Metaengineering and Laws of Innovation

Things are invented. Things are discovered. And somehow there’s an arc of progress that’s formed. But are there what amount to “laws of innovation” that govern that arc of progress?

There are some exponential and other laws that purport to at least measure overall quantitative aspects of progress (number of transistors on a chip; number of papers published in a year; etc.). But what about all the disparate innovations that make up the arc of progress? Do we have a systematic way to study those?

We can look at the plans for different kinds of bicycles or rockets or microprocessors. And over the course of years we’ll see the results of successive innovations. But most of the time those innovations won’t stay within one particular domain—say shapes of bicycle frames. Rather they’ll keep on pulling in innovations from other domains—say, new materials or new manufacturing techniques. But if we want to get closer to the study of the pure phenomenon of innovation we need a case where—preferably over a long period of time—everything that happens can be described in a uniform way within a single narrowly defined framework.

Well, some time ago I realized that, actually, yes, there is such a case—and I’ve even personally been following it for about half a century. It’s the effort to build “engineering” structures within the Game of Life cellular automaton. They might serve as clocks, wires, logic gates, or things that generate digits of π. But the point is that they’re all just patterns of bits. So when we talk about innovation in this case, we’re talking about the rather pure question of how patterns of bits get invented, or discovered.

As a long-time serious researcher of the science of cellular automata (and of what they generically do), I must say I’ve long been frustrated by how specific, whimsical and “non-scientific” the things people do with the Game of Life have often seemed to me to be. But what I now realize is that all that detail and all that hard work have now created what amounts to a unique dataset of engineering innovation. And my goal here is to do what one can call “metaengineering”—and to study in effect what happened in that process of engineering over the nearly six decades since the Game of Life was invented.

We’ll see in rather pure form many phenomena that are at least anecdotally familiar from our overall experience of progress and innovation. Most of the time, the first step is to identify an objective: some purpose one can describe and wants to achieve. (Much more rarely, one instead observes something that happens, then realizes there’s a way one can meaningfully make use of it.) But starting from an objective, one either takes components one has, and puts human effort into arranging them to “invent” something that will achieve the objective—or in effect (usually at least somewhat systematically, and automatically) one searches to try to “discover” new ways to achieve the objective.

As we explore what’s been done with the Game of Life we’ll see occasional sudden advances—together with much larger amounts of incremental progress. We’ll see towers of technology being built, and we’ll see old, rather simple technology being used to achieve new objectives. But most of all, we’ll see an interplay between what gets discovered by searching possibilities—and what gets invented by explicit human effort.

The Principle of Computational Equivalence implies that there is, in a sense, infinite richness to what a computational system like the Game of Life can ultimately do—and it’s the role of science to explore this richness in all its breadth. But when it comes to engineering and technology the crucial question is what we choose to make the system do—and what paths we follow to get there. Inevitably, some of this is determined by the underlying computational structure of the system. But much of it is a reflection of how we, as humans, do things, and the patterns of choices we make. And that’s what we’ll be able to study—at quite large scale—by looking at the nearly six decades of work on the Game of Life.

How similar are the results of such “purposeful engineering” to the results of “blind” adaptive evolution of the kind that occurs in biology? I recently explored adaptive evolution (as it happens, using cellular automata as a model) and saw that it can routinely deliver what seem like “sequences of new ideas”. But now in the example of the Game of Life we have what we can explicitly identify as “sequences of new ideas”. And so we’re in a position to compare the results of human effort (aided, in many cases, by systematic search) with what we can “automatically” do by the algorithmic process of adaptive evolution.

In the end, we can think of the set of things that we can in principle engineer as being laid out in a kind of “metaengineering space”, much as we can think of mathematical theorems we can prove as being laid out in metamathematical space. In the mathematical case (notwithstanding some of my own work) the vast majority of theorems have historically been found purely by human effort. But, as we’ll see below, in Game-of-Life engineering it’s been a mixture of human effort and fairly automated exploration of metaengineering space. Though—much like in traditional mathematics—we’ve still in a sense always only pursuing objectives we’ve already conceptualized. And in this way what we’re doing is very different from what I’ve done for so long in studying the science (or, as I would now say, the ruliology) of what computational systems like cellular automata (of which the Game of Life is an example) do “in the wild”, when they’re unconstrained by objectives we’re trying to achieve with them.

The Nature of the Game of Life

Here’s a typical example of what it looks like to run the Game of Life:

There’s a lot of complicated—and hard to understand—stuff going on here. But there are still some recognizable structures—like the “blinkers” that alternate on successive steps

and the “gliders” that steadily move across the screen:

Seeing these structures might make one think that one should be able to “do engineering” in the Game of Life, setting up patterns that can ultimately do all sorts of things. And indeed our main subject here is the actual development of such engineering over the past nearly six decades since the introduction of the Game of Life.

What we’ll be concentrating on is essentially the “technology” of the Game of Life: how we take the “raw material” that the Game of Life provides, and make from it “meaningful engineering structures”.

But what about the science of the Game of Life? What can we say about what the Game of Life “naturally does”, independent of “useful” structures we create in it? The vast majority of the effort that’s been put into the Game of Life over the past half century hasn’t been about this. But this type of fundamental question is central to what one asks in what I now call ruliology—a kind of science that I’ve been energetically pursuing since the early 1980s.

Ruliology looks in general at classes of systems, rather then at the kind of specifics that have typically been explored in the Game of Life. And within ruliology, the Game of Life is in a sense nothing special; it’s just one of many “class 4” 2D cellular automaton (in my numbering scheme, it’s the 2-color 9-neighbor cellular automaton with outer totalistic code 224).

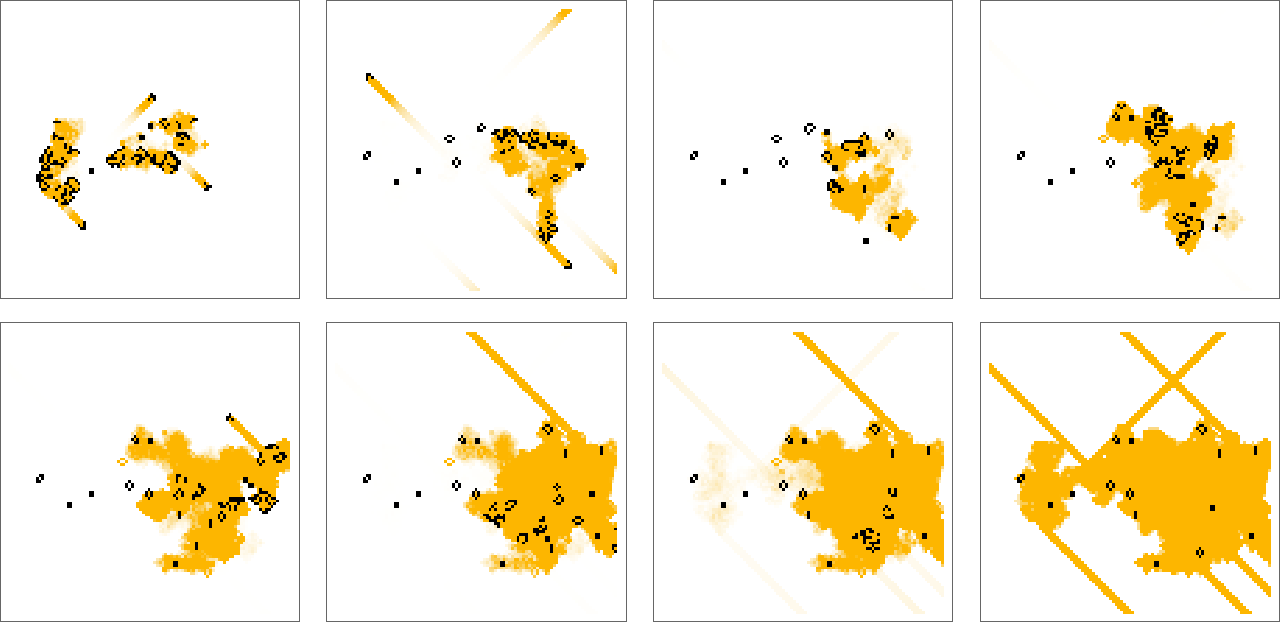

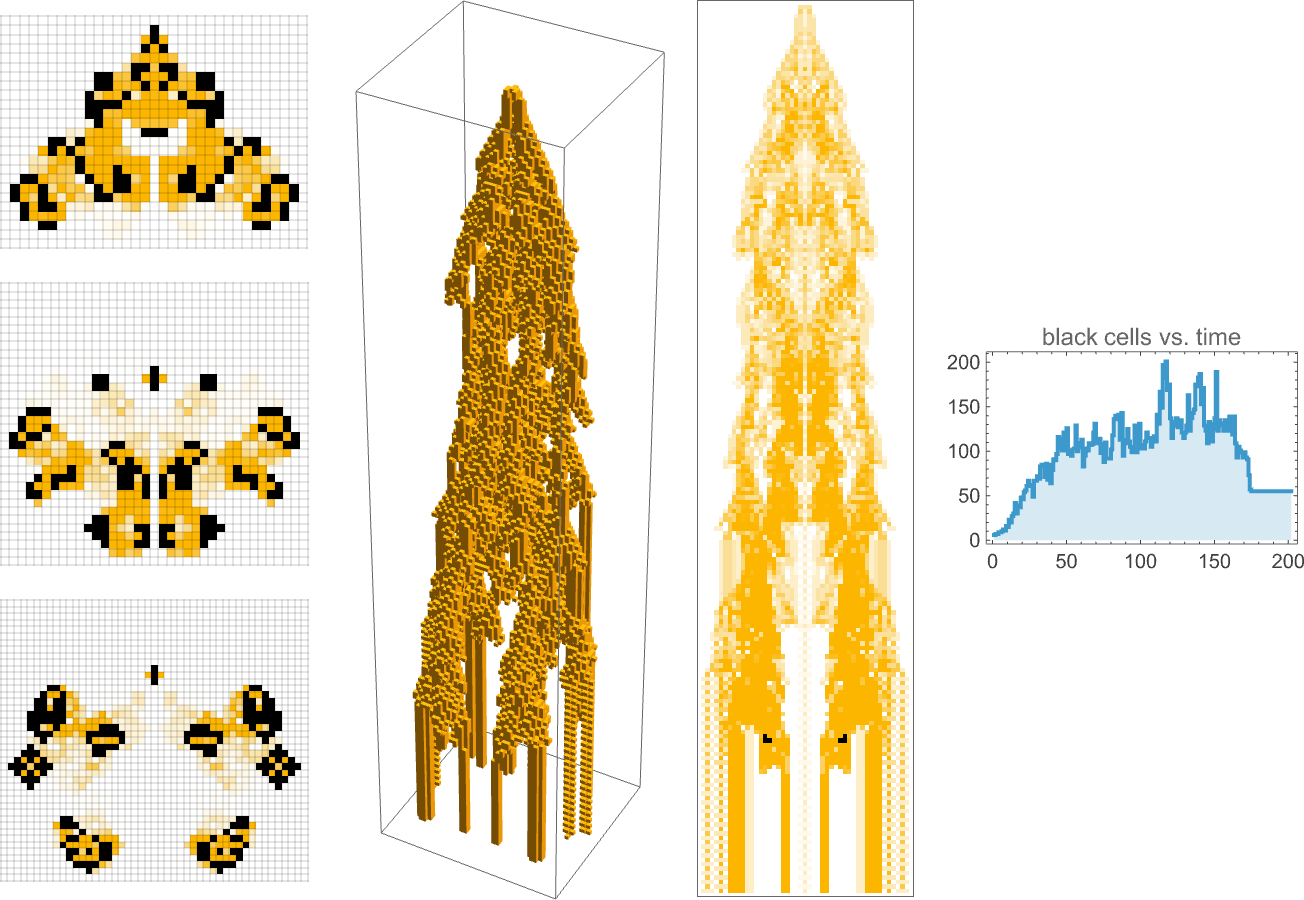

My own investigations of cellular automata have particularly focused in 1D than 2D examples. And I think that’s been crucial to many of the scientific discoveries I’ve made. Because somehow one learns so much more by being able to see at a glance the history of a system, rather than just seeing frames in a video go by. With a class 4 2D rule like the Game of Life, one can begin to approach this by including “trails” of what’s previously happened, and we’ll often use this kind of visualization in what follows:

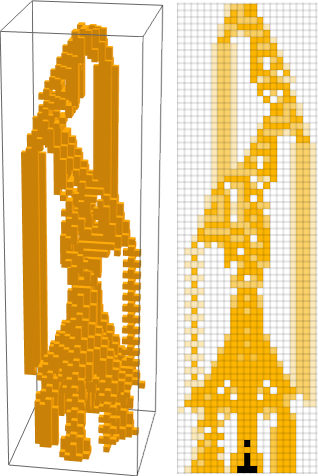

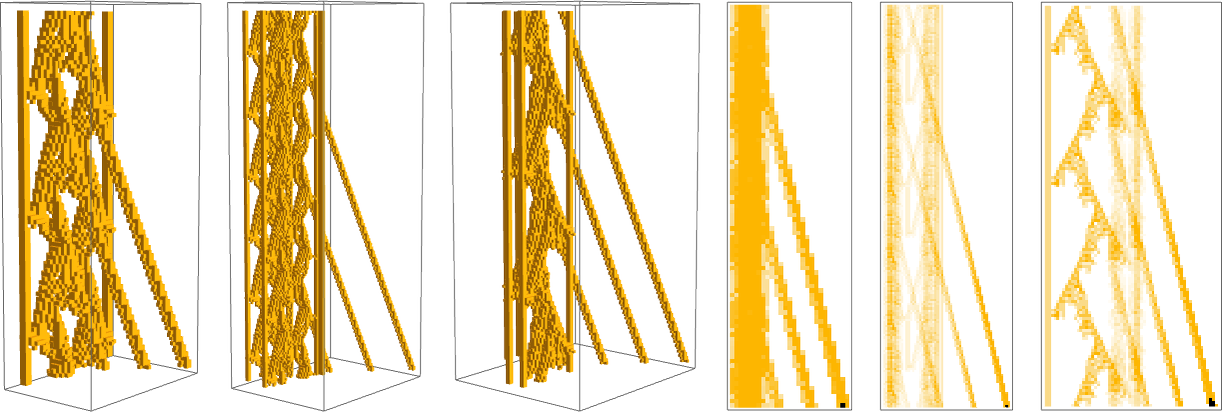

We can get a more complete view of history by looking at the whole (2+1)-dimensional “spacetime history”—though then we’re confronted with 3D forms that are often somewhat difficult for our human visual system to parse:

But taking a slice through this 3D form we get “silhouette” pictures that turn out to look remarkably similar to what I generated in large quantities starting in the early 1980s across many 1D cellular automata:

Such pictures—with their complex forms—highlight the computational irreducibility that’s close at hand even in the Game of Life. And indeed it’s the presence of such computational irreducibility that ultimately makes possible the richness of engineering that can be done in the Game of Life. But in actually doing that engineering—and in setting up structures and processes that behave in understandable and “technologically useful” ways—we need to keep the computational irreducibility “bottled up”. And in the end, we can think of the path of engineering innovation in the Game of Life as like an effort to navigate through an ocean of computational irreducibility, finding “islands of reducibility” that achieve the purposes we want.

What’s Been Made in the Game of Life?

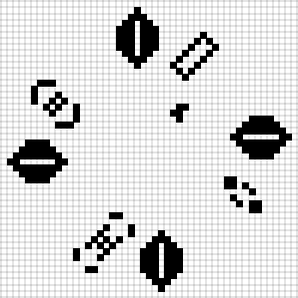

Most of the structures of “engineering interest” in the Game of Life are somehow persistent. The simplest are structures that just remain constant, some small examples being:

And, yes, structures in the Game of Life have been given all sorts of (usually whimsical) names, which I’ll use here. (And, in that vein, structures in the Game of Life that remain constant are normally called “still lifes”.)

Beyond structures that just remain constant, there are “oscillators” that produce periodic patterns:

We’ll be discussing oscillators at much greater length below, but here are a few examples (where now we’re including a visualization that shows “trails”):

Next in our inventory of classes of structures come “gliders” (or in general “spaceships”): structures that repeat periodically but move when they do so. A classic example is the basic glider, which takes on the same form every 4 steps—after moving 1 cell horizontally and 1 cell vertically:

Here are a few small examples of such “spaceship”-style structures:

Still lifes, oscillators and spaceships are most of what one sees in the “ash” that survives from typical random initial conditions. And for example the end result (after 1103 steps) from the evolution we saw in the previous section consists of:

The structures we’ve seen so far were all found not long after the Game of Life was invented; indeed, pretty much as soon it was simulated on a computer. But one feature that they all share is that they don’t systematically grow; they always return to the same number of black cells. And so one of the early surprises (in 1970) was the discovery of a “glider gun” that shoots out a glider every 30 steps forever:

Something that gives a sense of progress that’s been made in Game-of-Life “technology” is that a “more efficient” glider gun—with period 15—was discovered, but only in 2024, 54 years after the previous one:

Another kind of structure that was quickly discovered in the early history of the Game of Life is a “puffer”—a “spaceship” that “leaves debris behind” (in this case every 128 steps):

But given these kinds of “components”, what can one build? Something constructed very early was the “breeder”, that uses streams of gliders to create glider guns, that themselves then generate streams of gliders:

The original pattern covers about a quarter million cells (with 4060 being black). Running it for 1000 steps we see it builds up a triangle containing a quadratically increasing number of gliders:

OK, but knowing that it’s in principle possible to “fill a growing region of space”, is there a more efficient way to do it? The surprisingly simple answer, as discovered in 1993, is yes:

So what other kinds of things can be built in the Game of Life? Lots—even from the simple structures we’ve seen so far. For example, here’s a pattern that was constructed to compute the primes

emitting a “lightweight spaceship” at step 100 + 120n only if n is prime. It’s a little more obvious how this works when it’s viewed “in spacetime”; in effect it’s running a sieve in which all multiples of all numbers are instantiated as streams of gliders, which knock out spaceships generated at non-prime positions:

If we look at the original pattern here, it’s just made up of a collection of rather simple structures:

And indeed structures like these have been used to build all sorts of things, including for example Turing machine emulators—and also an emulator for the Game of Life itself, with this 499×499 pattern corresponding to a single emulated Life cell:

Both these last two patterns were constructed in the 1990s—from components that had been known since the early 1970s. And—as we can see—they’re large (and complicated). But do they need to be so large? One of the lessons of the Principle of Computational Equivalence is that in the computational universe there’s almost always a way to “do just as much, but with much less”. And indeed in the Game of Life many, many discoveries along these lines have been made in the past few decades.

As we’ll see, often (but not always) these discoveries built on “new devices” and “new mechanisms” that were identified in the intervening years. A long series of such “devices” and “mechanisms” involved handling “signals” associated with streams of gliders. For example, the “glider pusher” (from 1993) has the somewhat subtle (but useful) effect of “pushing” a glider by one cell when it goes past:

Another example (actually already known in 1971, and based on the period-15 “pentadecathlon” oscillator) is a glider reflector:

But a feature of this glider pusher and glider reflector is that they work only when both the glider and the stationary object are in a particular phase with respect to their periods. And this makes it very tricky to build larger structures out of these that operate correctly (and in many cases it wouldn’t be possible but for the commensurability of the period 30 of the original glider gun, and the period 15 of the glider reflector).

Could glider pushing and glider reflection be done more robustly? The answer turns out to be yes. Though it wasn’t until 2020 that the “bandersnatch” was created—a completely static structure that “pushes” gliders independent of their phase:

Meanwhile, in 2013 the “snark” had been created—which served as a phase-independent glider reflector:

One theme—to which we’ll return later—is that after certain functionality was first built in the Game of Life, there followed many “optimizations”, achieving that functionality more robustly, with smaller patterns, etc. An important methodology has revolved around so-called “hasslers”, which in effect allow one to “mine” small pieces of computational irreducibility, by providing “harnesses” that “rein in” behavior, typically returning patterns to their original states after they’ve done what one wants them to do.

So, for example, here’s a hassler (found, as it happens just on February 8, 2025!) that “harnesses” the first pattern we looked at above (that didn’t stabilize for 1103 steps) into an oscillator with period 80:

And based on this (indeed, later that same day) the most-compact-ever “spaceship gun” was constructed from this:

The Arc of Progress

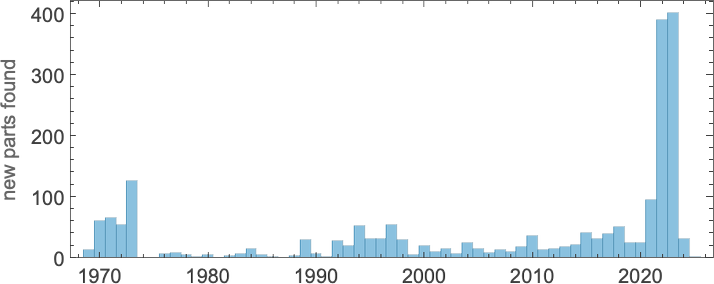

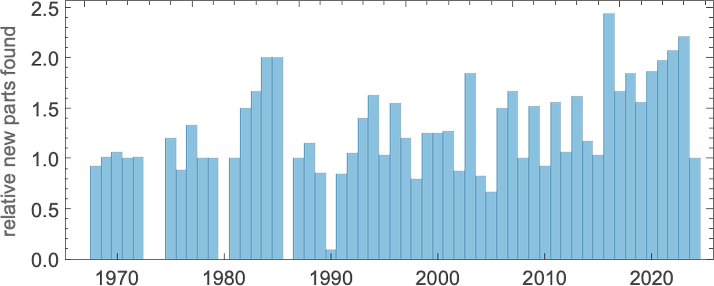

We’ve talked about some of what it’s been possible to build in the Game of Life over the years. Now I want to talk about how that happened, or, in other words, the “arc of progress” in the Game of Life. And as a first indication of this, we can plot the number of new Life structures that have been identified each year (or, more specifically, the number of structures deemed significant enough to name, and to record in the LifeWiki database or its predecessors):

There’s an immediate impression of several waves of activity. And we can break this down into activity around various common categories of structures:

For oscillators we see fairly continuous activity for five decades, but with rapid acceleration recently. For “spaceships” and “guns” we see a long dry spell from the early 1970s to the 1990s, followed by fairly consistent activity since. And for conduits and reflectors we see almost nothing until sudden peaks of activity, in the mid-1990s and mid-2010s respectively.

But what was actually done to find all these structures? There have basically been two methods: construction and search. Construction is a story of “explicit engineering”—and of using human thought to build up what one wants. Search, on the other hand, is a story of automation—and of taking algorithmically generated (usually large) collections of possible patterns, and testing them to find ones that do what one wants. Particularly in more recent times it’s also become common to interleave these methods, for example using construction to build a framework, and then using search to find specific patterns that implement some feature of that framework.

When one uses construction, it’s like “inventing” a structure, and when one uses search, it’s like “discovering” it. So how much of each is being done in practice? Text mining descriptions of recently recorded structures the result is as follows—suggesting that, at least in recent times, search (i.e. “discovery”) has become the dominant methodology for finding new structures:

When the Game of Life was being invented, it wasn’t long before it was being run on computers—and people were trying to classify the things it could do. Still lifes and simple oscillators showed up immediately. And then—evolving from the ![]() (“R pentomino”) initial condition that we used at the beginning here—after 69 steps something unexpected showed up. In between complicated behavior that was hard to describe was a simple free-standing structure that just systematically moved—a “glider”:

(“R pentomino”) initial condition that we used at the beginning here—after 69 steps something unexpected showed up. In between complicated behavior that was hard to describe was a simple free-standing structure that just systematically moved—a “glider”:

Some other moving structures (dubbed “spaceships”) were also observed. But the question arose: could there be a structure that would somehow systematically grow forever? To find it involved a mixture of “discovery” and “invention”. In running from the ![]() (“R pentomino”) initial condition lots of things happen. But at step 785 it was noticed that there appeared the following structure:

(“R pentomino”) initial condition lots of things happen. But at step 785 it was noticed that there appeared the following structure:

For a while this structure (dubbed the “queen bee”) behaves in a fairly orderly way—producing two stable “beehive” structures (visible here as vertical columns). But then it “decays” into more complicated behavior:

But could this “discovered” behavior be “stabilized”? The answer was that, yes, if a “queen bee” was combined with two “blocks” it would just repeatedly “shuttle” back and forth:

What about two “queen bees”? Now whenever these collided there was a side effect: a glider was generated—with the result that the whole structure became a glider gun repeatedly producing gliders forever:

The glider gun was the first major example of a structure in the Game of Life that was found—at least in part—by construction. And within a year of it being found in November 1970, two more guns—with very similar methods of operation—had been found:

But then the well ran dry—and no further gun was found until 1990. Pretty much the same thing happened with spaceships: four were found in 1970, but no more were found until 1989. As we’ll discuss later, it was in a sense a quintessential story of computational irreducibility: there was no way to predict (or “construct”) what spaceships would exist; one just had to do the computation (i.e. search) to find out.

It was, however, easier to have incremental success with oscillators—and (as we’ll see) pretty much every year an oscillator with some new period was found, essentially always by search. Some periods were “long holdouts” (for example the first period-19 oscillator was found only in 2023), once again reflecting the effects of computational irreducibility.

Glider guns provided a source of “signals” for Life engineering. But what could one do with these signals? An important idea—that first showed up in the “breeder” in 1971—was “glider synthesis”: the concept that combinations of gliders could produce other structures. So, for example, it was found that three carefully-arranged gliders could generate a period-15 (“pentadecathlon”) oscillator:

It was also soon found that 8 gliders could make the original glider gun (the breeder made glider guns by a slightly more ornate method). And eventually there developed the conjecture that any structure that could be synthesized from gliders would need at most 15 gliders, carefully arranged at positions whose values effectively encoded the object to be constructed.

By the end of the 1970s a group of committed Life enthusiasts remained, but there was something of a feeling that “the low-hanging fruit had been picked”, and it wasn’t clear where to go next. But after a somewhat slow decade, work on the Game of Life picked up substantially towards the end of the 1980s. Perhaps my own work on cellular automata (and particularly the identification of class 4 cellular automata, of which the Game of Life is a 2D example) had something to do with. And no doubt it also helped that the fairly widespread availability of faster (“workstation class”) computers now made it possible for more people to do large-scale systematic searches. In addition, when the web arrived in the early 1990s it let people much more readily share results—and had the effect of greatly expanding and organizing the community of Life enthusiasts.

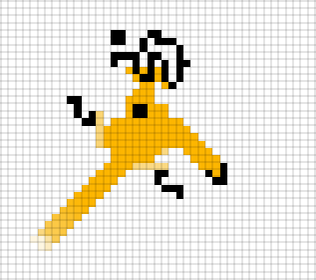

In the 1990s—along with more powerful searches that found new spaceships and guns—there was a burst of activity in constructing elaborate “machines” out of existing known structures. The idea was to start from a known type of “machine” (say a Turing machine), then to construct a Life implementation of it. The constructions were made particularly ornate by the need to make the phases of gliders, guns, etc. appropriately correspond. Needless to say, any Life configuration can be thought of as doing some computation. But the “machines” that were constructed were ones whose “purpose” and “functionality” was already well established in general computation, independent of the Game of Life.

If the 1990s saw a push towards “construction” in the Game of Life, the first decade of the 2000s saw a great expansion of search. Increasingly powerful cloud and distributed computing allowed “censuses” to be created of structures emerging from billions, then trillions of initial conditions. Mostly what was emphasized was finding new instances of existing categories of objects, like oscillators and spaceships. There were particular challenges, like (as we’ll discuss below) finding oscillators of any period (finally completely solved in 2023), or finding spaceships with different patterns of motion. Searches did yield what in censuses were usually called “objects with unusual growth”, but mostly these were not viewed as being of “engineering utility”, and so were not extensively studied (even though from the point of the “science of the Game of Life” they are, for example, perhaps the most revealing examples of computational irreducibility).

As had happened throughout the history of the Game of Life, some of the most notable new structures were created (sometimes over a long period of time) by a mixture of construction and search. For example, the “stably-reflect-gliders-without-regard-to-phase” snark—finally obtained in 2013—was the result of using parts of the (ultimately unstable) “simple-structures” construction from around 1998

and combining them with a hard-to-explain-why-it-works “still life” found by search:

Another example was the “Sir Robin knightship”—a spaceship that moves like a chess knight 2 cells down and 1 across. In 2017 a spaceship search found a structure that in 6 steps has many elements that make a knight move—but then subsequently “falls apart”:

But the next year a carefully orchestrated search was able to “find a tail” that “adds a fix” to this—and successfully produces a final “perfect knightship”:

By the way, the idea that one can take something that “almost works” and find a way to “fix it” is one that’s appeared repeatedly in the engineering history of the Game of Life. At the outset, it’s far from obvious that such a strategy would be viable. But the fact that it is seems to be similar to the story of why both biological evolution and machine learning are viable—which, as I’ve recently discussed, can be viewed as yet another consequence of the phenomenon of computational irreducibility.

One thing that’s happened many times in the history of the Game of Life is that at some point some category of structure—like a conduit—is identified, and named. But then it’s realized that actually there was something that could be seen as an instance of the same category of structure found much earlier, though without the clarity of the later instance, its significance wasn’t recognized. For example, in 1995 the “Herschel conduit” that moves a ![]() from one position to another (here in 64 steps) was discovered (by a search):

from one position to another (here in 64 steps) was discovered (by a search):

But then it was realized that—if looked at correctly—a similar phenomenon had actually already been seen in 1972, in the form of a structure that in effect takes ![]() if it is present, and “moves it” (in 28 steps) to a

if it is present, and “moves it” (in 28 steps) to a ![]() at a different position (albeit with a certain amount of “containable” other activity):

at a different position (albeit with a certain amount of “containable” other activity):

Looking at the plots above of the number of new structures found per year we see the largest peak after 2020. And, yes, it seems that during the pandemic people spent more time on the Game of Life—in particular trying to fill in tables of structures of particular types, for example, with each possible period.

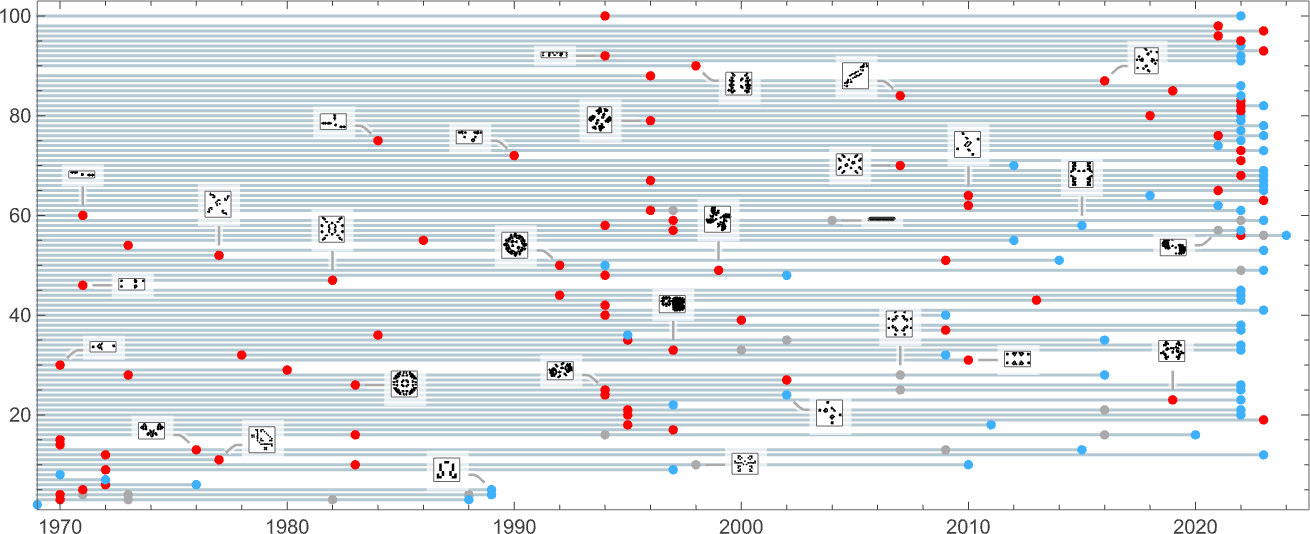

But what about the human side of engineering in the Game of Life? The activity brought in people from many different backgrounds. And particularly in earlier years, they often operated quite independently, and with very different methods (some not even using a computer). But if we look at all “recorded structures” we can look at how many structures in total different people contributed, and when they made these contributions:

Needless to say—given that we’re dealing with an almost-60-year span—different people tend to show up as active in different periods. Looking at everyone, there’s a roughly exponential distribution to the number of (named) structures they’ve contributed. (Though note that several of the top contributors shown here found parametrized collections of structures and then recorded many instances.)

The Example of Oscillators

As a first example of systematic “innovation history” in the Game of Life let’s talk about oscillators. Here are the periods of oscillators that were found up to 1980:

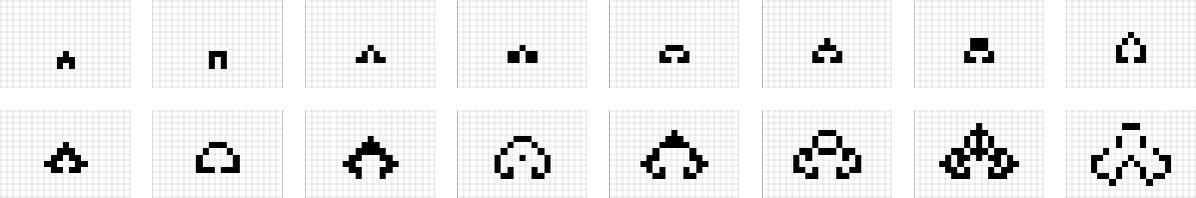

As of 1980, many periods were missing. But in fact all periods are possible—though it wasn’t until 2023 that they were all filled in:

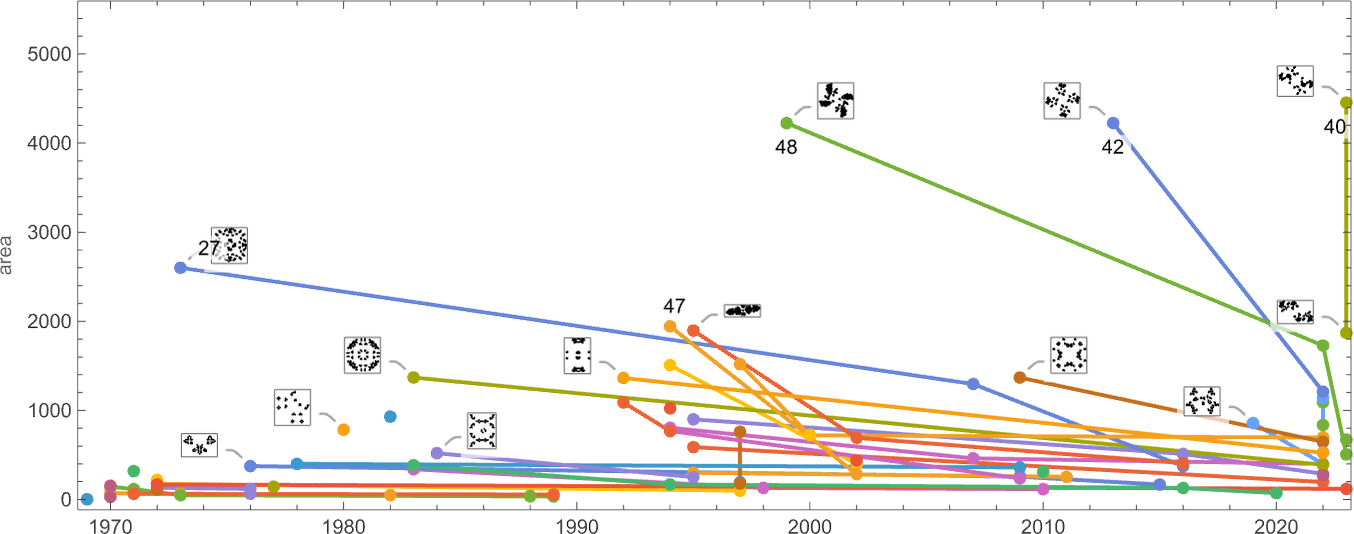

And if we plot the number of distinct periods (say below 60) found by a given year, we can get a first sense of the “arc of progress” in “oscillator technology” in the Game of Life:

Finding an oscillator of a given period is one thing. But how about the smallest oscillator of that period? We can be fairly certain that not all of these are known, even for periods below 30. But here’s a plot that shows when the progressive “smallest so far” oscillators were found for a given period (red indicates the first instance of a given period; blue the best result to date):

And here’s the corresponding plot for all periods up to 100:

But what about the actual reduction in size that’s achieved? Here’s a plot for each oscillator period showing the sequence of sizes found—in effect the “arc of engineering optimization” that’s achieved for that period:

So what are the actual patterns associated with these various oscillators? Here are some results (including timelines of when the patterns were found):

But how were these all found? The period-2 “blinker” was very obvious—showing up in evolution from almost any random initial condition. Some other oscillators were also easily found by looking at the evolution of particular, simple initial conditions. For example, a line of 10 black cells after 3 steps gives the period-15 “pentadecathlon”. Similarly, the period-3 “pulsar” emerges from a pair of length-5 blocks after 22 steps:

Many early oscillators were found by iterative experimentation, often starting with stable “still life” configurations, then perturbing them slightly, as in this period-4 case:

Another common strategy for finding oscillators (that we’ll discuss more below) was to take an “unstable” configuration, then to “stabilize” it by putting “robust” still lifes such as the “block” ![]() or the “eater”

or the “eater” ![]() around it—yielding results like:

around it—yielding results like:

For periods that can be formed as LCMs of smaller periods one “construction-oriented” strategy has been to take oscillators with appropriate smaller periods, and combine them, as in:

In general, many different strategies have been used, as indicated for example by the sequence of period-3 oscillators that have been recorded over the years (where “smallest-so-far” cases are highlighted):

By the mid-1990s oscillators of many periods had been found. But there were still holdouts, like period 19 and for example pretty much all periods between 61 and 70 (except, as it happens, 66). At the time, though, all sorts of complicated constructions—say of prime generators—were nevertheless being done. And in 1996 it was figured out that one could in effect always “build a machine” (using only structures that had already been found two decades earlier) that would serve as an oscillator of any (sufficiently large) period (here 67)—effectively by “sending a signal around a loop of appropriate size”:

But by the 2010s, with large numbers of fast computers becoming available, there was again an emphasis on pure random search. A handful of highly efficient programs were developed, that could be run on anyone’s machine. In a typical case, a search might consist of starting, say, from a trillion randomly chosen initial conditions (or “soups”), identifying new structures that emerge, then seeing whether these act, for example, as oscillators. Typically any new discovery was immediately reported in online forums—leading to variations of it being tried, and new follow-on results often being reported within hours or days.

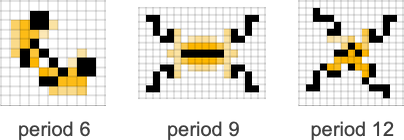

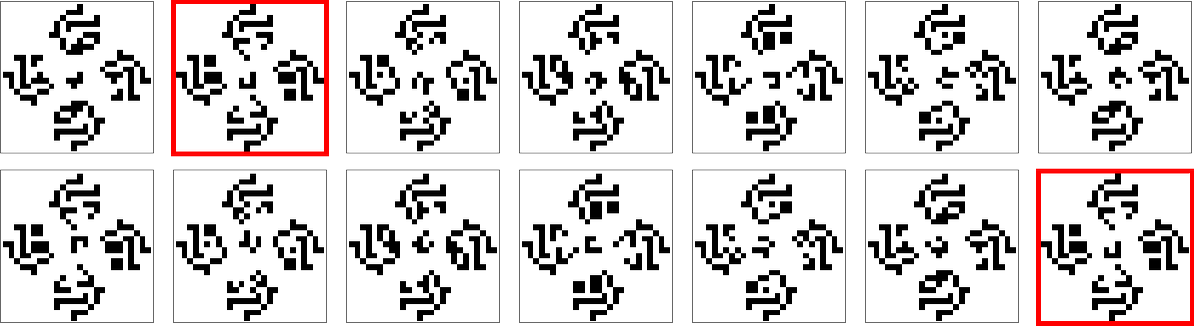

Many of the random searches started just from 16×16 regions of randomly chosen cells (or larger regions with symmetries imposed). And in a typical manifestation of computational irreducibility, many surprisingly small and “random-looking” (at least up to symmetries) results were found. So, for example, here’s the sequence of recorded period-16 oscillators with smaller-than-before cases highlighted:

Up through the 1990s results were typically found by a mixture of construction and small-scale search. But in 2016, results from large-scale random searches (sometimes symmetrical, sometimes not) started to appear.

The contrast between construction and search could be dramatic, like here for period 57:

One might wonder whether there could actually be a systematic, purely algorithmic way to find, say, possible oscillators of a given period. And indeed for one-dimensional cellular automata (as I noted in 1984), it turns out that there is. Say one considers blocks of cells of width w. Which block can follow which other is determined by a de Bruijn graph, or equivalently, a finite state machine. If one is going to have a pattern with period p, all blocks that appear in it must also be periodic with period p. But such blocks just form a subgraph of the overall de Bruijn graph, or equivalently, form another, smaller, finite state machine. And then all patterns with period p must correspond to paths through this subgraph. But how long are the blocks one has to consider?

In 1D cellular automata, it turns out that there’s an upper bound of 22p. But for 2D cellular automata—like the Game of Life—there is in general no such upper bound, a fact related to the undecidability of the 2D tiling problem. And the result is that there’s no complete, systematic algorithm to find oscillators in a general 2D cellular automaton, or presumably in the Game of Life.

But—as was actually already realized in the mid-1990s—it’s still possible to use algorithmic methods to “fill in” pieces of patterns. The idea is to define part of a pattern of a given period, then use this as a constraint on filling in the rest of it, finding “solutions” that satisfy the constraint using SAT-solving techniques. In practice, this approach has more often been used for spaceships than for oscillators (not least because it’s only practical for small periods). But one feature of it is that it can generate fairly large patterns with a given period.

Yet another method that’s been tried has been to generate oscillators by colliding gliders in many possible ways. But while this is definitely useful if one’s interested in what can be made using gliders, it doesn’t seem to have, for example, allowed people to find much in the way of interesting new oscillators.

Modularity

In traditional engineering a key strategy is modularity. Rather than trying to build something “all in one go”, the idea is to build a collection of independent subsystems, from which the whole system can then be assembled. But how does this work in the Game of Life? We might imagine that to identify the modular parts of a system, we’d have to know the “process” by which the system was put together, and the “intent” involved. But because in the Game of Life we’re ultimately just dealing with pure patterns of bits we can in effect just as well “come in at the end” and algorithmically figure out what pieces are operating as separate, modular parts.

So how can we do this? Basically what we want to find out is which parts of a pattern “operate independently” at a given step, in the sense that these parts don’t have any overlap in the cells they affect. Given that in the rules for the Game of Life a particular cell can affect any of the 9 cells in its ![]() neighborhood, we can say that black cells can only have “overlapping effects” if they are at most

neighborhood, we can say that black cells can only have “overlapping effects” if they are at most ![]() cell units apart. So then we can draw a “nearest neighbor graph” that shows which cells are connected in this sense:

cell units apart. So then we can draw a “nearest neighbor graph” that shows which cells are connected in this sense:

But what about the whole evolution? We can draw what amounts to a causal graph that shows the causal connections between the “independent modular parts” that exist at each step:

And given this, we can summarize the “modular structure” of this particular oscillator by the causal graph:

Ultimately all that matters in the “overall operation” of the oscillator is the partial ordering defined by this graph. Parts that appear “horizontally separated” (or, more precisely, in antichains, or in physics terminology, spacelike separated) can be generated independently and in parallel. But parts that follow each other in the partial order need to be generated in that order (i.e. in physics terms, they are timelike separated).

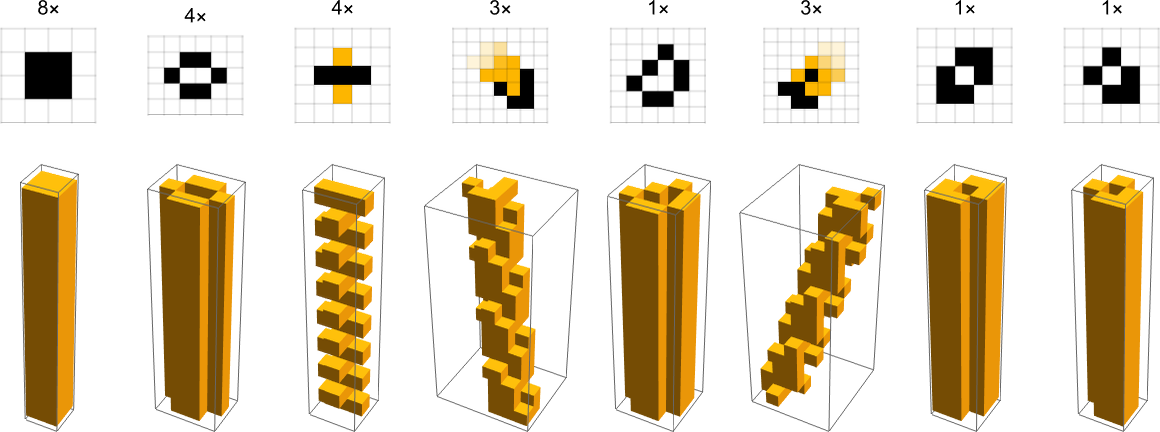

As another example, let’s look at graphs for the various oscillators of period 16 that we showed above:

What we see is that the early period-16 oscillators were quite modular, and had many parts that in effect operated independently. But the later, smaller ones were not so modular. And indeed the last one shown here had no parts that could operate independently; the whole pattern had to be taken together at each step.

And indeed, what we’ll often see is that the more optimized a structure is, the less modular it tends to be. If we’re going to construct something “by hand” we usually need to assemble it in parts, because that’s what allows us to “understand what we’re doing”. But if, for example, we just find a structure in a search, there’s no reason for it to be “understandable”, and there’s no reason for it to be particularly modular.

Different steps in a given oscillator can involve different numbers of modular parts. But as a simple way to assess the “modularity” of an oscillator, we can just ask for the average number of parts over the course of one period. So as an example, here are the results for period-30 oscillators:

Later, we’ll discuss how we can use the level of modularity to assess whether a pattern is likely to have been found by a search or by construction. But for now, this shows how the modularity index has varied over the years for the best known progressively smaller oscillators of a given period—with the main conclusion being that as the oscillators get optimized for size, so also their modularity index tends to decrease:

Gliders & Spaceships

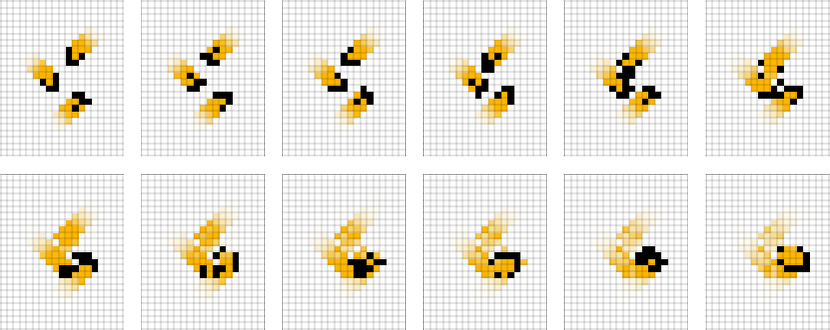

Oscillators are structures that cycle but do not move. “Gliders” and, more generally, “spaceships” are structures that move every time they cycle. When the Game of Life was first introduced, four examples of these (all of period 4) were found almost immediately (the last one being the result of trying to extend the one before it):

Within a couple of years, experimentation had revealed two variants, with periods 12 and 20 respectively, involving additional structures:

But after that, for nearly two decades, no more spaceships were found. In 1989, however, a systematic method for searching was invented, and in the years since, a steady stream of new spaceships have been found. A variety of different periods have been seen

as well as a variety of speeds (and three different angles):

The forms of these spaceships are quite diverse:

Some are “tightly integrated”, while some have many “modular pieces”, as revealed by their causal graphs:

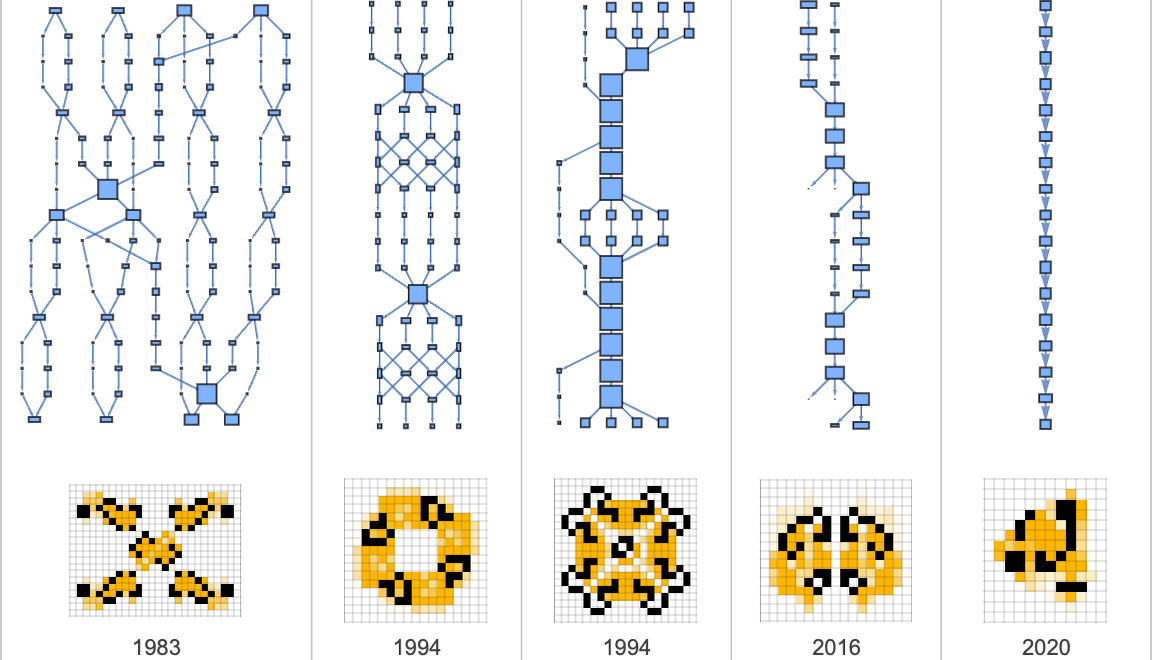

Period-96 spaceships provide an interesting example of the “arc of progress” in the Game of Life. Back in 1971, a systematic enumeration of small polyominoes was done, looking for one that could “reproduce itself”. While no polyomino on its own seemed to do this, a case was found where part of the pattern produced after 48 steps seemed to reappear repeatedly every 48 steps thereafter:

One might expect this repeated behavior to continue forever. But in a typical manifestation of computational irreducibility, it doesn’t, instead stopping its “regeneration” after 24 cycles, and then reaching a steady state (apart from “radiated” gliders) after 3911 steps:

But from an engineering point of view this kind of complexity was just viewed as a nuisance, and efforts were made to “tame” and avoid it.

Adding just one still-life block to the so-called “switch engine”

produces a structure that keeps generating a “periodic wake” forever:

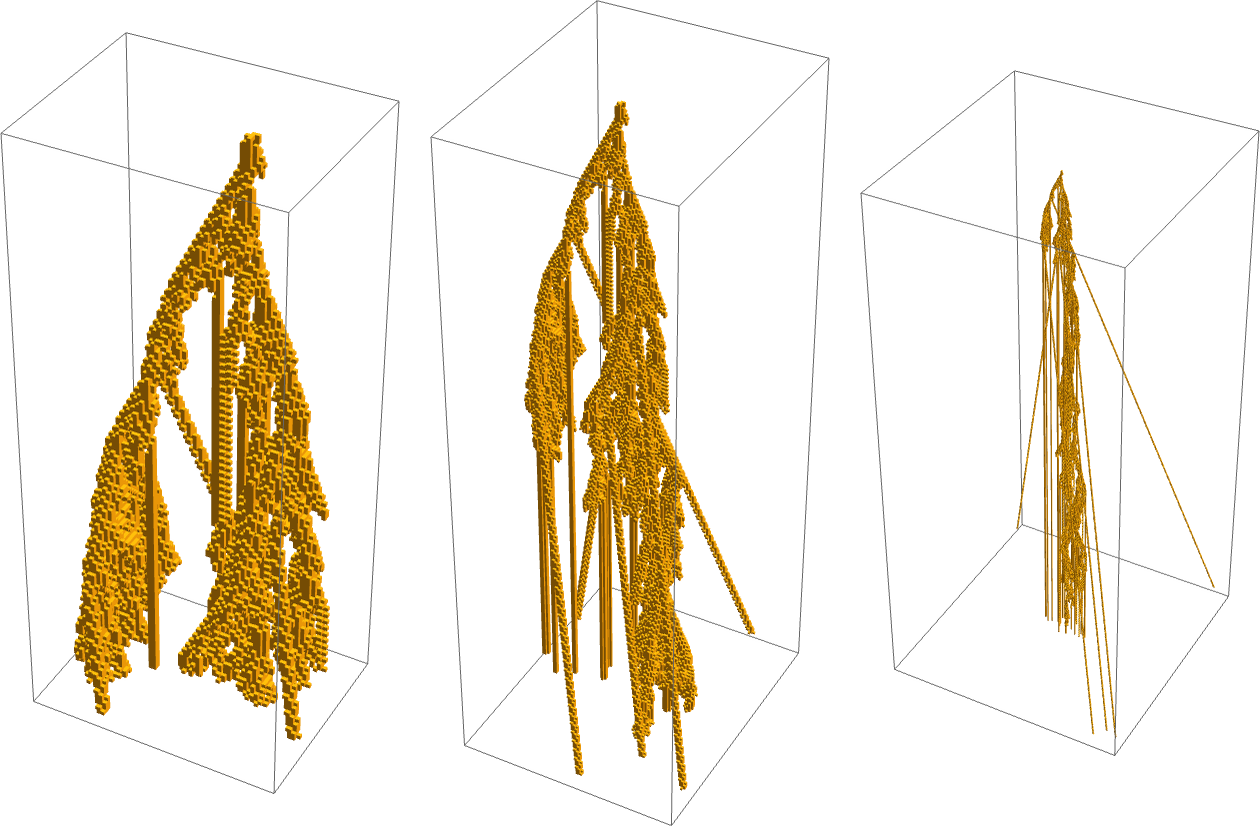

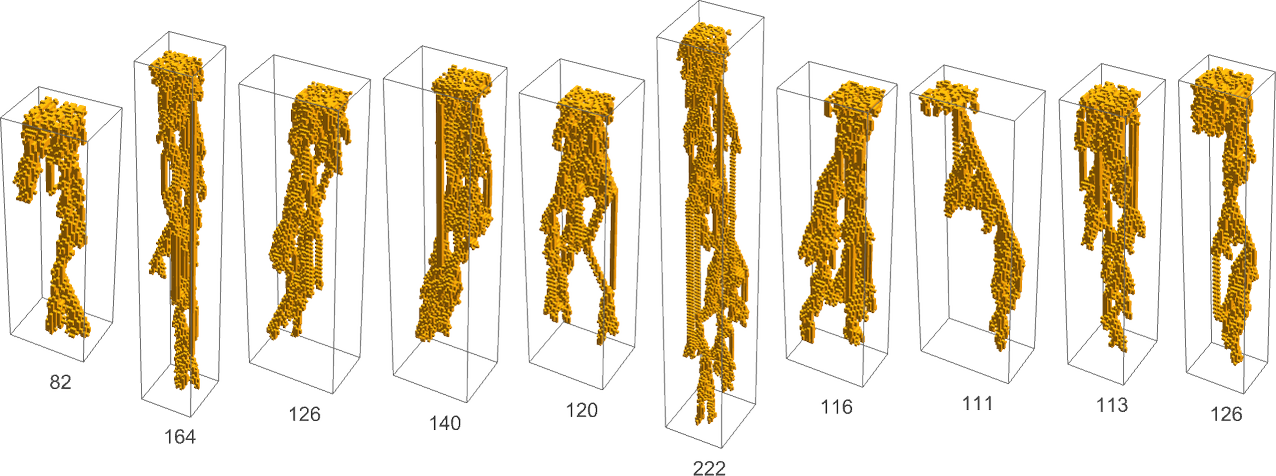

But can this somehow be “refactored” as a “pure spaceship” that doesn’t “leave anything behind”? In 1991 it was discovered that, yes, there was an arrangement of 13 switch engines that could successfully “clean up behind themselves”, to produce a structure that would act as a spaceship with period 96:

But could this be made simpler? It took many years—and tests of many different configurations—but in the end it was found that just 2 switch engines were sufficient:

Looking at the final pattern in spacetime gives a definite impression of “narrowly contained complexity”:

What about the causal graphs? Basically these just decrease in “width” (i.e. number of independent modular parts) as the number of engines decreases:

Like many other things in Game-of-Life engineering, both search and construction have been used to find spaceships. As an extreme example of construction let’s talk about the case of spaceships with speed 31/240. In 2013, an analog of the switch engine above was found—which “eats” blocks 31 cells apart every 240 steps:

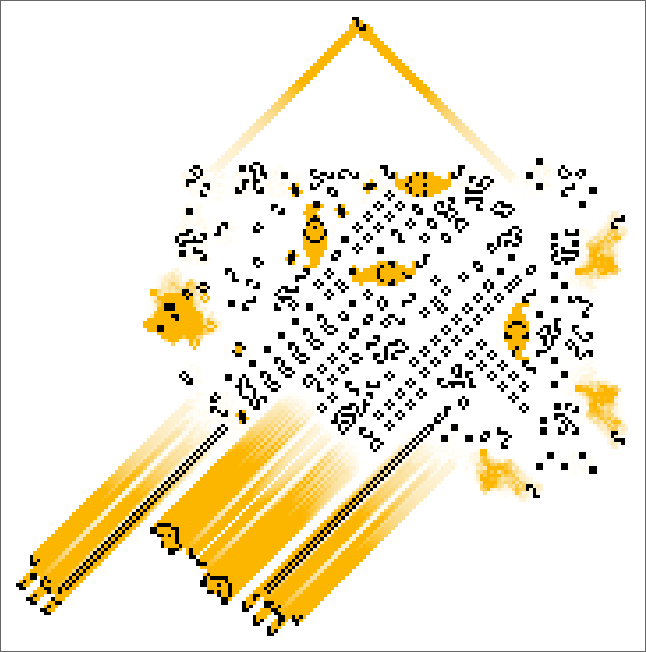

But could this be turned into a “self-sufficient” spaceship? A year later an almost absurdly large (934852×290482) pattern was constructed that did this—by using streams of gliders and spaceships (together with dynamically assembled glider guns) to create appropriate blocks in front, and remove them behind (along with all the “construction equipment” that was used):

By 2016, a pattern with about 700× less area had been constructed. And now, just a few weeks ago, a pattern with 1300× less area (11974×45755) was constructed:

And while this is still huge, it’s still made of modular pieces that operate in an “understandable” way. No doubt there’s a much smaller pattern that operates as a spaceship of the same speed, but—computational irreducibility being what it is—we have no idea how large the pattern might be, or how we might efficiently search for it.

Glider Guns

What can one engineer in the Game of Life? A crucial moment in the development of Game-of-Life engineering was the discovery of the original glider gun in 1970. And what was particularly important about the glider gun is that it was a first example of something that could be thought of as a “signal generator”—that one could imagine would allow one to implement electrical-engineering-style “devices” in the Game of Life.

The original glider gun produces gliders every 30 steps, in a sense defining a “clock speed” of 1/30 for any “circuit” driven by it. Within a year after the original glider gun, two other “slower” glider guns had also been discovered

both working on similar principles, as suggested by their causal graphs:

It wasn’t until 1990 that any additional “guns” were found. And in the years since, a sequence of guns have been found, with a rather wide range of distinct periods:

Some of the guns found have very long periods:

But as part of the effort to do constructions in the 1990s a gun was constructed that had overall period 210, but which interwove multiple glider streams to ultimately produce gliders every 14 steps (which is the maximum rate possible, while avoiding interference of successive gliders):

Over the years, a whole variety of different glider guns have been found. Some are in effect “thoroughly controlled” constructions. Others are more based on some complex process that is reined in to the point where it just produces a stream of gliders and nothing more:

An example of a somewhat surprising glider gun—with the shortest “true period” known—was found in 2024:

The causal graph for this glider gun shows a mixture of irreducible “search-found” parts, together with a collection of “well-known” small modular parts:

By the way, in 2013 it was actually found possible to extend the construction for oscillators of any period to a construction for guns of any period (or at least any period above 78):

In addition to having streams of gliders, it’s also sometimes been found useful to have streams of other “spaceships”. Very early on, it was already known that one could create small spaceships by colliding gliders:

But by the mid-1990s it had been found that direct “spaceship guns” could also be made—and over the years smaller and smaller “optimized” versions have been found:

The last of these—from just last month—has a surprisingly simple structure, being built from components that were already known 30 years ago, and having a causal graph that shows very modular construction:

Building from History

We’ve talked about some of the history of how specific patterns in the Game of Life were found. But what about the overall “flow of engineering progress”? And, in particular, when something new is found, how much does it build on what has been found before? In real-world engineering, things like patent citations potentially give one an indication of this. But in the Game of Life one can approach the question much more systematically and directly, just asking what configurations of bits from older patterns are used in newer ones.

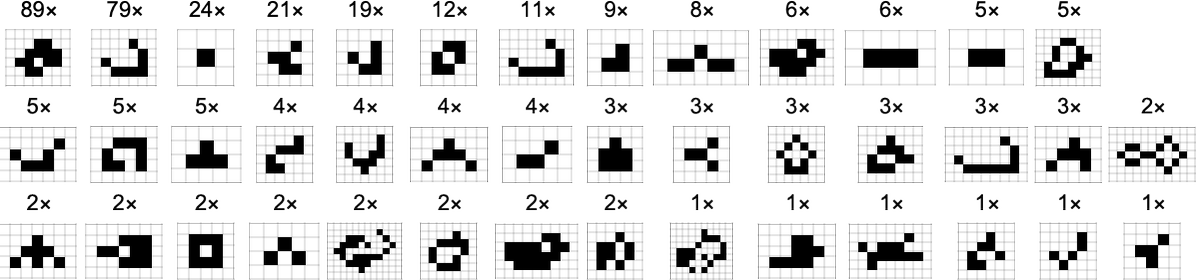

As we discussed above, given a pattern such as

we can pick out its “modular parts”, here rotated to canonical orientations:

Then we can see if these parts correspond to (any phase of) previously known patterns, which in this case they all do:

So now for all structures in the database we can ask what parts they involve. Here’s a plot of the overall frequencies of these parts:

It’s notable that the highest-ranked part is a so-called “eater” that’s often used in constructions, but occurs only quite infrequently in evolution from random initial conditions. It’s also notable that (for no particularly obvious reason) the frequency of the nth most common structure is roughly 1/n.

So when were the various structures that appear here first found? As this picture shows, most—but not all—were found very early in the history of the Game of Life:

In other words, most of the parts used in structures from any time in the history of the Game of Life come from very early in its history. Or, in effect, structures typically go “back to basics” in the parts they use.

Here’s a more detailed picture, showing the relative amount of use of each part in structures from each year:

There are definite “fashions” to be seen here, with some structures “coming into fashion” for a while (sometimes, but not always, right after they were first found), and then dropping out.

One might perhaps imagine that smaller parts (i.e. ones with smaller areas) would be more popular than larger ones. But plotting areas of parts against their rank, we see that there are some large parts that are quite common, and some small ones that are rare:

We’ve seen that many of the most popular parts overall are ones that were found early in the history of the Game of Life. But plenty of distinct modular parts were also found much later. This shows the number of distinct new modular parts found across all patterns in successive years:

Normalizing by the number of new patterns found each year, we see a general gradual increase in the relative number of new modular parts, presumably reflecting the greater use of search in finding patterns, or components of patterns:

But how important have these later-found modular parts been? This shows the total rate at which modular parts found in a given year were subsequently used—and what we see, once again, is that parts found early are overwhelmingly the ones that are subsequently used:

A somewhat complementary way to look at this is to ask of all patterns found in a given year, how many are “purely de novo”, in the sense that they use no previously found modular parts (as indicated in red), and how many use previously found parts:

A cumulative version of this makes it clear that in early years most patterns are purely de novo, but later on, there’s an increasing amount of “reuse” of previously found parts—or, in other words, in later years the “engineering history” is increasingly important:

It should be said, however, that if one wants the full story of “what’s being used” it’s a bit more nuanced. Because here we’re always treating each modular part of each pattern as a separate entity, so that we consider any given pattern to “depend” only on base modular parts. But “really” it could depend on another whole structure, itself built of many modular parts. And in what we’re doing here, we’re not tracking that hierarchy of dependencies. Were we to do so, we would likely be able to see more complex “technology stacks” in the Game of Life. But instead we’re always “going down to the primitives”. (If we were dealing with electronics it’d be like asking “What are the transistors and capacitors that are being used?”, rather than “What is the caching architecture, or how is the floating point unit set up?”)

OK, but in terms of “base modular parts” a simple question to ask is how many get used in each pattern. This shows the number of (base) modular parts in patterns found in each year:

There are always a certain number of patterns that just consist of a single modular part—and, as we saw above, that was more common earlier in the history of the Game of Life. But now we also see that there have been an increasing number of patterns that use many modular parts—typically reflecting a higher degree of “construction” (rather than search) going on.

By the way, for comparison, these plots show the total areas and the numbers of (black) cells in patterns found in each year; both show increases early on, but more or less level off by the 1990s:

But, OK, if we look across all patterns in the database, how many parts do they end up using? Here’s the overall distribution:

At least for a certain range of numbers of parts, this falls roughly exponentially, reflecting the idea that it’s been exponentially less likely for people to come up with (or find) patterns that have progressively larger numbers of distinct modular parts.

How has this changed over time? This shows a cumulative plot of the relative frequencies with which different numbers of modular parts appear in patterns up to a given year

indicating that over time the distribution of the number of modular parts has gotten progressively broader—or, in other words, as we’ve seen in other ways above, more patterns make use of larger numbers of modular parts.

We’ve been looking at all the patterns that have been found. But we can also ask, say, just about oscillators. And then we can ask, for example, which oscillators (with which periods) contain which others, as in:

And looking at all known oscillators we can see how common different “oscillator primitives” are in building up other oscillators:

We can also ask in which year “oscillator primitives” at different ranks were found. Unlike in the case of all structures above, we now see that some oscillator primitives that were found only quite recently appear at fairly high ranks—reflecting the fact that in this case, once a primitive has been found, it’s often immediately useful in making oscillators that have multiples of its period:

Lifetime Hacking and Die Hards

We can think of almost everything we’ve talked about so far as being aimed at creating structures (like “clocks” and “wires”) that are recognizably useful for building traditional “machine-like” engineering systems. But a different possible objective is to find patterns that have some feature we can recognize, whether with obvious immediate “utility” or not. And as one example of this we can think about finding so-called “die hard” patterns that live as long as possible before dying out.

The phenomenon of computational irreducibility tells us that even given a particular pattern we can’t in general “know in advance” how long it’s going to take to die out (or if it ultimately dies out at all). So it’s inevitable that the problem of finding ultimate die-hard patterns can be unboundedly difficult, just like analogous problems for other computational systems (such as finding so-called “busy beavers” in Turing machines).

But in practice one can use both search and construction techniques to find patterns that at least live a long time (even if not the very longest possible time). And as an example, here’s a very simple pattern (found by search) that lives for 132 steps before dying out (the “puff” at the end on the left is a reflection of how we’re showing “trails”; all the actual cells are zero at that point):

Searching nearly 1016 randomly chosen 16×16 patterns (out of a total of ≈ 1077 possible such patterns), the longest lifetime found is 1413 steps—achieved with a rather random-looking initial pattern:

But is this the best one can do? Well, no. Just consider a block and a spaceship n cells apart. It’ll take 2n steps for them to collide, and if the phases are right, annihilate each other:

So by picking the separation n to be large enough, we can make this configuration “live as long as we want”. But what if we limit the size of the initial pattern, say to 32×32? In 2022 the following pattern was constructed:

And this pattern is carefully set up so that after 30,274 steps, everything lines up and it dies out, as we can see in the (vertically foreshortened) spacetime diagram on the left:

And, yes, the construction here clearly goes much further than search was able to reach. But can we go yet further? In 2023 a 116×86 pattern was constructed

that it was proved eventually dies out, but only after the absurdly large number of 17↑↑↑3 steps (probably even much larger than the number of emes in the ruliad), as given by:

or

The Comparison with Adaptive Evolution

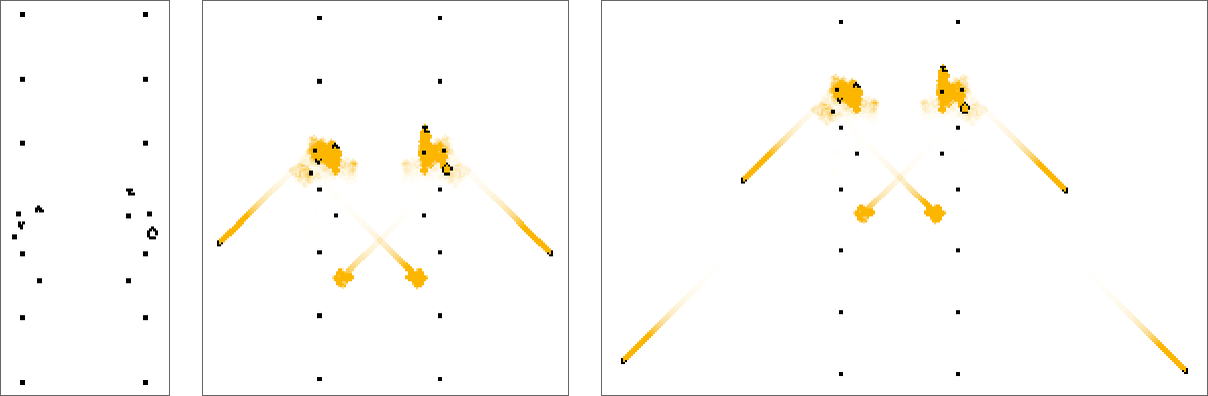

There are some definite rough ways in which technology development parallels biological evolution. Both involve the concept of trying out possibilities and building on ones that work. But technology development has always ultimately been driven by human effort, whereas biological evolution is, in effect, a “blind” process, based on the natural selection of random mutations. So what happens if we try to apply something like biological evolution to the Game of Life? As an example, let’s look at adaptive evolution that’s trying to maximize finite lifetime based on making a sequence of random point mutations within an initially random 16×16 pattern. Most of those mutations don’t give patterns with larger (finite) lifetimes, but occasionally there’s a “breakthrough” and the lifetime achieved so far jumps up:

The actual behaviors corresponding to the breakthroughs in this case are:

And here are some other outcomes from adaptive evolution:

In almost all cases, a limited number of steps of adaptive evolution do succeed in generating patterns with fairly long finite lifetimes. But the behavior we see typically shows no “readily understandable mechanisms”—and no obviously separable modular parts. And instead—just like in my recent studies of both biological evolution and machine learning—what we get are basically “lumps of irreducible computation” that “just happen” to show what we’re looking for (here, long lifetime).

Invented or Discovered? Made for a Purpose at All?

Let’s say we’re presented with an array of cells that’s an initial condition for the Game of Life. Can we tell “where it came from”? Is it “just arbitrary” (or “random”)? Or was it “set up for a purpose”? And if it was “set up for a purpose”, was it “invented” (and “constructed”) for that purpose, or was it just “discovered” (say by a search) to fulfill that purpose?

Whether one’s dealing with archaeology, evolutionary biology, forensic science, the identification of alien intelligence or, for that matter, theology, the question of whether something “was set up for a purpose” is a philosophically fraught one. Any behavior one sees one can potentially explain either in terms of the mechanism that produces it, or in terms of what it “achieves”. Things get a little clearer if we have a particular language for describing both mechanisms and purposes. Then we can ask questions like: “Is the behavior we care about more succinctly described in terms of its mechanism or its purpose?” So, for example, “It behaves as a period-15 glider gun” might be an adequate purpose-oriented description, that’s much shorter than a mechanism-oriented description in terms of arrangements of cells.

But what is the appropriate “lexicon of purposes” for the Game of Life? In effect, that’s a core question for Game-of-Life engineering. Because what engineering—and technology in general—is ultimately about is taking whatever raw material is available (whether from the physical world, or from the Game of Life) and somehow fashioning it into something that aligns with human purposes. But then we’re back to what counts as a valid human purpose. How deeply does the purpose have to connect in to everything we do? Is it, for example, enough for something to “look nice”, or is that not “utilitarian enough”? There aren’t absolute answers to these questions. And indeed the answers can change over time, as new uses for things are discovered (or invented).

But for the Game of Life we can start with some of the “purposes” we’ve discussed here—like “be an oscillator of a certain period”, “reflect gliders”, “generate the primes” or even just “die after as long as possible”. Let’s say we just start enumerating possible initial patterns, either randomly, or exhaustively. How often will we come across patterns that “achieve one of these purposes”? And will it “only achieve that purpose” or will it also “do extra stuff” that “seems irrelevant”?

As an example, consider enumerating all possible 3×3 patterns of cells. There are altogether

Other patterns can take a while to “become period 2”, but then at least give “pure period-2 objects”. And for example this one can be interpreted as being the smallest precursor, and taking the least time, to reach the period-2 object it produces:

There are other cases that “get to the same place” but seem to “wander around” doing so, and therefore don’t seem as convincing as having been “created for the purpose of making a period-2 oscillator”:

Then there are much more egregious cases. Like

which after 173 steps gives

but only after going through all sorts of complicated intermediate behavior

that definitely doesn’t make it look like it’s going “straight to its purpose” (unless perhaps its purpose is to produce that final pattern from the smallest initial precursor, etc.).

But, OK. Let’s imagine we have a pattern that “goes straight to” some “recognizable purpose” (like being an oscillator of a certain period). The next question is: was that pattern explicitly constructed with an understanding of how it would achieve its purpose, or was it instead “blindly found” by some kind of search?

As an example, let’s look at some period-9 oscillators:

One like

seems like it must have been constructed out of “existing parts”, while one like

seems like it could only plausibly have been found by a search.

Spacetime views don’t tell us much in these particular cases:

But causal graphs are much more revealing:

They show that in the first case there are lots of “factored modular parts”, while in the second case there’s basically just one “irreducible blob” with no obvious separable parts. And we can view this as an immediate signal for “how human” each pattern is. In a sense it’s a reflection of the computational boundedness of our minds. When there are factored modular parts that interact fairly rarely and each behave in a fairly simple way, it’s realistic for us to “get our minds around” what’s going on. But when there’s just an “irreducible blob of activity” we’d have to compute too much and keep too much in mind at once for us to be able to really “understand what’s going on” and for example produce a human-level narrative explanation of it.

If we find a pattern by search, however, we don’t really have to “understand it”; it’s just something we computationally “discover out there in the computational universe” that “happens” to do what we want. And, indeed, as in the example here, it often does what it does in a quite minimal (if incomprehensible) way. Something that’s found by human effort is much less likely to be minimal; in effect it’s at least somewhat “optimized for comprehensibility” rather than for minimality or ease of being found by search. And indeed it will often be far too big (e.g. in terms of number of cells) for any pure exhaustive or random search to plausibly find it—even though the “human-level narrative” for it might be quite short.

Here are the causal graphs for all the period-9 oscillators from above:

Some we can see can readily be broken down into multiple rarely interacting distinct components; others can’t be decomposed in this kind of way. And in a first approximation, the “decomposable” ones seem to be precisely those that were somehow “constructed by human effort”, while the non-decomposable ones seem to be those that were “discovered by searches”.

Typically, the way the “constructions” are done is to start with some collection of known parts, then, by trial and error (sometimes computer assisted) see how these can be fit together to get something that does what one wants. Searches, on the other hand, typically operate on “raw” configurations of cells, blindly going through a large number of possible configurations, at every stage automatically testing whether one’s got something that does what one wants.

And in the end these different strategies reveal themselves in the character of the final patterns they produce, and in the causal graphs that represent these patterns and their behavior.

Principles of Engineering Strategy from the Game of Life

In engineering as it’s traditionally been practiced, the main emphasis tends to be on figuring out plans, and then constructing things based on those plans. Typically one starts from components one has, then tries to figure out how to combine them to incrementally build up what one wants.

And, as we’ve discussed, this is also a way of developing technology in the Game of Life. But as we’ve discussed at length, it’s not the only way. Another way is just to search for whole pieces of technology one wants.

Traditional intuition might make one assume this would be hopeless. But the repeated lesson of my discoveries about simple programs—as well as what’s been done with the Game of Life—is that actually it’s often not hopeless at all, and instead it’s very powerful.

Yes, what you get is not likely to be readily “understandable”. But it is likely to be minimal and potentially quite optimal for whatever it is that it does. I’ve often talked of this approach as “mining from the computational universe”. And over the course of many years I’ve had success with it in all sorts of disparate areas. And now, here, we’ve see in the Game of Life a particularly clean example where search is used alongside construction in developing technology.

It’s a feature of things produced by construction that they are “born understandable”. In effect, they are computationally reducible enough that we can “fit them in our finite minds” and “understand them”. But things found by search don’t have this feature. And most of the time the behavior they’ll show will be full of computational irreducibility.

In both biological evolution and machine learning my recent investigations suggest that most of what we’re seeing are “lumps of irreducible computation” found at random that just “happen to achieve the necessary objectives”. This hasn’t been something familiar in traditional engineering, but it’s something tremendously powerful. And from the examples we’ve seen here in the Game of Life it’s clear that it can often achieve things that seem completely inaccessible by traditional methods based on explicit construction.

At first we might assume that irreducible computation is too unruly and unpredictable to be useful in achieving “understandable objectives”. But if we find just the right piece of irreducible computation then it’ll achieve the objective we want, often in a very minimal way. And the point is that the computational universe is in a sense big enough that we’ll usually be able to find that “right piece of irreducible computation”.

One thing we see in Game-of-Life engineering is something that’s in a sense a compromise between irreducible computation and predictable construction. The basic idea is to take something that’s computationally irreducible, and to “put it in a cage” that constrains it to do what one wants. The computational irreducibility is in a sense the “spark” in the system; the cage provides the control we need to harness that spark in a way that meets our objectives.

Let’s look at some examples. As our “spark” we’ll use the R pentomino ![]() that we discussed at the very beginning. On its own, this generates all sorts of complex behavior—that for the most part doesn’t align with typical objectives we might define (though as a “side show” it does happen to generate gliders). But the idea is to put constraints on the R pentomino to make it “useful”.

that we discussed at the very beginning. On its own, this generates all sorts of complex behavior—that for the most part doesn’t align with typical objectives we might define (though as a “side show” it does happen to generate gliders). But the idea is to put constraints on the R pentomino to make it “useful”.

Here’s a case where we’ve tried to “build a road” for the R pentomino to go down:

And looking at this every 18 steps we see that, at least for a while, the R pentomino has indeed moved down the road. But it’s also generated something of an “explosion”, and eventually this explosion catches up, and the R pentomino is destroyed.

So can we maintain enough control to let the R pentomino survive? The answer is yes. And here, for example, is a period-12 oscillator, “powered” by an R pentomino at its center:

Without the R pentomino, the structure we’ve set up cycles with period 6:

And when we insert the R pentomino this structure “keeps it under control”—so that the only effect it ultimately has is to double the period, t0 12.

Here’s a more dramatic example. Start with a static configuration of four so-called “eaters”:

Now insert two R pentominoes. They’ll start doing their thing, generating what seems like quite random behavior. But the “cage” defined by the “eaters” limits what can happen, and in the end what emerges is an oscillator—that has period 129:

What else can one “make R pentominoes do”? Well, with appropriate harnesses, they can for example be used to “power” oscillators with many different periods:

“Be an oscillator of a certain period” is in a sense a simple objective. But what about more complex objectives? Of course, any pattern of cells in the Game of Life will do something. But the question is whether that something aligns with technological objectives we have.

Generically, things in the Game of Life will behave in computationally irreducible ways. And it’s this very fact that gives such richness to what can be done with the Game of Life. But can the computational irreducibility be controlled—and harnessed for technological purposes? In a sense that is the core challenge of engineering in both the Game of Life, and in the real world. (It’s also rather directly the challenge we face in making use of the computational power of AI, but still adequately aligning it with human objectives.)

As we look at the arc of technological development in the Game of Life we see over the course of half a century all sorts of different advances being made. But will there be an end to this? Will we eventually run out of inventions and discoveries? The underlying presence of computational irreducibility makes it clear that we will not. The only thing that might end is the set of objectives we’re trying to meet. We now know how to make oscillators of any period. And unless we insist on for example finding the smallest oscillator of a given period, we can consider the problem of finding oscillators solved, with nothing more to discover.

In the real world nature and the evolution of the universe inevitably confront us with new issues, which lead to new objectives. In the Game of Life—as in any other abstract area, like mathematics—the issue of defining new objectives is up to us. Computational irreducibility leads to infinite diversity and richness of what’s possible. The issue for us is to figure out what direction we want to go. And the story of engineering and technology in the Game of Life gives us, in effect, a simple model for the issues we confront in other areas of technology, like AI.

Some Personal Backstory

I’m not sure if I made the right decision back in 1981. I had come up with a very simple class of systems and was doing computer experiments on them, and was starting to get some interesting results. And when I mentioned what I was doing to a group of (then young) computer scientists they said “Oh, those things you’re studying are called cellular automata”. Well, actually, the cellular automata they were talking about were 2D systems while mine were 1D. And though that might seem like a technical difference, it has a big effect on one’s impression of what’s going on—because in 1D one can readily see “spacetime histories” that gave an immediate sense of the “whole behavior of the system”, while in 2D one basically can’t.

I wondered what to call my models. I toyed with the term “polymones”—as a modernized nod to Leibniz’s monads. But in the end I decided that I should stick with a simpler connection to history, and just call my models, like their 2D analogs, “cellular automata”. In many ways I’m happy with that decision. Though one of its downsides has been a certain amount of conceptual confusion—more than anything centered around the Game of Life.

People often know that the Game of Life is an example of a cellular automaton. And they also know that within the Game of Life lots of structures (like gliders and glider guns) can be set up to do particular things. Meanwhile, they hear about my discoveries about the generation of complexity in cellular automata (like rule 30). And somehow they conflate these things—leading to all too many books etc. that show pictures of simple gliders in the Game of Life and say “Look at all this complexity!”

At some level it’s a confusion between science and engineering. My efforts around cellular automata have centered on empirical science questions like “What does this cellular automaton do if you run it?” But—as I’ve discussed at length above—most of what’s been done with the Game of Life has centered instead on questions of engineering, like “What recognizable (or useful) structures can you build in the system?” It’s a different objective, with different results. And, in particular, by asking to “engineer understandable technology” one’s specifically eschewing the phenomenon of computational irreducibility—and the whole story of the emergence of complexity that’s been so central to my own scientific work on cellular automata and so much else.

Many times over the years, people would show me things they’d been able to build in the Game of Life—and I really wouldn’t know what to make of them. Yes, they seemed like impressive hacks. But what was the big picture? Was this just fun, or was there some broader intellectual point? Well, finally, not long ago I realized: this is not a story of science, it’s a story about the arc of engineering, or what one can call “metaengineering”.

And back in 2018, in connection with the upcoming 50th anniversary of the Game of Life, I decided to see what I could figure out about this. But I wasn’t satisfied with how far I got, and other priorities interceded. So—beyond one small comment that ended up in a 2020 New York Times article—I didn’t write anything about what I’d done. And the project languished. Until now. When somehow my long-time interest in “alien engineering”, combined with my recent results about biological evolution coalesced into a feeling that it was time to finally figure out what we could learn from all that effort that’s been put into the Game of Life.

In a sense this brings closure to a very long-running story for me. The first time I heard about the Game of Life was in 1973. I was an early teenager then, and I’d just gotten access to a computer. By today’s standards the computer (an Elliott 903C) was a primitive one: the size of a desk, programmed with paper tape, with only 24 kilobytes of memory. I was interested in using it for things like writing a simulator for the physics of idealized gas molecules. But other kids who had access to the computer were instead more interested (much as many kids might be today) in writing games. Someone wrote a “Hunt the Wumpus” game. And someone else wrote a program for the “Game of Life”. The configurations of cells at each generation were printed out on a teleprinter. And for some reason people were particularly taken with the “Cheshire cat” configuration, in which all that was left at the end (as in Alice in Wonderland) was a “smile”. At the time, I absolutely didn’t see the point of any of this. I was interested in science, not games, and the Game of Life pretty much lost me at “Game”.

For a number of years I didn’t have any further contact with the Game of Life. But then I met Bill Gosper, who I later learned had in 1970 discovered the glider gun in the Game of Life. I met Gosper first “online” (yes, even in 1978 that was a thing, at least if you used the MIT-MC computer through the ARPANET)—then in person in 1979. And in 1980 I visited him at Xerox PARC, where he described himself as part of the “entertainment division” and gave me strange math formulas printed on a not-yet-out-of-the-lab color laser printer

and also showed me a bitmapped display (complete with GUI) with lots of pixels dancing around that he enthusiastically explained were showing the Game of Life. Knowing what I know now, I would have been excited by what I saw. But at the time, it didn’t really register.

Still, in 1981, having started my big investigation of 1D cellular automata, and having made the connection to the 2D case of the Game of Life, I started wondering whether there was something “scientifically useful” that I could glean from all the effort I knew (particularly from Gosper) had been put into Life. It didn’t help that almost none of the output of that effort had been published. And in those days before the web, personal contact was pretty much the only way to get unpublished material. One of my larger “finds” was from a friend of mine from Oxford who passed on “lab notebook pages” he’d got from someone who was enumerating outcomes from different Game-of-Life initial configurations:

And from material like this, as well as my own simulations, I came up with some tentative “scientific conclusions”, which I summarized in 1982 in a paragraph in my first big paper about cellular automata:

But then, at the beginning of 1983, as part of my continuing effort to do science on cellular automata, I made a discovery. Among all cellular automata there seemed to be four basic classes of behavior, with class 4 being characterized by the presence of localized structures, sometimes just periodic, and sometimes moving:

I immediately recognized the analogy to the Game of Life, and to oscillators and gliders there. And indeed this analogy was part of what “tipped me off” to thinking about the ubiquitous computational capabilities of cellular automata, and to the phenomenon of computational irreducibility.

Meanwhile, in March 1983, I co-organized what was effectively the first-ever conference on cellular automata (held at Los Alamos)—and one of the people I invited was Gosper. He announced his Hashlife algorithm (which was crucial to future Life research) there, and came bearing gifts: printouts for me of Life, that I annotated, and still have in my archives:

I asked Gosper to do some “more scientific” experiments for me—for example starting from a region of randomness, then seeing what happened:

But Gosper really wasn’t interested in what I saw as being science; he wanted to do engineering, and make constructions—like this one he gave me, showing two glider guns exchanging streams of gliders (why would one care, I wondered):

I’d mostly studied 1D cellular automata—where I’d discovered a lot by systematically looking at their behavior “laid out in spacetime”. But in early 1984 I resolved to also systematically check out 2D cellular automata. And mostly the resounding conclusion was that their basic behavior was very similar to 1D. Out of all the rules we studied, the Game of Life didn’t particularly stand out. But—mostly to provide a familiar comparison point—I included pictures of it in the paper we wrote:

And we also went to the trouble of making a 3D “spacetime” picture of the Game of Life on a Cray supercomputer—though it was too small to show anything terribly interesting:

It had been a column in Scientific American in 1970 that had first propelled the Game of Life to public prominence—and that had also launched the first great Life engineering challenge of finding a glider gun. And in both 1984 and 1985 a successor to that very same column ran stories about my 1D cellular automata. And in 1985, in collaboration with Scientific American, I thought it would be fun and interesting to reprise the 1970 glider gun challenge, but now for 1D class 4 cellular automata:

Many people participated. And my main conclusion was: yes, it seemed like one could do the same kinds of engineering in typical 1D class 4 cellular automata as one could in the Game of Life. But this was all several years before the web, and the kind of online community that has driven so much Game of Life engineering in modern times wasn’t yet able to form.

Meanwhile, by the next year, I was starting the development of Mathematica and what’s now the Wolfram Language, and for a few years didn’t have much time to think about cellular automata. But in 1987 when Gosper got involved in making pre-release demos of Mathematica he once again excitedly told me about his discoveries in the Game of Life, and gave me pictures like:

It was in 1992 that the Game of Life once again appeared in my life. I had recently embarked on what would become the 10-year project of writing my book A New Kind of Science. I was working on one of the rather few “I already have this figured out” sections in the book—and I wanted to compare class 4 behavior in 1D and 2D. How was I to display the Game of Life, especially in a static book? Equipped with what’s now the Wolfram Language it was easy to come up with visualizations—looking “out” into a spacetime slice with more distant cells “in a fog”, as well as “down” into a fog of successive states: