inside the universe” there’s a computer moving bits around to rearrange hypergraphs. Instead, it’s just that abstractly rearranging hypergraphs is a way (and, no doubt, not the only one) of representing what’s happening in the universe.

Typically the models one makes in science only aim to be approximate: they capture certain aspects one cares about in a system, and idealize away all others. But our Physics Project is different, because its goal is to make a model that—at least in principle—can reproduce in perfect detail what happens in the universe, without approximation or idealization. But what we have is still just a model: in effect, a way of making a bridge from what actually happens in the universe to what we can describe in essentially human terms.

There’s a little more subtlety when it comes to the whole ruliad. Because while the ruliad is precise and complete, the sampling of it that determines what we experience depends on our characteristics as observers, about which we’ll never be able to be completely precise. And what’s more, as we’ve discussed, while the ruliad is defined in an abstract way, it is what is in effect actualized for observers like us—to provide our physics and what we consider to be our objective reality.

But could all of that somehow still be a “simulation” running on some lower-level infrastructure? Not in any meaningful sense. In talking about “simulation” we’re implicitly imagining that, in effect, the ruliad is running in one place, and other things are running elsewhere. But the ruliad encapsulates the totality of all computational processes. So in a sense there’s no room for anything outside the ruliad—and the only thing the ruliad can “run on” is itself.

Still, when it comes to observers like us, we sample only some tiny part of the ruliad—and in some sense there’s a choice about what part that is. Indeed, insofar as we view ourselves as having free will and choosing freely what observations to make (and perhaps what our own structure should be), we are in control of that choice. Our basic nature as observers will nevertheless determine some of what we experience—most notably core laws of physics. But beyond that it’s our choices as observers that effectively determine “which possible program” we’re “running” in the ruliad. So if we think of such programs as “simulations” running on the ruliad, then it’s not as if there’s some outside entity that’s picking the programs; it’s our nature and our choices that are doing it.

Mathematical Reality

We’ve talked a lot about what there ultimately is in the “concrete” physical world. But what about the “abstract” mathematical world? One of the surprising things about the ruliad is that it implies a remarkably close connection between the ultimate foundations of physics and of mathematics.

In our Physics Project we had to start by inventing a “machine-code-level” representation of the physical world in terms of hypergraphs, rewriting rules, etc. In mathematics it turns out that there’s already a well-established “machine-code-level” representation: networks of theorems stated as symbolic expressions, and transformed into each other according to (essentially structural) laws of inference.

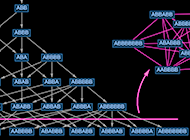

At this level of description, any particular field of mathematics can be thought of as starting from certain axioms, then building up a whole multiway graph of all possible theorems they imply. The paths in this graph correspond to proofs—with the phenomenon of undecidability manifesting itself in the presence of arbitrarily long paths—and the theorems that human mathematicians find interesting are dotted around the graph.

So what happens if instead of looking at a single axiom system we look at all possible axiom systems? What we’ll get is a structure corresponding to the entangled limit of all possible proofs—based on rules derived from all possible axiom systems. But we’ve seen an equivalent structure before: it’s just the ruliad!

But now instead of interpreting emes as atoms of space we interpret them as “atoms of mathematics”, or the lowest level elements of mathematical expressions. And instead of interpreting slices of the ruliad as corresponding in the limit to physical space, we interpret them as defining metamathematical space.

So in addition to encapsulating all possible computational processes, the ruliad also encapsulates all possible mathematical ones. But how do human mathematicians—or what we can call mathematical observers—“perceive” this? How do they extract what they consider meaningful mathematics?

Physical observers get their “view of the world” in essence by building up a thread of experience through time. Mathematical observers get their “view of the world” by starting with some set of theorems (or axioms) they choose to assume, then “moving outwards” to build up a larger collection of mathematical results.

The raw ruliad is full of computational irreducibility. But in both physics and mathematics the goal is in effect to find pockets of reducibility that let observers like us get summaries that we can fit in our finite minds. In physics this manifests in identifying concepts like space, and then identifying laws that must hold about them.

So what is the analog for mathematics? In principle one could operate at the level of axioms (or even below). But in doing Euclidean geometry, for example, it’s perfectly reasonable to talk in terms of the Pythagorean theorem, without always going down to the lowest level of definitions, say for real numbers. It’s very much like in physics, where for many purposes one can talk about something like the flow of a fluid, without having to worry about what’s going on at the level of molecular dynamics.

And indeed, just like in physics, the fact that mathematics is done by observers like us has immediate implications for what mathematics is like, or in effect, for the “laws of mathematics”. What are these laws? The most important is that higher-level mathematics is possible: in other words, that mathematicians can in fact successfully do mathematics at the “fluid dynamics” level, without always having to drop down to the raw “molecular dynamics” level of axioms and below.

There are other laws of mathematics one can expect. For example, the homogeneity of metamathematical space implied by the structure of the ruliad has the consequence that “pure metamathematical motion” should be possible, so that there must be “dualities” that allow one to translate from one field of mathematics to another. As another example, there should be analogs of general relativity in metamathematical space, with the analog of black holes in which “time stops” being decidable mathematical theories in which proofs “always stop” (in the sense that they are of bounded length).

But—just like for physics—we’re in a sense getting from the ruliad the mathematics we get because we are observers of the kind we are. We might have imagined that we could just invent whatever mathematics we want just by setting up an appropriate axiom system. But the point is that only some axiom systems—or in effect some slices of the ruliad—will allow observers with our characteristics to coherently do mathematics.

Our everyday experience of the physical world gives us the impression that we have a kind of “direct access” to many foundational features of physics, like the existence of space and the phenomenon of motion. But our Physics Project implies that these are not concepts that are in any sense “intrinsically there”; they are just things that emerge from the raw ruliad when you “parse” it in the kinds of ways physical observers like us do.

In mathematics it’s less obvious (at least to anyone except perhaps experienced pure mathematicians) that there’s “direct access” to anything. But in our view of mathematics here, it’s ultimately just like physics—and ultimately also rooted in the ruliad, but sampled not by physical observers but by mathematical ones.

So from this point of view there’s just as much that’s “real” underneath mathematics as there is underneath physics. The mathematics is sampled slightly differently—but we should not in any sense consider it “fundamentally more abstract”.

When we think of ourselves as entities within the ruliad, we can build up what we might consider a “fully abstract” description of how we get our “experience” of physics. And we can basically do the same for mathematics. So if we take the commonsense point of view that the physical world exists “for real”, we’re forced into the same point of view for mathematics. In other words, if we say that the physical world exists, so must we also say that in some fundamental sense, mathematics also exists.

Underneath mathematics, just like underneath physics, is the ruliad. And so, in a sense, what is ultimately there in mathematics is the same as what is ultimately there in physics. Mathematics is not something we humans “just make”; it’s something that comes from the ruliad, through our particular way of observing it, defined by our particular characteristics as observers.

Observers in the Vastness of the Ruliad

One of the things we’ve learned over the past few centuries is just how small we are compared to the universe. But now we realize that compared to the whole ruliad we’re still even vastly much smaller. We’re certainly not as small as we might be, though. And indeed at some level we’re actually quite large, being composed not just of a few atoms of space or, for that matter, emes, but an immense number.

We are in effect intermediate in scale: huge compared to emes, but tiny compared to the whole ruliad. And the fact that we as observers are at this scale is crucial to how we experience the universe and the ruliad.

We’re large enough that we can in some sense persistently exist and form solid, persistent experiences, not subject to constantly changing microscopic details. Yet we’re small enough that we can exist as coherent, independent entities in the ruliad. We’re large enough that we can have a certain amount of “inner life”; yet we’re small enough there’s also plenty of “external stimuli” impinging on us from elsewhere in the ruliad.

We’re also large enough that we can typically think in terms of continuous space, not atoms of space. And we can think in terms of continuous quantum amplitudes, not discrete multiway threads. But we’re small enough that we can have a consistent view of “where we are” in physical space and in branchial space. And all of us human observers are tightly enough packed in physical and branchial space that we basically agree about “what’s happening” around us—and this forms the basis for what we consider to be “objective reality”.

And it’s the same basic story when we think about the whole ruliad. But now “where we are” determines in effect what rules we attribute to the universe. And our scale is what makes those rules both fairly consistent and fairly definite. Some features of the universe—like the basic phenomena of general relativity and quantum mechanics—depend only on our general characteristics as observers. But others—likely like the masses of particles—depend on our “place in the ruliad”. (And, for example, we already know from traditional physics that something like the perceived mass of an electron depends on the momentum we use to probe it.)

When we ask what there ultimately is, one of the most striking things is how much there ultimately is. We don’t yet know the scale of the discreteness of space, but conceivably it’s around 10–90 meters—implying that at any given moment there might 10400 atoms of space in the universe, and about 10500 in the history of the universe so far. What about the whole ruliad? The total number of emes is exponentially larger, conceivably of order (10500)10500. It’s a huge number—but the fact that we can even guess at it gives us a sense that we can begin to think concretely about what there ultimately is.

So how does this all relate to human scales? We know that the universe is about 1080 times larger in volume than a human in physical space. And within one human at any given time there might be about 10300 atoms of space; our existence through our lives might be defined by perhaps 10400 emes. We can also guess at our extent in branchial space—and in the whole ruliad. There are huge numbers involved—that give us a sense of why we observe so much that seems so definite in the universe. In effect, it’s that we’re “big enough” that our “averaged” perceptions are very precise, yet we’re “small enough” that we’re essentially at a precise location within the ruliad.

(A remarkable feature of thinking in terms of emes and the ruliad is that we can do things like compare the “sizes” of human-scale physics and mathematics. And a rough estimate might be that all the mathematics done in human history has involved perhaps 10100 emes—vastly less than the number of emes involved in our physical existence.)

We can think of our “big but small” scale as being what allows us to be observers who can be treated as persistent in time. And it’s very much the same story for “persistence in space”. For us to be capable of “pure motion”, where we move from one place to another, and are still “persistently ourselves” we have to be large compared to the scale of emes, and tiny compared to the scale of the ruliad.

When it comes to moving in the physical universe, we know that to “actually move ourselves” (say with a spacecraft) takes time. But to imagine what it’s like to have moved is something that can be done abstractly, and quickly. And it’s the same at the level of the ruliad. To “move ourselves” in the ruliad in effect requires an explicit computational translation from one set of rules to another, which takes (typically irreducible) computational effort, and therefore time. But we can still just abstractly jump anywhere we want in the ruliad. And that is in effect what we do in ruliology—studying rules that we can, for example, just pick at random, or find by enumeration. We can discover all sorts of interesting things that way. But in a sense they’re—at least at first—alien things, not immediately connected to anything familiar to us from our normal location in the ruliad.

We see something similar in mathematics. We can start enumerating a huge network of possible theorems. But unless we can find a way to transport ourselves as mathematical observers more or less wholesale in metamathematical space, we won’t be able to contextualize most of those theorems; they’ll seem alien to us.

It’s not easy to get intuition for the “alien” things out there in the ruliad. One approach is to use generative AI, say to make pictures, and to ask what happens if the parameters of the AI are changed, in effect moving to different rules, and a different part of the ruliad. Sometimes one gets to recognizable pictures that are described by some concept, say associated with a word in human language. But in the vast majority of cases one finds oneself in “interconcept space”—in a place for which no existing human concept has yet been invented. And indeed in experiments with practical neural nets the fraction of this tiny corner of the ruliad spanned by our familiar concepts can easily be just 10–600 of the total. In other words, what we have ways to describe, say in human language, represents an absolutely tiny fraction of what there ultimately is.

But what happens if we invent more concepts? In some sense we then grow in rulial space—so that we as observers span a larger part of the ruliad. And perhaps we might see it as some kind of ultimate goal for science and for knowledge to expand ourselves throughout the ruliad.

But there’s a catch. The fact that we can view ourselves as definite, individual observers depends on us being small compared to the ruliad. If we could expand to fill the ruliad we would in some sense be everything—but we would also be nothing, and would no longer exist as coherent entities.

Developing a Science of Metaphysics

Metaphysics has historically been viewed as a branch of philosophy. But what I’ve argued here is that with our new results and new insights from science we can start to discuss metaphysics not just as philosophy but also as science—and we can begin to tell an actual scientific story of what there ultimately is, and how we fit into it.

Metaphysics has in the past basically always had to be built purely on arguments made with words—and indeed perhaps this is why it’s often been considered somewhat slippery and fragile. But now, with the kind of things we’ve discussed here, we’re beginning to have what we need to set up a solid, formal structure for metaphysics, in which we can progressively build a rich tower of definite conclusions.

Some of what there is to say relates to the ruliad, and is, in a sense, purely abstract and inevitable. But other parts relate to the “subjective” experience of observers—and, for us, basically human observers. So does metaphysics somehow need to involve itself with all the details of biology or, for that matter, psychology? The big surprise is that it doesn’t. Because the science says that knowing only very coarse things about observers (like that they are computationally bounded) already makes it possible to come to precise conclusions about certain features and laws they must perceive. There is in effect an emergent metaphysics.

The ruliad provides a form of answer to what there abstractly ultimately is. But to connect it to what for us there “really” is we need to know the essence of what we are like.

Investigating features of the ruliad is a lot about doing pure ruliology—and empirically studying what abstract simple programs do. Talking about observers is much more an exercise in metamodeling—and taking largely known models of the world, and trying to extract from them the abstract essence of what’s going on. To make a science of metaphysics somehow requires both of these.

But the exciting thing is that building on the computational paradigm and intuition from studying the computational universe we’re getting to the point where we can begin to give definite scientific answers to questions of metaphysics that for millennia have seemed like things about which one could just make arguments, but never come to conclusions. And like so many branches of philosophy before it, metaphysics now seems destined to make the transition from being a matter purely of philosophy to being one of science—finally giving us answers to the age old question of what there ultimately is.

Related Material

For other discussions of ideas explored here, see my recent Philosophical Writings »