The first workshop to define what is now the Santa Fe Institute took place on October 5–6, 1984. I was recently asked to give some reminiscences of the event, for a republication of a collection of papers derived from this and subsequent workshops.

It was a slightly dark room, decorated with Native American artifacts. Around it were tables arranged in a large rectangle, at which sat a couple dozen men (yes, all men), mostly in their sixties. The afternoon was wearing on, with many different people giving their various views about how to organize what amounted to a putative great new interdisciplinary university.

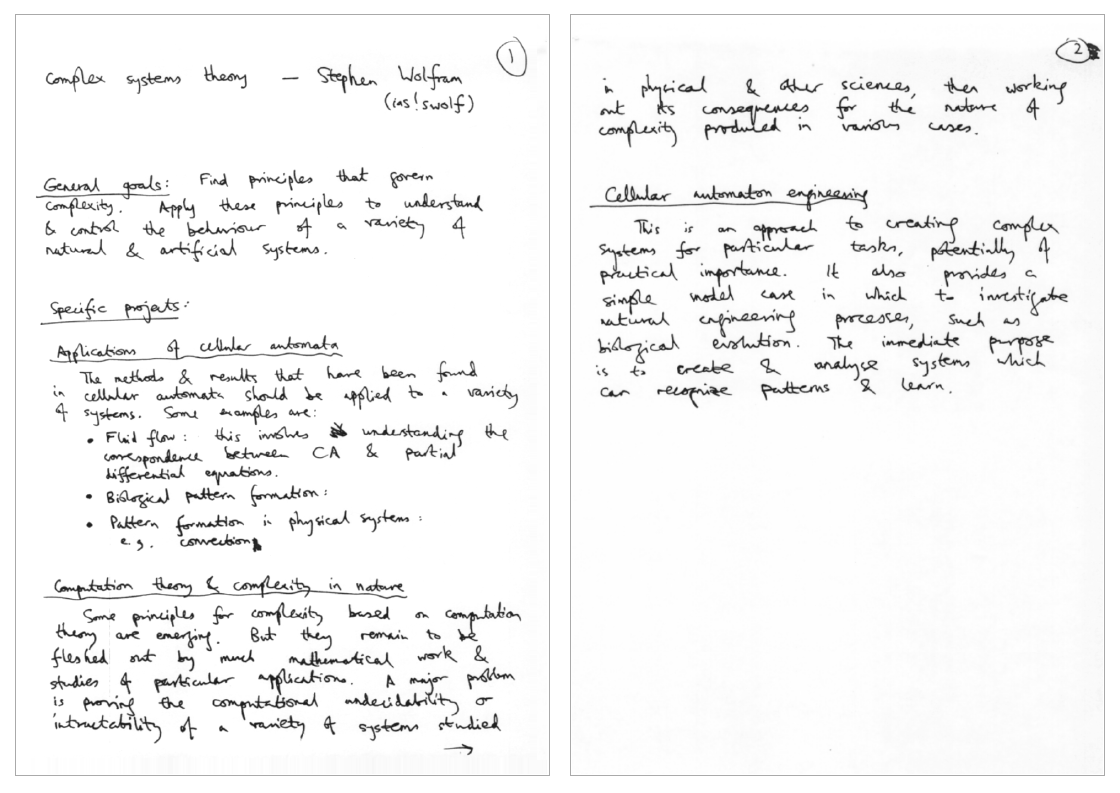

Here’s the original seating chart, together with a current view of the meeting room. (I’m only “Steve” to Americans currently over the age of 60…):

I think I was less patient in those days. But eventually I could stand it no longer. I don’t remember my exact words, but they boiled down to: “What are you going to do if you only raise a few million dollars, not two billion?” It was a strange moment. After all, I was by far the youngest person there—at 25 years old—and yet it seemed to have fallen to me to play the “let’s get real” role. (To be fair, I had founded my first tech company a couple of years earlier, and wasn’t a complete stranger to the world of grandiose “what-if” discussions, even if I was surprised, though more than a little charmed, to be seeing them in the sixty-something-year-old set.)

A fragment of my notes from the day record my feelings:

George Cowan (Manhattan Project alum, Los Alamos administrator, and founder of the Los Alamos Bank) was running the meeting, and I sensed a mixture of frustration and relief at my question. I don’t remember precisely what he said, but it boiled down to: “Well, what do you think we should do?” “Well”, I said, “I do have a suggestion”. I summarized it a bit, but then it was agreed that later that day I should give a more formal presentation. And that’s basically how I came to suggest that what would become the Santa Fe Institute should focus on what I called “Complex Systems Theory”.

Of course, there was a whole backstory to this. It basically began in 1972, when I was 12 years old, and saw the cover of a college physics textbook that purported to show an arrangement of simulated colliding molecules progressively becoming more random. I was fascinated by this phenomenon, and quite soon started trying to use a computer to understand it. I didn’t get too far with this. But it was the golden age of particle physics, and I was soon swept up in publishing papers about a variety of topics in particle physics and cosmology.

Still, in all sorts of different ways I kept on coming back to my interest in how randomness—or complexity—gets produced. In 1978 I went to Caltech as a graduate student, with Murray Gell-Mann (inventor of quarks, and the first chairman of the Santa Fe Institute) doing his part to recruit me by successfully tracking down a phone number for me in England. Then in 1979, as a way to help get physics done, I set about building my first large-scale computer language. In 1981, the first version was finished, I was installed as a faculty member at Caltech—and I decided it was time for me to try something more ambitious, and really see what I could figure out about my old interest in randomness and complexity.

By then I had picked away at many examples of complexity. In self-gravitating gases. In dendritic crystal growth. In road traffic flow. In neural networks. But the reductionist physicist in me wanted to drill down and find out what was underneath all these. And meanwhile the computer language designer in me thought, “Let’s just invent something and see what can be done with it”. Well, pretty soon I invented what I later found out were called cellular automata.

I didn’t expect that simple cellular automata would do anything particularly interesting. But I decided to try computer experiments on them anyway. And to my great surprise I discovered that—despite the simplicity of their construction—cellular automata can in fact produce behavior of great complexity. It’s a major shock to traditional scientific intuition—and, as I came to realize in later years, a clue to a whole new kind of science.

But for me the period from 1981 to 1984 was an exciting one, as I began to explore the computational universe of simple programs like cellular automata, and saw just how rich and unexpected it was. David Pines, as the editor of Reviews of Modern Physics, had done me the favor of publishing my first big paper on cellular automata (John Maddox, editor of Nature, had published a short summary a little earlier). Through the Center for Nonlinear Studies, I had started making visits to Los Alamos in 1981, and I initiated and co-organized the first-ever conference devoted to cellular automata, held at Los Alamos in 1983.

In 1983 I had left Caltech (primarily as a result of an unhappy interaction about intellectual property rights) and gone to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and begun to build a group there concerned with studying the basic science of complex systems. I wasn’t sure until quite a few years later just how general the phenomena I’d seen in cellular automata were. But I was pretty certain that there were at least many examples of complexity across all sorts of fields that they’d finally let one explain in a fundamental, theoretical way.

I’m not sure when I first heard about plans for what was then called the Rio Grande Institute. But I remember not being very hopeful about it; it seemed too correlated with the retirement plans of a group of older physicists. But meanwhile, people like Pete Carruthers (director of T Division at Los Alamos) were encouraging me to think about starting my own institute to pursue the kind of science I thought could be done.

I didn’t know quite what to make of the letter I received in July 1984 from Nick Metropolis (long-time Los Alamos scientist, and inventor of the Metropolis method). It described the nascent Rio Grande Institute as “a teaching and research institution responsive to the challenge of emerging new syntheses in science”. Murray Gell-Mann had told me that it would bring together physics and archaeology, linguistics and cosmology, and more. But at least in the circulated documents, the word “complexity” appeared quite often.

The invitation described the workshop as being “to examine a concept for a fresh approach to research and teaching in rapidly developing fields of scientific activity dealing with highly complex, interactive systems”. Murray Gell-Mann, who had become a sort of de facto intellectual leader of the effort, was given to quite flowery descriptions, and declared that the institute would be involved with “simplicity and complexity”.

When I arrived at the workshop it was clear that everyone wanted their favorite field to get a piece of the potential action. Should I even bring up my favorite emerging field? Or should I just make a few comments about computers and let the older guys do their thing?

As I listened to the talks and discussions, I kept wondering how what I was studying might relate to them. Quite often I really didn’t know. At the time I still believed, for example, that adaptive systems might have fundamentally different characteristics. But still, the term “complexity” kept on coming up. And if the Rio Grande Institute needed an area to concentrate on, it seemed that a general study of complexity would be the closest to being central to everything they were talking about.

I’m not sure quite what the people in the room made of my speech about “complex systems theory”. But I think I did succeed in making the point that there really could be a general “science of complexity”—and that things like cellular automata could show one how it might work. People had been talking about the complexity of this, or the complexity of that. But it seemed like I’d at least started the process of getting people to talk about complexity as an abstract thing one could expect to have general theories about.

After that first workshop, I had a few more interactions with what was to be the Santa Fe Institute. I still wasn’t sure what was going to happen with it—but the “science of complexity” idea did seem to be sticking. Meanwhile, however, I was forging ahead with my own plans to start a complex systems institute (I avoided the term “complexity theory” out of deference to the rather different field of computational complexity theory). I was talking to all sorts of universities, and in fact David Pines was encouraging me to consider the University of Illinois.

George Cowan asked me if I’d be interested in running the research program for the Santa Fe Institute, but by that point I was committed to starting my own operation, and it wasn’t long afterwards that I decided to do it at the University of Illinois. My Center for Complex Systems Research—and my journal Complex Systems—began operations in the summer of 1986.

I’m not sure how things would have been different if I’d ended up working with the Santa Fe Institute. But as it was, I rather quickly tired of the effort to raise money for complex systems research, and I was soon off creating what became Mathematica (and now the Wolfram Language), and starting my company Wolfram Research.

By the early 1990s, probably in no small part through the efforts of the Santa Fe Institute, “complexity” had actually become a popular buzzword, and, partly through a rather circuitous connection to climate science, funding had started pouring in. But having launched Mathematica and my company, I’d personally pretty much vanished from the scene, working quietly on using the tools I’d created to pursue my interests in basic science. I thought it would only take a couple of years, but in the end it took more than a decade.

I discovered a lot—and realized that, yes, the phenomena I’d first seen with cellular automata and talked about at the Santa Fe workshop were indeed a clue to a whole new kind of science, with all sorts of implications for long-standing problems and for the future. I packaged up what I’d figured out—and in 2002 published my magnum opus A New Kind of Science.

It was strange to reemerge after a decade and a half away. The Santa Fe Institute had continued to pursue the science of complexity. As something of a hermit in those years, I hadn’t interacted with it—but there was curiosity about what I was doing (highlighted, if nothing else, by a bizarre incident in 1998 involving “leaks” about my research). When my book came out in 2002 I was pleased that I thought I’d actually done what I talked about doing back at that Santa Fe workshop in 1984—as well as much more.

But by then almost nobody who’d been there in 1984 was still involved with the Santa Fe Institute, and instead there was a “new guard” (now, I believe, again departed), who, far from being pleased with my progress and success in broadening the field, actually responded with rather unseemly hostility.

It’s been an interesting journey from those days in October 1984. Today complex systems research is very definitely “a thing”, and there are hundreds of “complex systems” institutes around the world. (Though I still don’t think the basic science of complexity, as opposed to its applications, has received the attention it should.) But the Santa Fe Institute remains the prototypical example—and it’s not uncommon when I talk about complexity research for people to ask, “Is that like what the Santa Fe Institute does?”

“Well actually”, I sometimes say, “there’s a little footnote to history about that”. And off I go, talking about that Saturday afternoon back in October 1984—when I could be reached (as the notes I distributed said) through that newfangled thing called email at ias!swolf