It’s Just Adding One Word at a Time

That ChatGPT can automatically generate something that reads even superficially like human-written text is remarkable, and unexpected. But how does it do it? And why does it work? My purpose here is to give a rough outline of what’s going on inside ChatGPT—and then to explore why it is that it can do so well in producing what we might consider to be meaningful text. I should say at the outset that I’m going to focus on the big picture of what’s going on—and while I’ll mention some engineering details, I won’t get deeply into them. (And the essence of what I’ll say applies just as well to other current “large language models” [LLMs] as to ChatGPT.)

The first thing to explain is that what ChatGPT is always fundamentally trying to do is to produce a “reasonable continuation” of whatever text it’s got so far, where by “reasonable” we mean “what one might expect someone to write after seeing what people have written on billions of webpages, etc.”

So let’s say we’ve got the text “The best thing about AI is its ability to”. Imagine scanning billions of pages of human-written text (say on the web and in digitized books) and finding all instances of this text—then seeing what word comes next what fraction of the time. ChatGPT effectively does something like this, except that (as I’ll explain) it doesn’t look at literal text; it looks for things that in a certain sense “match in meaning”. But the end result is that it produces a ranked list of words that might follow, together with “probabilities”:

And the remarkable thing is that when ChatGPT does something like write an essay what it’s essentially doing is just asking over and over again “given the text so far, what should the next word be?”—and each time adding a word. (More precisely, as I’ll explain, it’s adding a “token”, which could be just a part of a word, which is why it can sometimes “make up new words”.)

But, OK, at each step it gets a list of words with probabilities. But which one should it actually pick to add to the essay (or whatever) that it’s writing? One might think it should be the “highest-ranked” word (i.e. the one to which the highest “probability” was assigned). But this is where a bit of voodoo begins to creep in. Because for some reason—that maybe one day we’ll have a scientific-style understanding of—if we always pick the highest-ranked word, we’ll typically get a very “flat” essay, that never seems to “show any creativity” (and even sometimes repeats word for word). But if sometimes (at random) we pick lower-ranked words, we get a “more interesting” essay.

The fact that there’s randomness here means that if we use the same prompt multiple times, we’re likely to get different essays each time. And, in keeping with the idea of voodoo, there’s a particular so-called “temperature” parameter that determines how often lower-ranked words will be used, and for essay generation, it turns out that a “temperature” of 0.8 seems best. (It’s worth emphasizing that there’s no “theory” being used here; it’s just a matter of what’s been found to work in practice. And for example the concept of “temperature” is there because exponential distributions familiar from statistical physics happen to be being used, but there’s no “physical” connection—at least so far as we know.)

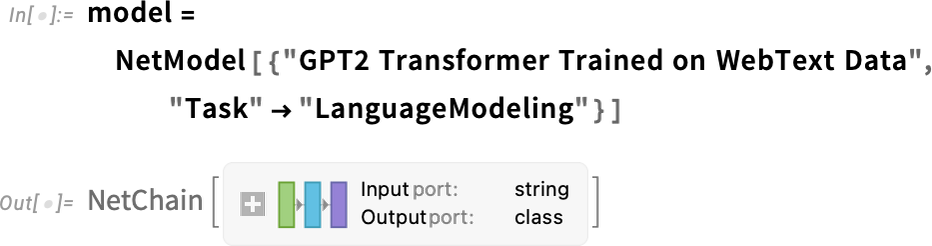

Before we go on I should explain that for purposes of exposition I’m mostly not going to use the full system that’s in ChatGPT; instead I’ll usually work with a simpler GPT-2 system, which has the nice feature that it’s small enough to be able to run on a standard desktop computer. And so for essentially everything I show I’ll be able to include explicit Wolfram Language code that you can immediately run on your computer. (Click any picture here to copy the code behind it.)

For example, here’s how to get the table of probabilities above. First, we have to retrieve the underlying “language model” neural net:

Later on, we’ll look inside this neural net, and talk about how it works. But for now we can just apply this “net model” as a black box to our text so far, and ask for the top 5 words by probability that the model says should follow:

This takes that result and makes it into an explicit formatted “dataset”:

Here’s what happens if one repeatedly “applies the model”—at each step adding the word that has the top probability (specified in this code as the “decision” from the model):

What happens if one goes on longer? In this (“zero temperature”) case what comes out soon gets rather confused and repetitive:

But what if instead of always picking the “top” word one sometimes randomly picks “non-top” words (with the “randomness” corresponding to “temperature” 0.8)? Again one can build up text:

And every time one does this, different random choices will be made, and the text will be different—as in these 5 examples:

It’s worth pointing out that even at the first step there are a lot of possible “next words” to choose from (at temperature 0.8), though their probabilities fall off quite quickly (and, yes, the straight line on this log-log plot corresponds to an n–1 “power-law” decay that’s very characteristic of the general statistics of language):

So what happens if one goes on longer? Here’s a random example. It’s better than the top-word (zero temperature) case, but still at best a bit weird:

This was done with the simplest GPT-2 model (from 2019). With the newer and bigger GPT-3 models the results are better. Here’s the top-word (zero temperature) text produced with the same “prompt”, but with the biggest GPT-3 model:

And here’s a random example at “temperature 0.8”:

Where Do the Probabilities Come From?

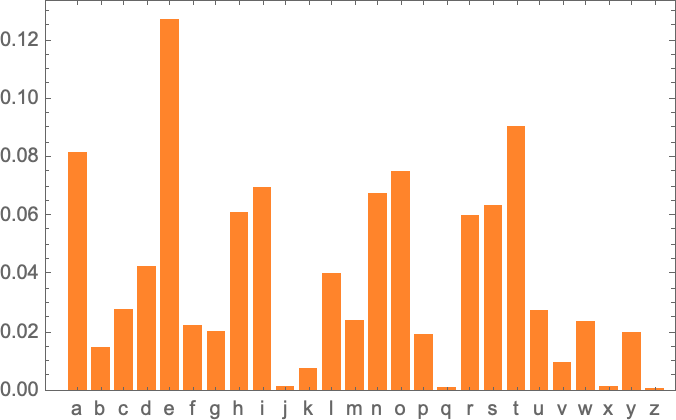

OK, so ChatGPT always picks its next word based on probabilities. But where do those probabilities come from? Let’s start with a simpler problem. Let’s consider generating English text one letter (rather than word) at a time. How can we work out what the probability for each letter should be?

A very minimal thing we could do is just take a sample of English text, and calculate how often different letters occur in it. So, for example, this counts letters in the Wikipedia article on “cats”:

And this does the same thing for “dogs”:

The results are similar, but not the same (“o” is no doubt more common in the “dogs” article because, after all, it occurs in the word “dog” itself). Still, if we take a large enough sample of English text we can expect to eventually get at least fairly consistent results:

Here’s a sample of what we get if we just generate a sequence of letters with these probabilities:

We can break this into “words” by adding in spaces as if they were letters with a certain probability:

We can do a slightly better job of making “words” by forcing the distribution of “word lengths” to agree with what it is in English:

We didn’t happen to get any “actual words” here, but the results are looking slightly better. To go further, though, we need to do more than just pick each letter separately at random. And, for example, we know that if we have a “q”, the next letter basically has to be “u”.

Here’s a plot of the probabilities for letters on their own:

And here’s a plot that shows the probabilities of pairs of letters (“2-grams”) in typical English text. The possible first letters are shown across the page, the second letters down the page:

And we see here, for example, that the “q” column is blank (zero probability) except on the “u” row. OK, so now instead of generating our “words” a single letter at a time, let’s generate them looking at two letters at a time, using these “2-gram” probabilities. Here’s a sample of the result—which happens to include a few “actual words”:

With sufficiently much English text we can get pretty good estimates not just for probabilities of single letters or pairs of letters (2-grams), but also for longer runs of letters. And if we generate “random words” with progressively longer n-gram probabilities, we see that they get progressively “more realistic”:

But let’s now assume—more or less as ChatGPT does—that we’re dealing with whole words, not letters. There are about 40,000 reasonably commonly used words in English. And by looking at a large corpus of English text (say a few million books, with altogether a few hundred billion words), we can get an estimate of how common each word is. And using this we can start generating “sentences”, in which each word is independently picked at random, with the same probability that it appears in the corpus. Here’s a sample of what we get:

Not surprisingly, this is nonsense. So how can we do better? Just like with letters, we can start taking into account not just probabilities for single words but probabilities for pairs or longer n-grams of words. Doing this for pairs, here are 5 examples of what we get, in all cases starting from the word “cat”:

It’s getting slightly more “sensible looking”. And we might imagine that if we were able to use sufficiently long n-grams we’d basically “get a ChatGPT”—in the sense that we’d get something that would generate essay-length sequences of words with the “correct overall essay probabilities”. But here’s the problem: there just isn’t even close to enough English text that’s ever been written to be able to deduce those probabilities.

In a crawl of the web there might be a few hundred billion words; in books that have been digitized there might be another hundred billion words. But with 40,000 common words, even the number of possible 2-grams is already 1.6 billion—and the number of possible 3-grams is 60 trillion. So there’s no way we can estimate the probabilities even for all of these from text that’s out there. And by the time we get to “essay fragments” of 20 words, the number of possibilities is larger than the number of particles in the universe, so in a sense they could never all be written down.

So what can we do? The big idea is to make a model that lets us estimate the probabilities with which sequences should occur—even though we’ve never explicitly seen those sequences in the corpus of text we’ve looked at. And at the core of ChatGPT is precisely a so-called “large language model” (LLM) that’s been built to do a good job of estimating those probabilities.

What Is a Model?

Say you want to know (as Galileo did back in the late 1500s) how long it’s going to take a cannon ball dropped from each floor of the Tower of Pisa to hit the ground. Well, you could just measure it in each case and make a table of the results. Or you could do what is the essence of theoretical science: make a model that gives some kind of procedure for computing the answer rather than just measuring and remembering each case.

Let’s imagine we have (somewhat idealized) data for how long the cannon ball takes to fall from various floors:

How do we figure out how long it’s going to take to fall from a floor we don’t explicitly have data about? In this particular case, we can use known laws of physics to work it out. But say all we’ve got is the data, and we don’t know what underlying laws govern it. Then we might make a mathematical guess, like that perhaps we should use a straight line as a model:

We could pick different straight lines. But this is the one that’s on average closest to the data we’re given. And from this straight line we can estimate the time to fall for any floor.

How did we know to try using a straight line here? At some level we didn’t. It’s just something that’s mathematically simple, and we’re used to the fact that lots of data we measure turns out to be well fit by mathematically simple things. We could try something mathematically more complicated—say a + b x + c x2—and then in this case we do better:

Things can go quite wrong, though. Like here’s the best we can do with a + b/x + c sin(x):

It is worth understanding that there’s never a “model-less model”. Any model you use has some particular underlying structure—then a certain set of “knobs you can turn” (i.e. parameters you can set) to fit your data. And in the case of ChatGPT, lots of such “knobs” are used—actually, 175 billion of them.

But the remarkable thing is that the underlying structure of ChatGPT—with “just” that many parameters—is sufficient to make a model that computes next-word probabilities “well enough” to give us reasonable essay-length pieces of text.

Models for Human-Like Tasks

The example we gave above involves making a model for numerical data that essentially comes from simple physics—where we’ve known for several centuries that “simple mathematics applies”. But for ChatGPT we have to make a model of human-language text of the kind produced by a human brain. And for something like that we don’t (at least yet) have anything like “simple mathematics”. So what might a model of it be like?

Before we talk about language, let’s talk about another human-like task: recognizing images. And as a simple example of this, let’s consider images of digits (and, yes, this is a classic machine learning example):

One thing we could do is get a bunch of sample images for each digit:

Then to find out if an image we’re given as input corresponds to a particular digit we could just do an explicit pixel-by-pixel comparison with the samples we have. But as humans we certainly seem to do something better—because we can still recognize digits, even when they’re for example handwritten, and have all sorts of modifications and distortions:

When we made a model for our numerical data above, we were able to take a numerical value x that we were given, and just compute a + b x for particular a and b. So if we treat the gray-level value of each pixel here as some variable xi is there some function of all those variables that—when evaluated—tells us what digit the image is of? It turns out that it’s possible to construct such a function. Not surprisingly, it’s not particularly simple, though. And a typical example might involve perhaps half a million mathematical operations.

But the end result is that if we feed the collection of pixel values for an image into this function, out will come the number specifying which digit we have an image of. Later, we’ll talk about how such a function can be constructed, and the idea of neural nets. But for now let’s treat the function as black box, where we feed in images of, say, handwritten digits (as arrays of pixel values) and we get out the numbers these correspond to:

But what’s really going on here? Let’s say we progressively blur a digit. For a little while our function still “recognizes” it, here as a “2”. But soon it “loses it”, and starts giving the “wrong” result:

But why do we say it’s the “wrong” result? In this case, we know we got all the images by blurring a “2”. But if our goal is to produce a model of what humans can do in recognizing images, the real question to ask is what a human would have done if presented with one of those blurred images, without knowing where it came from.

And we have a “good model” if the results we get from our function typically agree with what a human would say. And the nontrivial scientific fact is that for an image-recognition task like this we now basically know how to construct functions that do this.

Can we “mathematically prove” that they work? Well, no. Because to do that we’d have to have a mathematical theory of what we humans are doing. Take the “2” image and change a few pixels. We might imagine that with only a few pixels “out of place” we should still consider the image a “2”. But how far should that go? It’s a question of human visual perception. And, yes, the answer would no doubt be different for bees or octopuses—and potentially utterly different for putative aliens.

Neural Nets

OK, so how do our typical models for tasks like image recognition actually work? The most popular—and successful—current approach uses neural nets. Invented—in a form remarkably close to their use today—in the 1940s, neural nets can be thought of as simple idealizations of how brains seem to work.

In human brains there are about 100 billion neurons (nerve cells), each capable of producing an electrical pulse up to perhaps a thousand times a second. The neurons are connected in a complicated net, with each neuron having tree-like branches allowing it to pass electrical signals to perhaps thousands of other neurons. And in a rough approximation, whether any given neuron produces an electrical pulse at a given moment depends on what pulses it’s received from other neurons—with different connections contributing with different “weights”.

When we “see an image” what’s happening is that when photons of light from the image fall on (“photoreceptor”) cells at the back of our eyes they produce electrical signals in nerve cells. These nerve cells are connected to other nerve cells, and eventually the signals go through a whole sequence of layers of neurons. And it’s in this process that we “recognize” the image, eventually “forming the thought” that we’re “seeing a 2” (and maybe in the end doing something like saying the word “two” out loud).

The “black-box” function from the previous section is a “mathematicized” version of such a neural net. It happens to have 11 layers (though only 4 “core layers”):

There’s nothing particularly “theoretically derived” about this neural net; it’s just something that—back in 1998—was constructed as a piece of engineering, and found to work. (Of course, that’s not much different from how we might describe our brains as having been produced through the process of biological evolution.)

OK, but how does a neural net like this “recognize things”? The key is the notion of attractors. Imagine we’ve got handwritten images of 1’s and 2’s:

We somehow want all the 1’s to “be attracted to one place”, and all the 2’s to “be attracted to another place”. Or, put a different way, if an image is somehow “closer to being a 1” than to being a 2, we want it to end up in the “1 place” and vice versa.

As a straightforward analogy, let’s say we have certain positions in the plane, indicated by dots (in a real-life setting they might be positions of coffee shops). Then we might imagine that starting from any point on the plane we’d always want to end up at the closest dot (i.e. we’d always go to the closest coffee shop). We can represent this by dividing the plane into regions (“attractor basins”) separated by idealized “watersheds”:

We can think of this as implementing a kind of “recognition task” in which we’re not doing something like identifying what digit a given image “looks most like”—but rather we’re just, quite directly, seeing what dot a given point is closest to. (The “Voronoi diagram” setup we’re showing here separates points in 2D Euclidean space; the digit recognition task can be thought of as doing something very similar—but in a 784-dimensional space formed from the gray levels of all the pixels in each image.)

So how do we make a neural net “do a recognition task”? Let’s consider this very simple case:

Our goal is to take an “input” corresponding to a position {x,y}—and then to “recognize” it as whichever of the three points it’s closest to. Or, in other words, we want the neural net to compute a function of {x,y} like:

So how do we do this with a neural net? Ultimately a neural net is a connected collection of idealized “neurons”—usually arranged in layers—with a simple example being:

Each “neuron” is effectively set up to evaluate a simple numerical function. And to “use” the network, we simply feed numbers (like our coordinates x and y) in at the top, then have neurons on each layer “evaluate their functions” and feed the results forward through the network—eventually producing the final result at the bottom:

In the traditional (biologically inspired) setup each neuron effectively has a certain set of “incoming connections” from the neurons on the previous layer, with each connection being assigned a certain “weight” (which can be a positive or negative number). The value of a given neuron is determined by multiplying the values of “previous neurons” by their corresponding weights, then adding these up and adding a constant—and finally applying a “thresholding” (or “activation”) function. In mathematical terms, if a neuron has inputs

Computing w . x + b is just a matter of matrix multiplication and addition. The “activation function” f introduces nonlinearity (and ultimately is what leads to nontrivial behavior). Various activation functions commonly get used; here we’ll just use Ramp (or ReLU):

For each task we want the neural net to perform (or, equivalently, for each overall function we want it to evaluate) we’ll have different choices of weights. (And—as we’ll discuss later—these weights are normally determined by “training” the neural net using machine learning from examples of the outputs we want.)

Ultimately, every neural net just corresponds to some overall mathematical function—though it may be messy to write out. For the example above, it would be:

The neural net of ChatGPT also just corresponds to a mathematical function like this—but effectively with billions of terms.

But let’s go back to individual neurons. Here are some examples of the functions a neuron with two inputs (representing coordinates x and y) can compute with various choices of weights and constants (and Ramp as activation function):

But what about the larger network from above? Well, here’s what it computes:

It’s not quite “right”, but it’s close to the “nearest point” function we showed above.

Let’s see what happens with some other neural nets. In each case, as we’ll explain later, we’re using machine learning to find the best choice of weights. Then we’re showing here what the neural net with those weights computes:

Bigger networks generally do better at approximating the function we’re aiming for. And in the “middle of each attractor basin” we typically get exactly the answer we want. But at the boundaries—where the neural net “has a hard time making up its mind”—things can be messier.

With this simple mathematical-style “recognition task” it’s clear what the “right answer” is. But in the problem of recognizing handwritten digits, it’s not so clear. What if someone wrote a “2” so badly it looked like a “7”, etc.? Still, we can ask how a neural net distinguishes digits—and this gives an indication:

Can we say “mathematically” how the network makes its distinctions? Not really. It’s just “doing what the neural net does”. But it turns out that that normally seems to agree fairly well with the distinctions we humans make.

Let’s take a more elaborate example. Let’s say we have images of cats and dogs. And we have a neural net that’s been trained to distinguish them. Here’s what it might do on some examples:

Now it’s even less clear what the “right answer” is. What about a dog dressed in a cat suit? Etc. Whatever input it’s given the neural net will generate an answer, and in a way reasonably consistent with how humans might. As I’ve said above, that’s not a fact we can “derive from first principles”. It’s just something that’s empirically been found to be true, at least in certain domains. But it’s a key reason why neural nets are useful: that they somehow capture a “human-like” way of doing things.

Show yourself a picture of a cat, and ask “Why is that a cat?”. Maybe you’d start saying “Well, I see its pointy ears, etc.” But it’s not very easy to explain how you recognized the image as a cat. It’s just that somehow your brain figured that out. But for a brain there’s no way (at least yet) to “go inside” and see how it figured it out. What about for an (artificial) neural net? Well, it’s straightforward to see what each “neuron” does when you show a picture of a cat. But even to get a basic visualization is usually very difficult.

In the final net that we used for the “nearest point” problem above there are 17 neurons. In the net for recognizing handwritten digits there are 2190. And in the net we’re using to recognize cats and dogs there are 60,650. Normally it would be pretty difficult to visualize what amounts to 60,650-dimensional space. But because this is a network set up to deal with images, many of its layers of neurons are organized into arrays, like the arrays of pixels it’s looking at.

And if we take a typical cat image

then we can represent the states of neurons at the first layer by a collection of derived images—many of which we can readily interpret as being things like “the cat without its background”, or “the outline of the cat”:

By the 10th layer it’s harder to interpret what’s going on:

But in general we might say that the neural net is “picking out certain features” (maybe pointy ears are among them), and using these to determine what the image is of. But are those features ones for which we have names—like “pointy ears”? Mostly not.

Are our brains using similar features? Mostly we don’t know. But it’s notable that the first few layers of a neural net like the one we’re showing here seem to pick out aspects of images (like edges of objects) that seem to be similar to ones we know are picked out by the first level of visual processing in brains.

But let’s say we want a “theory of cat recognition” in neural nets. We can say: “Look, this particular net does it”—and immediately that gives us some sense of “how hard a problem” it is (and, for example, how many neurons or layers might be needed). But at least as of now we don’t have a way to “give a narrative description” of what the network is doing. And maybe that’s because it truly is computationally irreducible, and there’s no general way to find what it does except by explicitly tracing each step. Or maybe it’s just that we haven’t “figured out the science”, and identified the “natural laws” that allow us to summarize what’s going on.

We’ll encounter the same kinds of issues when we talk about generating language with ChatGPT. And again it’s not clear whether there are ways to “summarize what it’s doing”. But the richness and detail of language (and our experience with it) may allow us to get further than with images.

Machine Learning, and the Training of Neural Nets

We’ve been talking so far about neural nets that “already know” how to do particular tasks. But what makes neural nets so useful (presumably also in brains) is that not only can they in principle do all sorts of tasks, but they can be incrementally “trained from examples” to do those tasks.

When we make a neural net to distinguish cats from dogs we don’t effectively have to write a program that (say) explicitly finds whiskers; instead we just show lots of examples of what’s a cat and what’s a dog, and then have the network “machine learn” from these how to distinguish them.

And the point is that the trained network “generalizes” from the particular examples it’s shown. Just as we’ve seen above, it isn’t simply that the network recognizes the particular pixel pattern of an example cat image it was shown; rather it’s that the neural net somehow manages to distinguish images on the basis of what we consider to be some kind of “general catness”.

So how does neural net training actually work? Essentially what we’re always trying to do is to find weights that make the neural net successfully reproduce the examples we’ve given. And then we’re relying on the neural net to “interpolate” (or “generalize”) “between” these examples in a “reasonable” way.

Let’s look at a problem even simpler than the nearest-point one above. Let’s just try to get a neural net to learn the function:

For this task, we’ll need a network that has just one input and one output, like:

But what weights, etc. should we be using? With every possible set of weights the neural net will compute some function. And, for example, here’s what it does with a few randomly chosen sets of weights:

And, yes, we can plainly see that in none of these cases does it get even close to reproducing the function we want. So how do we find weights that will reproduce the function?

The basic idea is to supply lots of “input → output” examples to “learn from”—and then to try to find weights that will reproduce these examples. Here’s the result of doing that with progressively more examples:

At each stage in this “training” the weights in the network are progressively adjusted—and we see that eventually we get a network that successfully reproduces the function we want. So how do we adjust the weights? The basic idea is at each stage to see “how far away we are” from getting the function we want—and then to update the weights in such a way as to get closer.

To find out “how far away we are” we compute what’s usually called a “loss function” (or sometimes “cost function”). Here we’re using a simple (L2) loss function that’s just the sum of the squares of the differences between the values we get, and the true values. And what we see is that as our training process progresses, the loss function progressively decreases (following a certain “learning curve” that’s different for different tasks)—until we reach a point where the network (at least to a good approximation) successfully reproduces the function we want:

Alright, so the last essential piece to explain is how the weights are adjusted to reduce the loss function. As we’ve said, the loss function gives us a “distance” between the values we’ve got, and the true values. But the “values we’ve got” are determined at each stage by the current version of neural net—and by the weights in it. But now imagine that the weights are variables—say wi. We want to find out how to adjust the values of these variables to minimize the loss that depends on them.

For example, imagine (in an incredible simplification of typical neural nets used in practice) that we have just two weights w1 and w2. Then we might have a loss that as a function of w1 and w2 looks like this:

Numerical analysis provides a variety of techniques for finding the minimum in cases like this. But a typical approach is just to progressively follow the path of steepest descent from whatever previous w1, w2 we had:

Like water flowing down a mountain, all that’s guaranteed is that this procedure will end up at some local minimum of the surface (“a mountain lake”); it might well not reach the ultimate global minimum.

It’s not obvious that it would be feasible to find the path of the steepest descent on the “weight landscape”. But calculus comes to the rescue. As we mentioned above, one can always think of a neural net as computing a mathematical function—that depends on its inputs, and its weights. But now consider differentiating with respect to these weights. It turns out that the chain rule of calculus in effect lets us “unravel” the operations done by successive layers in the neural net. And the result is that we can—at least in some local approximation—“invert” the operation of the neural net, and progressively find weights that minimize the loss associated with the output.

The picture above shows the kind of minimization we might need to do in the unrealistically simple case of just 2 weights. But it turns out that even with many more weights (ChatGPT uses 175 billion) it’s still possible to do the minimization, at least to some level of approximation. And in fact the big breakthrough in “deep learning” that occurred around 2011 was associated with the discovery that in some sense it can be easier to do (at least approximate) minimization when there are lots of weights involved than when there are fairly few.

In other words—somewhat counterintuitively—it can be easier to solve more complicated problems with neural nets than simpler ones. And the rough reason for this seems to be that when one has a lot of “weight variables” one has a high-dimensional space with “lots of different directions” that can lead one to the minimum—whereas with fewer variables it’s easier to end up getting stuck in a local minimum (“mountain lake”) from which there’s no “direction to get out”.

It’s worth pointing out that in typical cases there are many different collections of weights that will all give neural nets that have pretty much the same performance. And usually in practical neural net training there are lots of random choices made—that lead to “different-but-equivalent solutions”, like these:

But each such “different solution” will have at least slightly different behavior. And if we ask, say, for an “extrapolation” outside the region where we gave training examples, we can get dramatically different results:

But which of these is “right”? There’s really no way to say. They’re all “consistent with the observed data”. But they all correspond to different “innate” ways to “think about” what to do “outside the box”. And some may seem “more reasonable” to us humans than others.

The Practice and Lore of Neural Net Training

Particularly over the past decade, there’ve been many advances in the art of training neural nets. And, yes, it is basically an art. Sometimes—especially in retrospect—one can see at least a glimmer of a “scientific explanation” for something that’s being done. But mostly things have been discovered by trial and error, adding ideas and tricks that have progressively built a significant lore about how to work with neural nets.

There are several key parts. First, there’s the matter of what architecture of neural net one should use for a particular task. Then there’s the critical issue of how one’s going to get the data on which to train the neural net. And increasingly one isn’t dealing with training a net from scratch: instead a new net can either directly incorporate another already-trained net, or at least can use that net to generate more training examples for itself.

One might have thought that for every particular kind of task one would need a different architecture of neural net. But what’s been found is that the same architecture often seems to work even for apparently quite different tasks. At some level this reminds one of the idea of universal computation (and my Principle of Computational Equivalence), but, as I’ll discuss later, I think it’s more a reflection of the fact that the tasks we’re typically trying to get neural nets to do are “human-like” ones—and neural nets can capture quite general “human-like processes”.

In earlier days of neural nets, there tended to be the idea that one should “make the neural net do as little as possible”. For example, in converting speech to text it was thought that one should first analyze the audio of the speech, break it into phonemes, etc. But what was found is that—at least for “human-like tasks”—it’s usually better just to try to train the neural net on the “end-to-end problem”, letting it “discover” the necessary intermediate features, encodings, etc. for itself.

There was also the idea that one should introduce complicated individual components into the neural net, to let it in effect “explicitly implement particular algorithmic ideas”. But once again, this has mostly turned out not to be worthwhile; instead, it’s better just to deal with very simple components and let them “organize themselves” (albeit usually in ways we can’t understand) to achieve (presumably) the equivalent of those algorithmic ideas.

That’s not to say that there are no “structuring ideas” that are relevant for neural nets. Thus, for example, having 2D arrays of neurons with local connections seems at least very useful in the early stages of processing images. And having patterns of connectivity that concentrate on “looking back in sequences” seems useful—as we’ll see later—in dealing with things like human language, for example in ChatGPT.

But an important feature of neural nets is that—like computers in general—they’re ultimately just dealing with data. And current neural nets—with current approaches to neural net training—specifically deal with arrays of numbers. But in the course of processing, those arrays can be completely rearranged and reshaped. And as an example, the network we used for identifying digits above starts with a 2D “image-like” array, quickly “thickening” to many channels, but then “concentrating down” into a 1D array that will ultimately contain elements representing the different possible output digits:

But, OK, how can one tell how big a neural net one will need for a particular task? It’s something of an art. At some level the key thing is to know “how hard the task is”. But for human-like tasks that’s typically very hard to estimate. Yes, there may be a systematic way to do the task very “mechanically” by computer. But it’s hard to know if there are what one might think of as tricks or shortcuts that allow one to do the task at least at a “human-like level” vastly more easily. It might take enumerating a giant game tree to “mechanically” play a certain game; but there might be a much easier (“heuristic”) way to achieve “human-level play”.

When one’s dealing with tiny neural nets and simple tasks one can sometimes explicitly see that one “can’t get there from here”. For example, here’s the best one seems to be able to do on the task from the previous section with a few small neural nets:

And what we see is that if the net is too small, it just can’t reproduce the function we want. But above some size, it has no problem—at least if one trains it for long enough, with enough examples. And, by the way, these pictures illustrate a piece of neural net lore: that one can often get away with a smaller network if there’s a “squeeze” in the middle that forces everything to go through a smaller intermediate number of neurons. (It’s also worth mentioning that “no-intermediate-layer”—or so-called “perceptron”—networks can only learn essentially linear functions—but as soon as there’s even one intermediate layer it’s always in principle possible to approximate any function arbitrarily well, at least if one has enough neurons, though to make it feasibly trainable one typically has some kind of regularization or normalization.)

OK, so let’s say one’s settled on a certain neural net architecture. Now there’s the issue of getting data to train the network with. And many of the practical challenges around neural nets—and machine learning in general—center on acquiring or preparing the necessary training data. In many cases (“supervised learning”) one wants to get explicit examples of inputs and the outputs one is expecting from them. Thus, for example, one might want images tagged by what’s in them, or some other attribute. And maybe one will have to explicitly go through—usually with great effort—and do the tagging. But very often it turns out to be possible to piggyback on something that’s already been done, or use it as some kind of proxy. And so, for example, one might use alt tags that have been provided for images on the web. Or, in a different domain, one might use closed captions that have been created for videos. Or—for language translation training—one might use parallel versions of webpages or other documents that exist in different languages.

How much data do you need to show a neural net to train it for a particular task? Again, it’s hard to estimate from first principles. Certainly the requirements can be dramatically reduced by using “transfer learning” to “transfer in” things like lists of important features that have already been learned in another network. But generally neural nets need to “see a lot of examples” to train well. And at least for some tasks it’s an important piece of neural net lore that the examples can be incredibly repetitive. And indeed it’s a standard strategy to just show a neural net all the examples one has, over and over again. In each of these “training rounds” (or “epochs”) the neural net will be in at least a slightly different state, and somehow “reminding it” of a particular example is useful in getting it to “remember that example”. (And, yes, perhaps this is analogous to the usefulness of repetition in human memorization.)

But often just repeating the same example over and over again isn’t enough. It’s also necessary to show the neural net variations of the example. And it’s a feature of neural net lore that those “data augmentation” variations don’t have to be sophisticated to be useful. Just slightly modifying images with basic image processing can make them essentially “as good as new” for neural net training. And, similarly, when one’s run out of actual video, etc. for training self-driving cars, one can go on and just get data from running simulations in a model videogame-like environment without all the detail of actual real-world scenes.

How about something like ChatGPT? Well, it has the nice feature that it can do “unsupervised learning”, making it much easier to get it examples to train from. Recall that the basic task for ChatGPT is to figure out how to continue a piece of text that it’s been given. So to get it “training examples” all one has to do is get a piece of text, and mask out the end of it, and then use this as the “input to train from”—with the “output” being the complete, unmasked piece of text. We’ll discuss this more later, but the main point is that—unlike, say, for learning what’s in images—there’s no “explicit tagging” needed; ChatGPT can in effect just learn directly from whatever examples of text it’s given.

OK, so what about the actual learning process in a neural net? In the end it’s all about determining what weights will best capture the training examples that have been given. And there are all sorts of detailed choices and “hyperparameter settings” (so called because the weights can be thought of as “parameters”) that can be used to tweak how this is done. There are different choices of loss function (sum of squares, sum of absolute values, etc.). There are different ways to do loss minimization (how far in weight space to move at each step, etc.). And then there are questions like how big a “batch” of examples to show to get each successive estimate of the loss one’s trying to minimize. And, yes, one can apply machine learning (as we do, for example, in Wolfram Language) to automate machine learning—and to automatically set things like hyperparameters.

But in the end the whole process of training can be characterized by seeing how the loss progressively decreases (as in this Wolfram Language progress monitor for a small training):

And what one typically sees is that the loss decreases for a while, but eventually flattens out at some constant value. If that value is sufficiently small, then the training can be considered successful; otherwise it’s probably a sign one should try changing the network architecture.

Can one tell how long it should take for the “learning curve” to flatten out? Like for so many other things, there seem to be approximate power-law scaling relationships that depend on the size of neural net and amount of data one’s using. But the general conclusion is that training a neural net is hard—and takes a lot of computational effort. And as a practical matter, the vast majority of that effort is spent doing operations on arrays of numbers, which is what GPUs are good at—which is why neural net training is typically limited by the availability of GPUs.

In the future, will there be fundamentally better ways to train neural nets—or generally do what neural nets do? Almost certainly, I think. The fundamental idea of neural nets is to create a flexible “computing fabric” out of a large number of simple (essentially identical) components—and to have this “fabric” be one that can be incrementally modified to learn from examples. In current neural nets, one’s essentially using the ideas of calculus—applied to real numbers—to do that incremental modification. But it’s increasingly clear that having high-precision numbers doesn’t matter; 8 bits or less might be enough even with current methods.

With computational systems like cellular automata that basically operate in parallel on many individual bits it’s never been clear how to do this kind of incremental modification, but there’s no reason to think it isn’t possible. And in fact, much like with the “deep-learning breakthrough of 2012” it may be that such incremental modification will effectively be easier in more complicated cases than in simple ones.

Neural nets—perhaps a bit like brains—are set up to have an essentially fixed network of neurons, with what’s modified being the strength (“weight”) of connections between them. (Perhaps in at least young brains significant numbers of wholly new connections can also grow.) But while this might be a convenient setup for biology, it’s not at all clear that it’s even close to the best way to achieve the functionality we need. And something that involves the equivalent of progressive network rewriting (perhaps reminiscent of our Physics Project) might well ultimately be better.

But even within the framework of existing neural nets there’s currently a crucial limitation: neural net training as it’s now done is fundamentally sequential, with the effects of each batch of examples being propagated back to update the weights. And indeed with current computer hardware—even taking into account GPUs—most of a neural net is “idle” most of the time during training, with just one part at a time being updated. And in a sense this is because our current computers tend to have memory that is separate from their CPUs (or GPUs). But in brains it’s presumably different—with every “memory element” (i.e. neuron) also being a potentially active computational element. And if we could set up our future computer hardware this way it might become possible to do training much more efficiently.

“Surely a Network That’s Big Enough Can Do Anything!”

The capabilities of something like ChatGPT seem so impressive that one might imagine that if one could just “keep going” and train larger and larger neural networks, then they’d eventually be able to “do everything”. And if one’s concerned with things that are readily accessible to immediate human thinking, it’s quite possible that this is the case. But the lesson of the past several hundred years of science is that there are things that can be figured out by formal processes, but aren’t readily accessible to immediate human thinking.

Nontrivial mathematics is one big example. But the general case is really computation. And ultimately the issue is the phenomenon of computational irreducibility. There are some computations which one might think would take many steps to do, but which can in fact be “reduced” to something quite immediate. But the discovery of computational irreducibility implies that this doesn’t always work. And instead there are processes—probably like the one below—where to work out what happens inevitably requires essentially tracing each computational step:

The kinds of things that we normally do with our brains are presumably specifically chosen to avoid computational irreducibility. It takes special effort to do math in one’s brain. And it’s in practice largely impossible to “think through” the steps in the operation of any nontrivial program just in one’s brain.

But of course for that we have computers. And with computers we can readily do long, computationally irreducible things. And the key point is that there’s in general no shortcut for these.

Yes, we could memorize lots of specific examples of what happens in some particular computational system. And maybe we could even see some (“computationally reducible”) patterns that would allow us to do a little generalization. But the point is that computational irreducibility means that we can never guarantee that the unexpected won’t happen—and it’s only by explicitly doing the computation that you can tell what actually happens in any particular case.

And in the end there’s just a fundamental tension between learnability and computational irreducibility. Learning involves in effect compressing data by leveraging regularities. But computational irreducibility implies that ultimately there’s a limit to what regularities there may be.

As a practical matter, one can imagine building little computational devices—like cellular automata or Turing machines—into trainable systems like neural nets. And indeed such devices can serve as good “tools” for the neural net—like Wolfram|Alpha can be a good tool for ChatGPT. But computational irreducibility implies that one can’t expect to “get inside” those devices and have them learn.

Or put another way, there’s an ultimate tradeoff between capability and trainability: the more you want a system to make “true use” of its computational capabilities, the more it’s going to show computational irreducibility, and the less it’s going to be trainable. And the more it’s fundamentally trainable, the less it’s going to be able to do sophisticated computation.

(For ChatGPT as it currently is, the situation is actually much more extreme, because the neural net used to generate each token of output is a pure “feed-forward” network, without loops, and therefore has no ability to do any kind of computation with nontrivial “control flow”.)

Of course, one might wonder whether it’s actually important to be able to do irreducible computations. And indeed for much of human history it wasn’t particularly important. But our modern technological world has been built on engineering that makes use of at least mathematical computations—and increasingly also more general computations. And if we look at the natural world, it’s full of irreducible computation—that we’re slowly understanding how to emulate and use for our technological purposes.

Yes, a neural net can certainly notice the kinds of regularities in the natural world that we might also readily notice with “unaided human thinking”. But if we want to work out things that are in the purview of mathematical or computational science the neural net isn’t going to be able to do it—unless it effectively “uses as a tool” an “ordinary” computational system.

But there’s something potentially confusing about all of this. In the past there were plenty of tasks—including writing essays—that we’ve assumed were somehow “fundamentally too hard” for computers. And now that we see them done by the likes of ChatGPT we tend to suddenly think that computers must have become vastly more powerful—in particular surpassing things they were already basically able to do (like progressively computing the behavior of computational systems like cellular automata).

But this isn’t the right conclusion to draw. Computationally irreducible processes are still computationally irreducible, and are still fundamentally hard for computers—even if computers can readily compute their individual steps. And instead what we should conclude is that tasks—like writing essays—that we humans could do, but we didn’t think computers could do, are actually in some sense computationally easier than we thought.

In other words, the reason a neural net can be successful in writing an essay is because writing an essay turns out to be a “computationally shallower” problem than we thought. And in a sense this takes us closer to “having a theory” of how we humans manage to do things like writing essays, or in general deal with language.

If you had a big enough neural net then, yes, you might be able to do whatever humans can readily do. But you wouldn’t capture what the natural world in general can do—or that the tools that we’ve fashioned from the natural world can do. And it’s the use of those tools—both practical and conceptual—that have allowed us in recent centuries to transcend the boundaries of what’s accessible to “pure unaided human thought”, and capture for human purposes more of what’s out there in the physical and computational universe.

The Concept of Embeddings

Neural nets—at least as they’re currently set up—are fundamentally based on numbers. So if we’re going to to use them to work on something like text we’ll need a way to represent our text with numbers. And certainly we could start (essentially as ChatGPT does) by just assigning a number to every word in the dictionary. But there’s an important idea—that’s for example central to ChatGPT—that goes beyond that. And it’s the idea of “embeddings”. One can think of an embedding as a way to try to represent the “essence” of something by an array of numbers—with the property that “nearby things” are represented by nearby numbers.

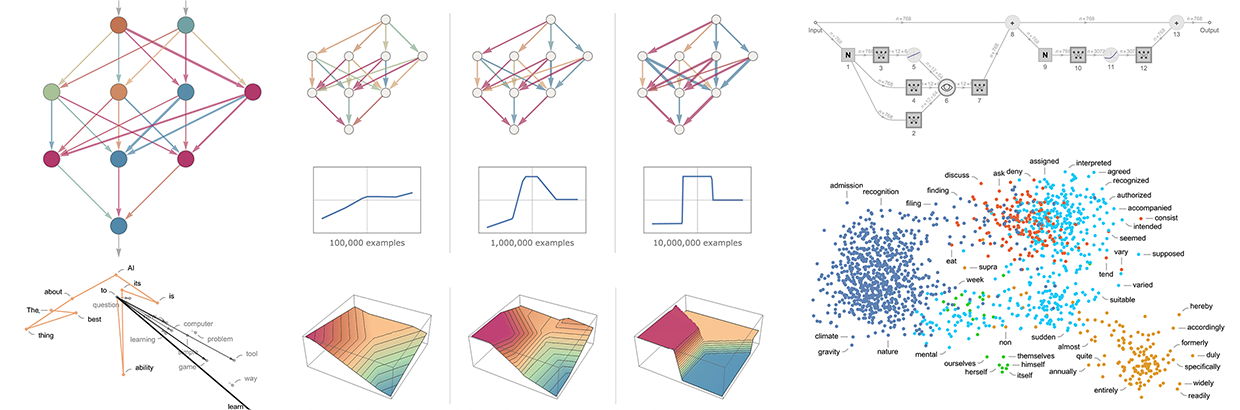

And so, for example, we can think of a word embedding as trying to lay out words in a kind of “meaning space” in which words that are somehow “nearby in meaning” appear nearby in the embedding. The actual embeddings that are used—say in ChatGPT—tend to involve large lists of numbers. But if we project down to 2D, we can show examples of how words are laid out by the embedding:

And, yes, what we see does remarkably well in capturing typical everyday impressions. But how can we construct such an embedding? Roughly the idea is to look at large amounts of text (here 5 billion words from the web) and then see “how similar” the “environments” are in which different words appear. So, for example, “alligator” and “crocodile” will often appear almost interchangeably in otherwise similar sentences, and that means they’ll be placed nearby in the embedding. But “turnip” and “eagle” won’t tend to appear in otherwise similar sentences, so they’ll be placed far apart in the embedding.

But how does one actually implement something like this using neural nets? Let’s start by talking about embeddings not for words, but for images. We want to find some way to characterize images by lists of numbers in such a way that “images we consider similar” are assigned similar lists of numbers.

How do we tell if we should “consider images similar”? Well, if our images are, say, of handwritten digits we might “consider two images similar” if they are of the same digit. Earlier we discussed a neural net that was trained to recognize handwritten digits. And we can think of this neural net as being set up so that in its final output it puts images into 10 different bins, one for each digit.

But what if we “intercept” what’s going on inside the neural net before the final “it’s a ‘4’” decision is made? We might expect that inside the neural net there are numbers that characterize images as being “mostly 4-like but a bit 2-like” or some such. And the idea is to pick up such numbers to use as elements in an embedding.

So here’s the concept. Rather than directly trying to characterize “what image is near what other image”, we instead consider a well-defined task (in this case digit recognition) for which we can get explicit training data—then use the fact that in doing this task the neural net implicitly has to make what amount to “nearness decisions”. So instead of us ever explicitly having to talk about “nearness of images” we’re just talking about the concrete question of what digit an image represents, and then we’re “leaving it to the neural net” to implicitly determine what that implies about “nearness of images”.

So how in more detail does this work for the digit recognition network? We can think of the network as consisting of 11 successive layers, that we might summarize iconically like this (with activation functions shown as separate layers):

At the beginning we’re feeding into the first layer actual images, represented by 2D arrays of pixel values. And at the end—from the last layer—we’re getting out an array of 10 values, which we can think of saying “how certain” the network is that the image corresponds to each of the digits 0 through 9.

Feed in the image ![]() and the values of the neurons in that last layer are:

and the values of the neurons in that last layer are:

In other words, the neural net is by this point “incredibly certain” that this image is a 4—and to actually get the output “4” we just have to pick out the position of the neuron with the largest value.

But what if we look one step earlier? The very last operation in the network is a so-called softmax which tries to “force certainty”. But before that’s been applied the values of the neurons are:

The neuron representing “4” still has the highest numerical value. But there’s also information in the values of the other neurons. And we can expect that this list of numbers can in a sense be used to characterize the “essence” of the image—and thus to provide something we can use as an embedding. And so, for example, each of the 4’s here has a slightly different “signature” (or “feature embedding”)—all very different from the 8’s:

Here we’re essentially using 10 numbers to characterize our images. But it’s often better to use much more than that. And for example in our digit recognition network we can get an array of 500 numbers by tapping into the preceding layer. And this is probably a reasonable array to use as an “image embedding”.

If we want to make an explicit visualization of “image space” for handwritten digits we need to “reduce the dimension”, effectively by projecting the 500-dimensional vector we’ve got into, say, 3D space:

We’ve just talked about creating a characterization (and thus embedding) for images based effectively on identifying the similarity of images by determining whether (according to our training set) they correspond to the same handwritten digit. And we can do the same thing much more generally for images if we have a training set that identifies, say, which of 5000 common types of object (cat, dog, chair, …) each image is of. And in this way we can make an image embedding that’s “anchored” by our identification of common objects, but then “generalizes around that” according to the behavior of the neural net. And the point is that insofar as that behavior aligns with how we humans perceive and interpret images, this will end up being an embedding that “seems right to us”, and is useful in practice in doing “human-judgement-like” tasks.

OK, so how do we follow the same kind of approach to find embeddings for words? The key is to start from a task about words for which we can readily do training. And the standard such task is “word prediction”. Imagine we’re given “the ___ cat”. Based on a large corpus of text (say, the text content of the web), what are the probabilities for different words that might “fill in the blank”? Or, alternatively, given “___ black ___” what are the probabilities for different “flanking words”?

How do we set this problem up for a neural net? Ultimately we have to formulate everything in terms of numbers. And one way to do this is just to assign a unique number to each of the 50,000 or so common words in English. So, for example, “the” might be 914, and “ cat” (with a space before it) might be 3542. (And these are the actual numbers used by GPT-2.) So for the “the ___ cat” problem, our input might be {914, 3542}. What should the output be like? Well, it should be a list of 50,000 or so numbers that effectively give the probabilities for each of the possible “fill-in” words. And once again, to find an embedding, we want to “intercept” the “insides” of the neural net just before it “reaches its conclusion”—and then pick up the list of numbers that occur there, and that we can think of as “characterizing each word”.

OK, so what do those characterizations look like? Over the past 10 years there’ve been a sequence of different systems developed (word2vec, GloVe, BERT, GPT, …), each based on a different neural net approach. But ultimately all of them take words and characterize them by lists of hundreds to thousands of numbers.

In their raw form, these “embedding vectors” are quite uninformative. For example, here’s what GPT-2 produces as the raw embedding vectors for three specific words:

If we do things like measure distances between these vectors, then we can find things like “nearnesses” of words. Later we’ll discuss in more detail what we might consider the “cognitive” significance of such embeddings. But for now the main point is that we have a way to usefully turn words into “neural-net-friendly” collections of numbers.

But actually we can go further than just characterizing words by collections of numbers; we can also do this for sequences of words, or indeed whole blocks of text. And inside ChatGPT that’s how it’s dealing with things. It takes the text it’s got so far, and generates an embedding vector to represent it. Then its goal is to find the probabilities for different words that might occur next. And it represents its answer for this as a list of numbers that essentially give the probabilities for each of the 50,000 or so possible words.

(Strictly, ChatGPT does not deal with words, but rather with “tokens”—convenient linguistic units that might be whole words, or might just be pieces like “pre” or “ing” or “ized”. Working with tokens makes it easier for ChatGPT to handle rare, compound and non-English words, and, sometimes, for better or worse, to invent new words.)

Inside ChatGPT

OK, so we’re finally ready to discuss what’s inside ChatGPT. And, yes, ultimately, it’s a giant neural net—currently a version of the so-called GPT-3 network with 175 billion weights. In many ways this is a neural net very much like the other ones we’ve discussed. But it’s a neural net that’s particularly set up for dealing with language. And its most notable feature is a piece of neural net architecture called a “transformer”.

In the first neural nets we discussed above, every neuron at any given layer was basically connected (at least with some weight) to every neuron on the layer before. But this kind of fully connected network is (presumably) overkill if one’s working with data that has particular, known structure. And thus, for example, in the early stages of dealing with images, it’s typical to use so-called convolutional neural nets (“convnets”) in which neurons are effectively laid out on a grid analogous to the pixels in the image—and connected only to neurons nearby on the grid.

The idea of transformers is to do something at least somewhat similar for sequences of tokens that make up a piece of text. But instead of just defining a fixed region in the sequence over which there can be connections, transformers instead introduce the notion of “attention”—and the idea of “paying attention” more to some parts of the sequence than others. Maybe one day it’ll make sense to just start a generic neural net and do all customization through training. But at least as of now it seems to be critical in practice to “modularize” things—as transformers do, and probably as our brains also do.

OK, so what does ChatGPT (or, rather, the GPT-3 network on which it’s based) actually do? Recall that its overall goal is to continue text in a “reasonable” way, based on what it’s seen from the training it’s had (which consists in looking at billions of pages of text from the web, etc.) So at any given point, it’s got a certain amount of text—and its goal is to come up with an appropriate choice for the next token to add.

It operates in three basic stages. First, it takes the sequence of tokens that corresponds to the text so far, and finds an embedding (i.e. an array of numbers) that represents these. Then it operates on this embedding—in a “standard neural net way”, with values “rippling through” successive layers in a network—to produce a new embedding (i.e. a new array of numbers). It then takes the last part of this array and generates from it an array of about 50,000 values that turn into probabilities for different possible next tokens. (And, yes, it so happens that there are about the same number of tokens used as there are common words in English, though only about 3000 of the tokens are whole words, and the rest are fragments.)

A critical point is that every part of this pipeline is implemented by a neural network, whose weights are determined by end-to-end training of the network. In other words, in effect nothing except the overall architecture is “explicitly engineered”; everything is just “learned” from training data.

There are, however, plenty of details in the way the architecture is set up—reflecting all sorts of experience and neural net lore. And—even though this is definitely going into the weeds—I think it’s useful to talk about some of those details, not least to get a sense of just what goes into building something like ChatGPT.

First comes the embedding module. Here’s a schematic Wolfram Language representation for it for GPT-2:

The input is a vector of n tokens (represented as in the previous section by integers from 1 to about 50,000). Each of these tokens is converted (by a single-layer neural net) into an embedding vector (of length 768 for GPT-2 and 12,288 for ChatGPT’s GPT-3). Meanwhile, there’s a “secondary pathway” that takes the sequence of (integer) positions for the tokens, and from these integers creates another embedding vector. And finally the embedding vectors from the token value and the token position are added together—to produce the final sequence of embedding vectors from the embedding module.

Why does one just add the token-value and token-position embedding vectors together? I don’t think there’s any particular science to this. It’s just that various different things have been tried, and this is one that seems to work. And it’s part of the lore of neural nets that—in some sense—so long as the setup one has is “roughly right” it’s usually possible to home in on details just by doing sufficient training, without ever really needing to “understand at an engineering level” quite how the neural net has ended up configuring itself.

Here’s what the embedding module does, operating on the string hello hello hello hello hello hello hello hello hello hello bye bye bye bye bye bye bye bye bye bye:

The elements of the embedding vector for each token are shown down the page, and across the page we see first a run of “hello” embeddings, followed by a run of “bye” ones. The second array above is the positional embedding—with its somewhat-random-looking structure being just what “happened to be learned” (in this case in GPT-2).

OK, so after the embedding module comes the “main event” of the transformer: a sequence of so-called “attention blocks” (12 for GPT-2, 96 for ChatGPT’s GPT-3). It’s all pretty complicated—and reminiscent of typical large hard-to-understand engineering systems, or, for that matter, biological systems. But anyway, here’s a schematic representation of a single “attention block” (for GPT-2):

Within each such attention block there are a collection of “attention heads” (12 for GPT-2, 96 for ChatGPT’s GPT-3)—each of which operates independently on different chunks of values in the embedding vector. (And, yes, we don’t know any particular reason why it’s a good idea to split up the embedding vector, or what the different parts of it “mean”; this is just one of those things that’s been “found to work”.)

OK, so what do the attention heads do? Basically they’re a way of “looking back” in the sequence of tokens (i.e. in the text produced so far), and “packaging up the past” in a form that’s useful for finding the next token. In the first section above we talked about using 2-gram probabilities to pick words based on their immediate predecessors. What the “attention” mechanism in transformers does is to allow “attention to” even much earlier words—thus potentially capturing the way, say, verbs can refer to nouns that appear many words before them in a sentence.

At a more detailed level, what an attention head does is to recombine chunks in the embedding vectors associated with different tokens, with certain weights. And so, for example, the 12 attention heads in the first attention block (in GPT-2) have the following (“look-back-all-the-way-to-the-beginning-of-the-sequence-of-tokens”) patterns of “recombination weights” for the “hello, bye” string above:

After being processed by the attention heads, the resulting “re-weighted embedding vector” (of length 768 for GPT-2 and length 12,288 for ChatGPT’s GPT-3) is passed through a standard “fully connected” neural net layer. It’s hard to get a handle on what this layer is doing. But here’s a plot of the 768×768 matrix of weights it’s using (here for GPT-2):

Taking 64×64 moving averages, some (random-walk-ish) structure begins to emerge:

What determines this structure? Ultimately it’s presumably some “neural net encoding” of features of human language. But as of now, what those features might be is quite unknown. In effect, we’re “opening up the brain of ChatGPT” (or at least GPT-2) and discovering, yes, it’s complicated in there, and we don’t understand it—even though in the end it’s producing recognizable human language.

OK, so after going through one attention block, we’ve got a new embedding vector—which is then successively passed through additional attention blocks (a total of 12 for GPT-2; 96 for GPT-3). Each attention block has its own particular pattern of “attention” and “fully connected” weights. Here for GPT-2 are the sequence of attention weights for the “hello, bye” input, for the first attention head:

And here are the (moving-averaged) “matrices” for the fully connected layers:

Curiously, even though these “matrices of weights” in different attention blocks look quite similar, the distributions of the sizes of weights can be somewhat different (and are not always Gaussian):

So after going through all these attention blocks what is the net effect of the transformer? Essentially it’s to transform the original collection of embeddings for the sequence of tokens to a final collection. And the particular way ChatGPT works is then to pick up the last embedding in this collection, and “decode” it to produce a list of probabilities for what token should come next.

So that’s in outline what’s inside ChatGPT. It may seem complicated (not least because of its many inevitably somewhat arbitrary “engineering choices”), but actually the ultimate elements involved are remarkably simple. Because in the end what we’re dealing with is just a neural net made of “artificial neurons”, each doing the simple operation of taking a collection of numerical inputs, and then combining them with certain weights.

The original input to ChatGPT is an array of numbers (the embedding vectors for the tokens so far), and what happens when ChatGPT “runs” to produce a new token is just that these numbers “ripple through” the layers of the neural net, with each neuron “doing its thing” and passing the result to neurons on the next layer. There’s no looping or “going back”. Everything just “feeds forward” through the network.

It’s a very different setup from a typical computational system—like a Turing machine—in which results are repeatedly “reprocessed” by the same computational elements. Here—at least in generating a given token of output—each computational element (i.e. neuron) is used only once.

But there is in a sense still an “outer loop” that reuses computational elements even in ChatGPT. Because when ChatGPT is going to generate a new token, it always “reads” (i.e. takes as input) the whole sequence of tokens that come before it, including tokens that ChatGPT itself has “written” previously. And we can think of this setup as meaning that ChatGPT does—at least at its outermost level—involve a “feedback loop”, albeit one in which every iteration is explicitly visible as a token that appears in the text that it generates.

But let’s come back to the core of ChatGPT: the neural net that’s being repeatedly used to generate each token. At some level it’s very simple: a whole collection of identical artificial neurons. And some parts of the network just consist of (“fully connected”) layers of neurons in which every neuron on a given layer is connected (with some weight) to every neuron on the layer before. But particularly with its transformer architecture, ChatGPT has parts with more structure, in which only specific neurons on different layers are connected. (Of course, one could still say that “all neurons are connected”—but some just have zero weight.)

In addition, there are aspects of the neural net in ChatGPT that aren’t most naturally thought of as just consisting of “homogeneous” layers. And for example—as the iconic summary above indicates—inside an attention block there are places where “multiple copies are made” of incoming data, each then going through a different “processing path”, potentially involving a different number of layers, and only later recombining. But while this may be a convenient representation of what’s going on, it’s always at least in principle possible to think of “densely filling in” layers, but just having some weights be zero.

If one looks at the longest path through ChatGPT, there are about 400 (core) layers involved—in some ways not a huge number. But there are millions of neurons—with a total of 175 billion connections and therefore 175 billion weights. And one thing to realize is that every time ChatGPT generates a new token, it has to do a calculation involving every single one of these weights. Implementationally these calculations can be somewhat organized “by layer” into highly parallel array operations that can conveniently be done on GPUs. But for each token that’s produced, there still have to be 175 billion calculations done (and in the end a bit more)—so that, yes, it’s not surprising that it can take a while to generate a long piece of text with ChatGPT.

But in the end, the remarkable thing is that all these operations—individually as simple as they are—can somehow together manage to do such a good “human-like” job of generating text. It has to be emphasized again that (at least so far as we know) there’s no “ultimate theoretical reason” why anything like this should work. And in fact, as we’ll discuss, I think we have to view this as a—potentially surprising—scientific discovery: that somehow in a neural net like ChatGPT’s it’s possible to capture the essence of what human brains manage to do in generating language.

The Training of ChatGPT

OK, so we’ve now given an outline of how ChatGPT works once it’s set up. But how did it get set up? How were all those 175 billion weights in its neural net determined? Basically they’re the result of very large-scale training, based on a huge corpus of text—on the web, in books, etc.—written by humans. As we’ve said, even given all that training data, it’s certainly not obvious that a neural net would be able to successfully produce “human-like” text. And, once again, there seem to be detailed pieces of engineering needed to make that happen. But the big surprise—and discovery—of ChatGPT is that it’s possible at all. And that—in effect—a neural net with “just” 175 billion weights can make a “reasonable model” of text humans write.

In modern times, there’s lots of text written by humans that’s out there in digital form. The public web has at least several billion human-written pages, with altogether perhaps a trillion words of text. And if one includes non-public webpages, the numbers might be at least 100 times larger. So far, more than 5 million digitized books have been made available (out of 100 million or so that have ever been published), giving another 100 billion or so words of text. And that’s not even mentioning text derived from speech in videos, etc. (As a personal comparison, my total lifetime output of published material has been a bit under 3 million words, and over the past 30 years I’ve written about 15 million words of email, and altogether typed perhaps 50 million words—and in just the past couple of years I’ve spoken more than 10 million words on livestreams. And, yes, I’ll train a bot from all of that.)

But, OK, given all this data, how does one train a neural net from it? The basic process is very much as we discussed it in the simple examples above. You present a batch of examples, and then you adjust the weights in the network to minimize the error (“loss”) that the network makes on those examples. The main thing that’s expensive about “back propagating” from the error is that each time you do this, every weight in the network will typically change at least a tiny bit, and there are just a lot of weights to deal with. (The actual “back computation” is typically only a small constant factor harder than the forward one.)

With modern GPU hardware, it’s straightforward to compute the results from batches of thousands of examples in parallel. But when it comes to actually updating the weights in the neural net, current methods require one to do this basically batch by batch. (And, yes, this is probably where actual brains—with their combined computation and memory elements—have, for now, at least an architectural advantage.)

Even in the seemingly simple cases of learning numerical functions that we discussed earlier, we found we often had to use millions of examples to successfully train a network, at least from scratch. So how many examples does this mean we’ll need in order to train a “human-like language” model? There doesn’t seem to be any fundamental “theoretical” way to know. But in practice ChatGPT was successfully trained on a few hundred billion words of text.

Some of the text it was fed several times, some of it only once. But somehow it “got what it needed” from the text it saw. But given this volume of text to learn from, how large a network should it require to “learn it well”? Again, we don’t yet have a fundamental theoretical way to say. Ultimately—as we’ll discuss further below—there’s presumably a certain “total algorithmic content” to human language and what humans typically say with it. But the next question is how efficient a neural net will be at implementing a model based on that algorithmic content. And again we don’t know—although the success of ChatGPT suggests it’s reasonably efficient.

And in the end we can just note that ChatGPT does what it does using a couple hundred billion weights—comparable in number to the total number of words (or tokens) of training data it’s been given. In some ways it’s perhaps surprising (though empirically observed also in smaller analogs of ChatGPT) that the “size of the network” that seems to work well is so comparable to the “size of the training data”. After all, it’s certainly not that somehow “inside ChatGPT” all that text from the web and books and so on is “directly stored”. Because what’s actually inside ChatGPT are a bunch of numbers—with a bit less than 10 digits of precision—that are some kind of distributed encoding of the aggregate structure of all that text.