Empirical Theoretical Computer Science

“Could there be a faster program for that?” It’s a fundamental type of question in theoretical computer science. But except in special cases, such a question has proved fiendishly difficult to answer. And, for example, in half a century, almost no progress has been made even on the rather coarse (though very famous) P vs. NP question—essentially of whether for any nondeterministic program there will always be a deterministic one that is as fast. From a purely theoretical point of view, it’s never been very clear how to even start addressing such a question. But what if one were to look at the question empirically, say in effect just by enumerating possible programs and explicitly seeing how fast they are, etc.?

One might imagine that any programs one could realistically enumerate would be too small to be interesting. But what I discovered in the early 1980s is that this is absolutely not the case—and that in fact it’s very common for programs even small enough to be easily enumerated to show extremely rich and complex behavior. With this intuition I already in the 1990s began some empirical exploration of things like the fastest ways to compute functions with Turing machines. But now—particularly with the concept of the ruliad—we have a framework for thinking more systematically about the space of possible programs, and so I’ve decided to look again at what can be discovered by ruliological investigations of the computational universe about questions of computational complexity theory that have arisen in theoretical computer science—including the P vs. NP question.

We won’t resolve the P vs. NP question. But we will get a host of definite, more restricted results. And by looking “underneath the general theory” at explicit, concrete cases we’ll get a sense of some of the fundamental issues and subtleties of the P vs. NP question, and why, for example, proofs about it are likely to be so difficult.

Along the way, we’ll also see lots of evidence of the phenomenon of computational irreducibility—and the general pattern of the difficulty of computation. We’ll see that there are computations that can be “reduced”, and done more quickly. But there are also others where we’ll be able to see with absolute explicitness that—at least within the class of programs we’re studying—there’s simply no faster way to get the computations done. In effect this is going to give us lots of proofs of restricted forms of computational irreducibility. And seeing these will give us ways to further build our intuition about the ever-more-central phenomenon of computational irreducibility—as well as to see how in general we can use the methodology of ruliology to explore questions of theoretical computer science.

The Basic Setup

Click any diagram to get Wolfram Language code to reproduce it.

How can we enumerate possible programs? We could pick any model of computation. But to help connect with traditional theoretical computer science, I’ll use a classic one: Turing machines.

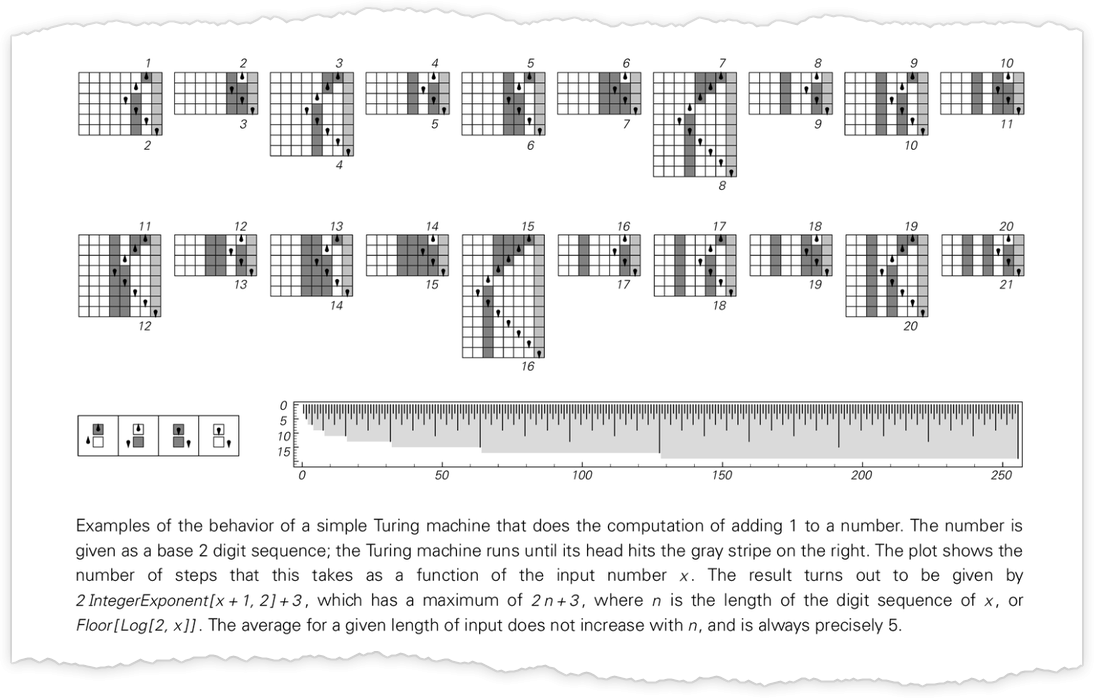

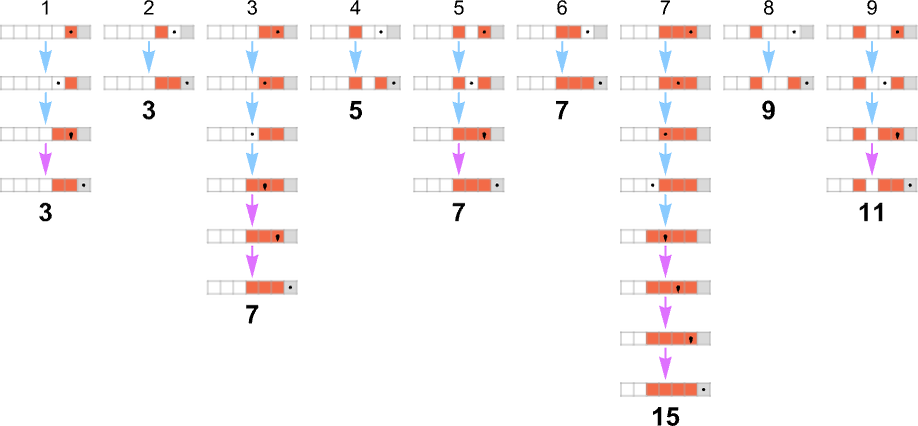

Often in theoretical computer science one concentrates on yes/no decision problems. But here it’ll typically be convenient instead to think (more “mathematically”) about Turing machines that compute integer functions. The setup we’ll use is as follows. Start the Turing machine with the digits of some integer n on its tape. Then run the Turing machine, stopping if the Turing machine head goes further to the right than where it started. The value of the function with input n is then read off from the binary digits that remain on its tape when the Turing machine stops. (There are many other “halting” criteria we could use, but this is a particularly robust and convenient one.)

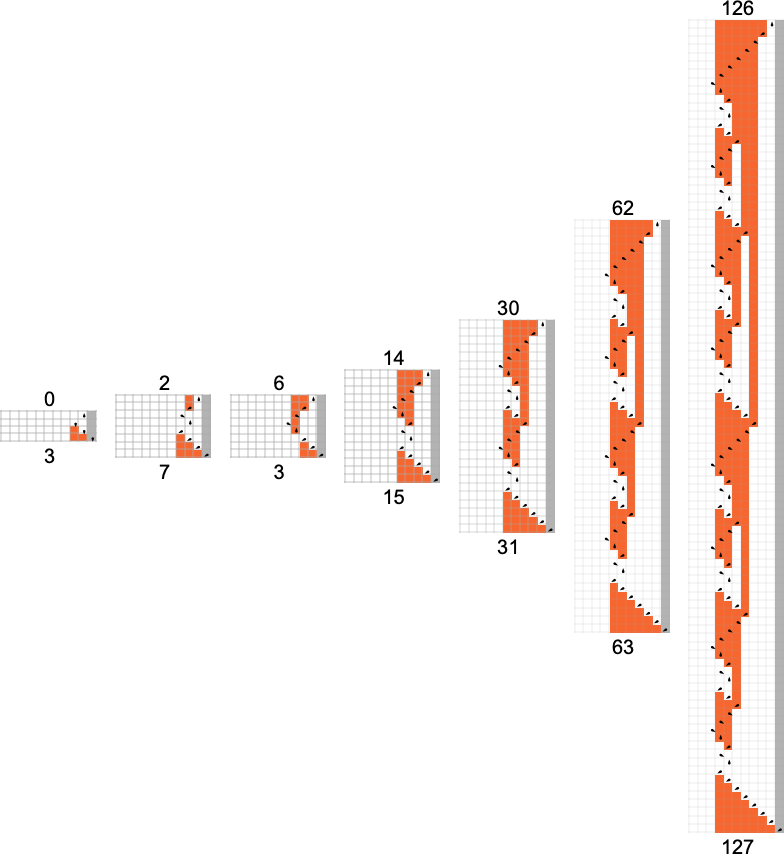

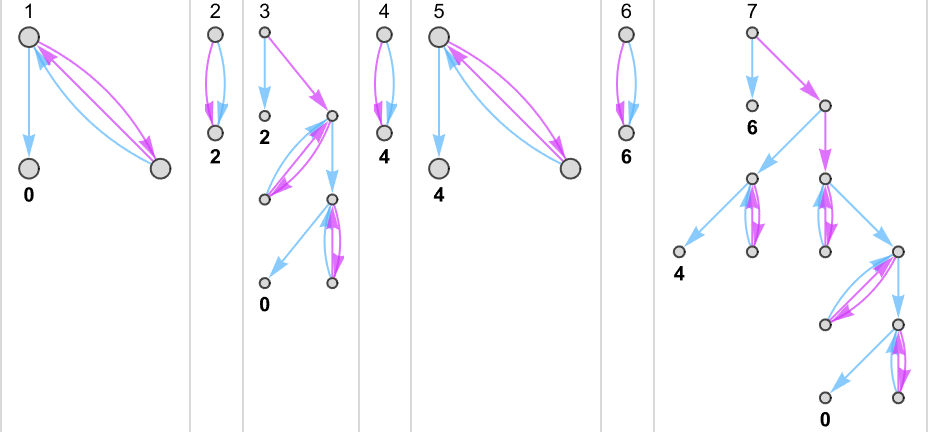

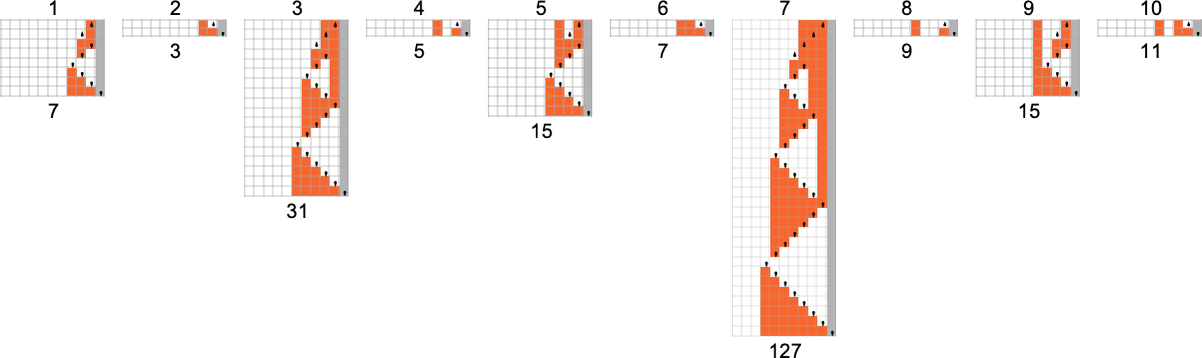

So for example, given a Turing machine with rule

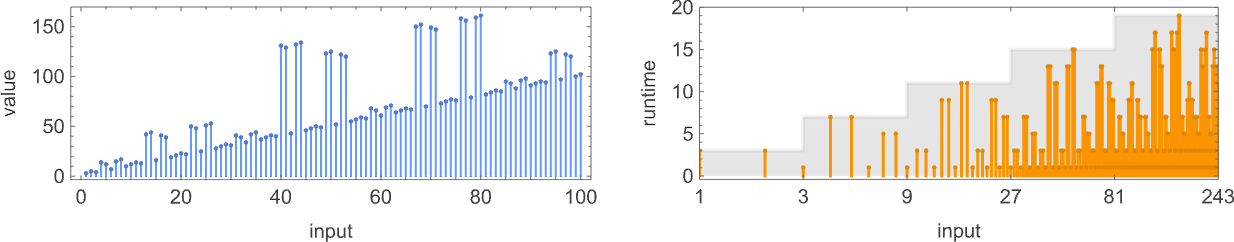

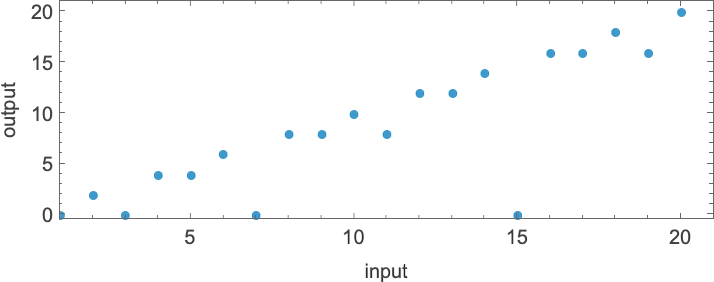

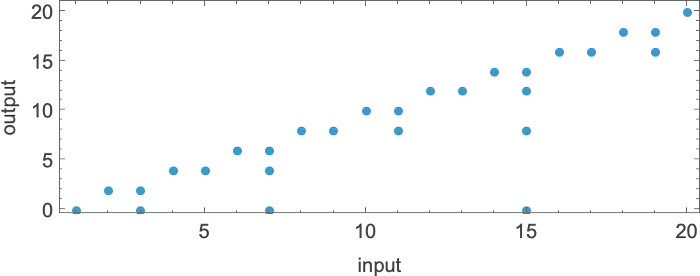

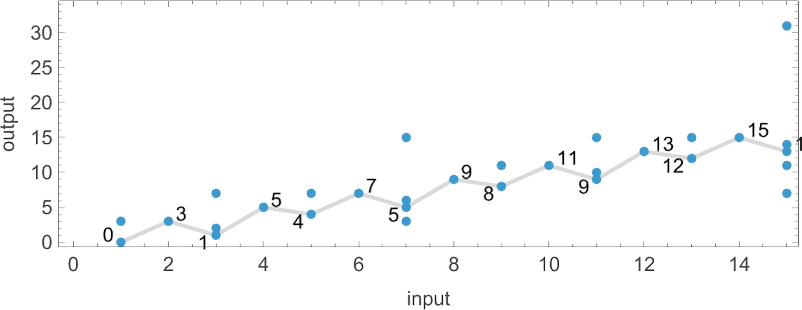

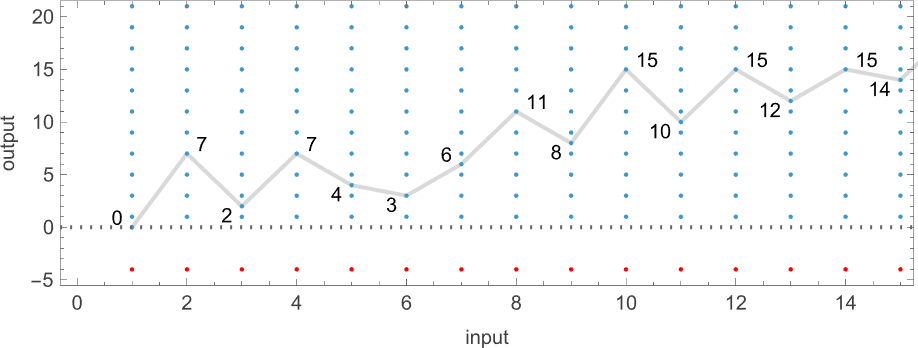

we can feed it successive integers as input, then run the machine to find the successive values it computes:

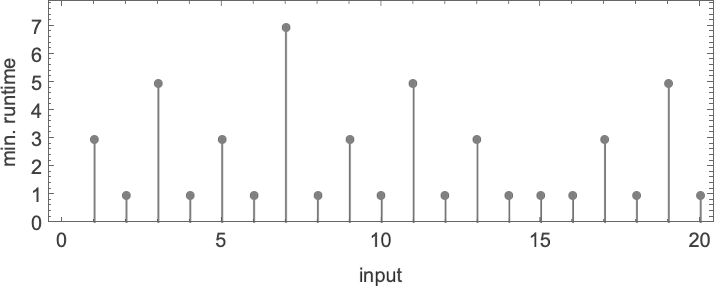

In this case, the function that the Turing machine computes is

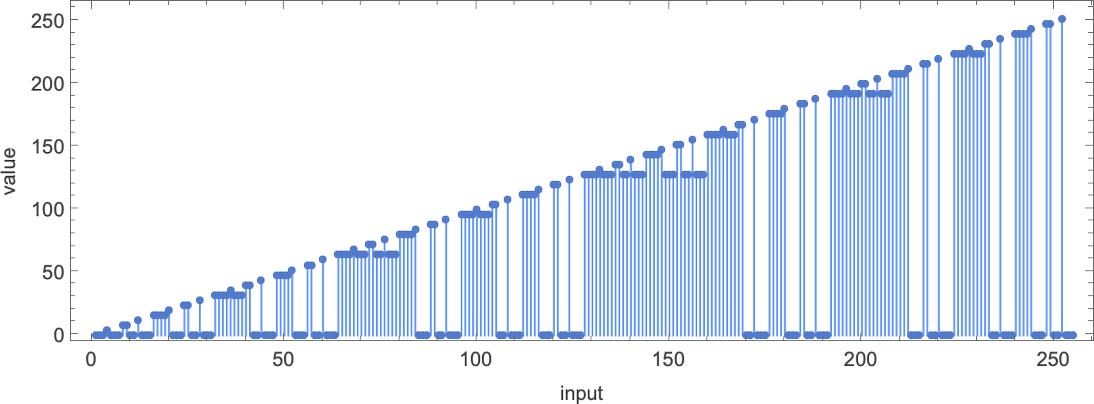

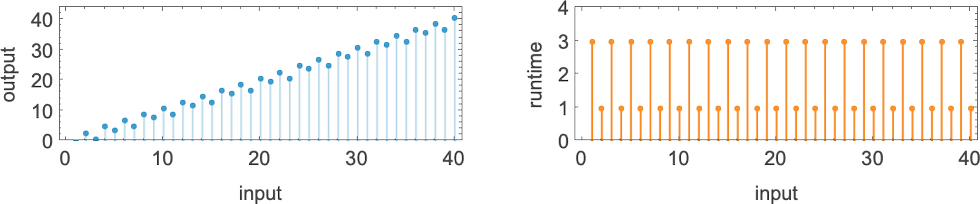

or in graphical form:

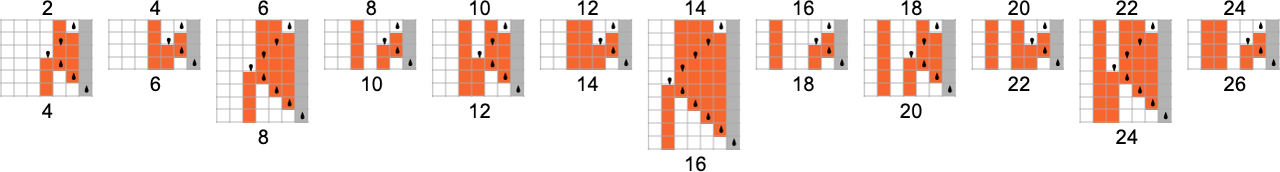

For each input, the Turing machine takes a certain number of steps to stop and give its output (i.e. the value of the function):

But this particular Turing machine isn’t the only one that can compute this function. Here are two more:

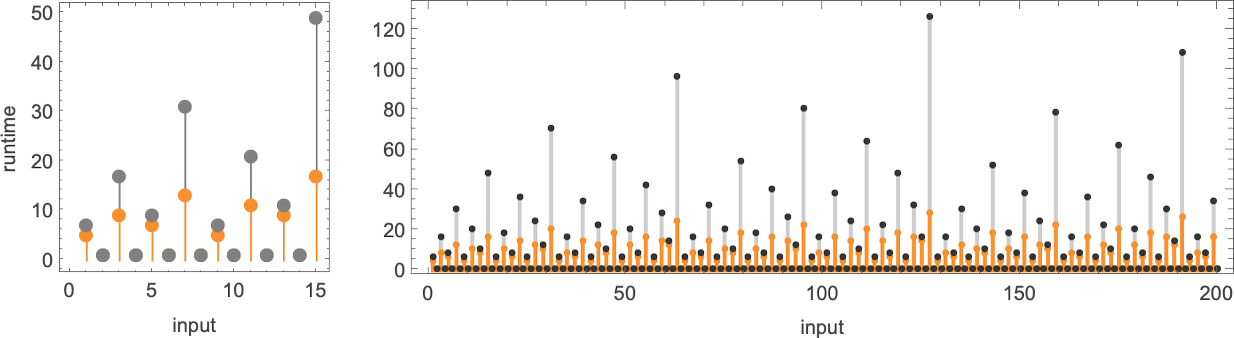

The outputs are the same as before, but the runtimes are different:

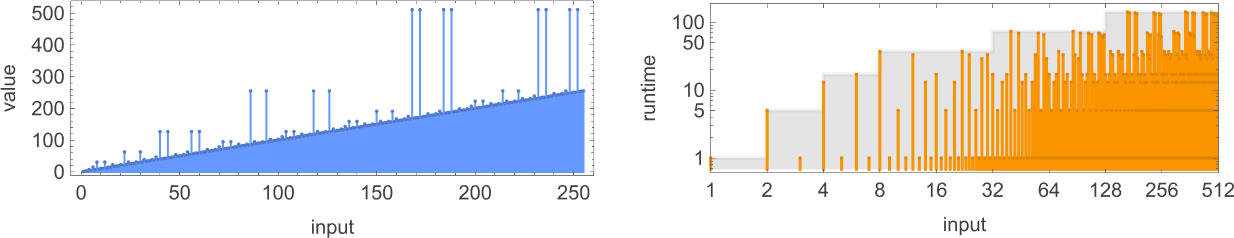

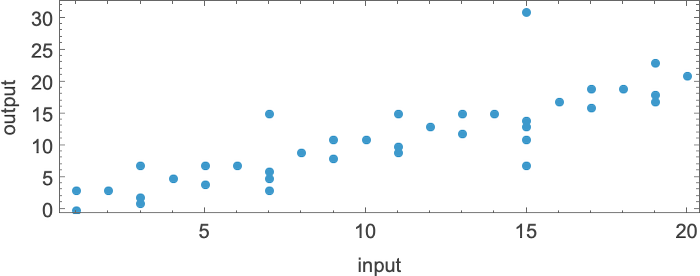

Indicating these respectively by ![]()

![]()

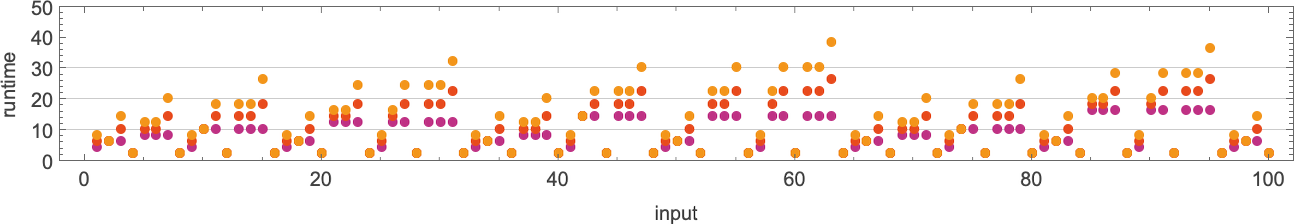

![]() and plotting them together, we see that there are definite trends—but no clear winner for “fastest program”:

and plotting them together, we see that there are definite trends—but no clear winner for “fastest program”:

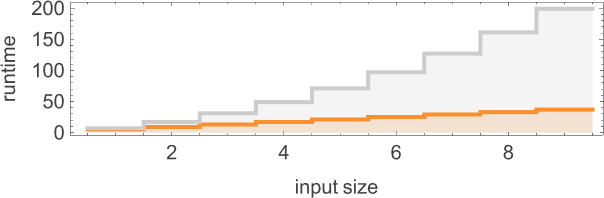

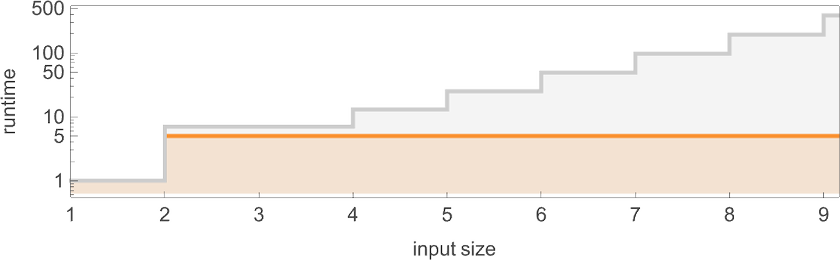

In computational complexity theory, it’s common to discuss how runtime varies with input size—which here means taking each block of inputs with a given number of digits, and just finding its maximum:

And what we see is that in this case the first Turing machine shown is “systematically faster” than the other two—and in fact provides the fastest way to compute this particular function among Turing machines of the size we’re using.

Since we’ll be dealing with lots of Turing machines here, it’s convenient to be able to specify them just with numbers—and we’ll do it the way TuringMachine in the Wolfram Language does. And with this setup, the machines we’ve just considered have numbers 261, 3333 and 1285.

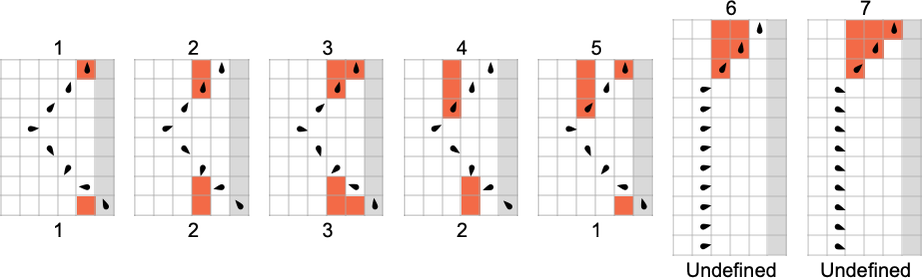

In thinking about functions computed by Turing machines, there is one immediate subtlety to consider. We’ve said that we find the output by reading off what’s on the Turing machine tape when the Turing machine stops. But what if the machine never stops? (Or in our case, what if the head of the Turing machine never reaches the right-hand end?) Well, then there’s no output value defined. And in general, the functions our Turing machines compute will only be partial functions—in the sense that for some of their inputs, there may be no output value defined (as here for machine 2189):

When we plot such partial functions, we’ll just have a gap where there are undefined values:

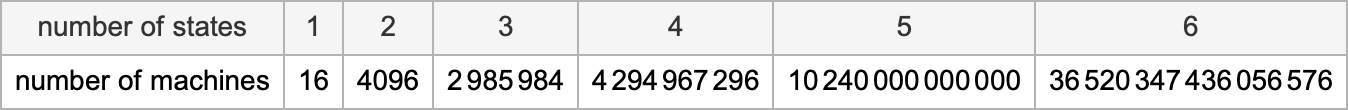

In what follows, we’ll be exploring Turing machines of different “sizes”. We’ll assume that there are two possible colors for each position on the tape—and that there are s possible states for the head. The total number of possible Turing machines with k = 2 colors and s states is (2ks)ks—which grows rapidly with s:

For any given function we’ll then be able to ask what machine (or machines) up to a given size compute it the fastest. In other words, by explicitly studying possible Turing machines, we’ll be able to establish an absolute lower bound on the computational difficulty of computing a function, at least when that computation is done by a Turing machine of at most a given size. (And, yes, the size of the Turing machine can be thought of as characterizing its “algorithmic information content”.)

In traditional computational complexity theory, it’s usually been very difficult to establish lower bounds. But our ruliological approach here will allow us to systematically do it (at least relative to machines of a given size, i.e. with given algorithmic information content). (It’s worth pointing out that if a machine is big enough, it can include a lookup table for any number of cases of any given function—making questions about the difficulty of computing at least those cases rather moot.)

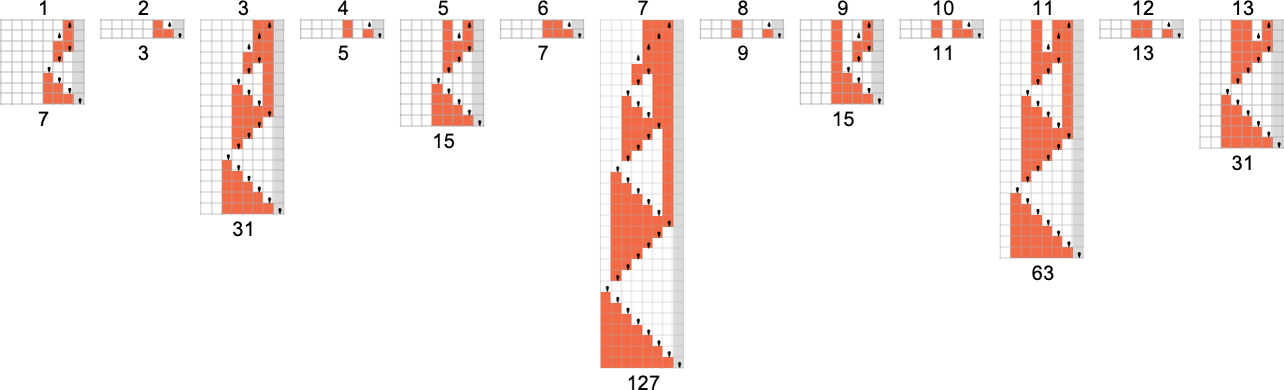

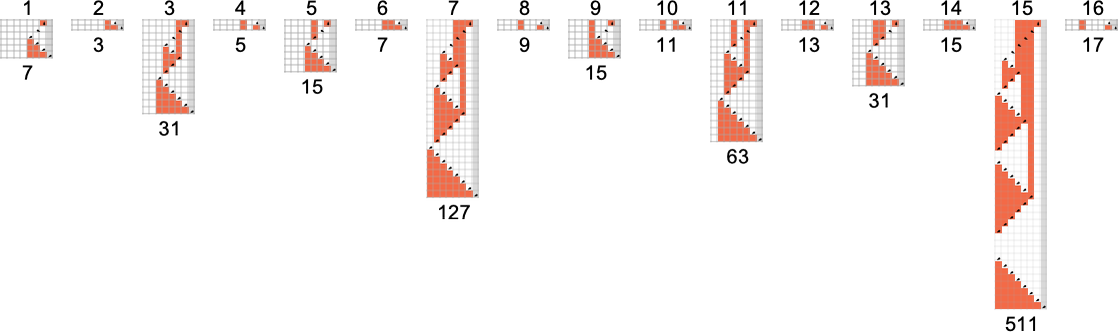

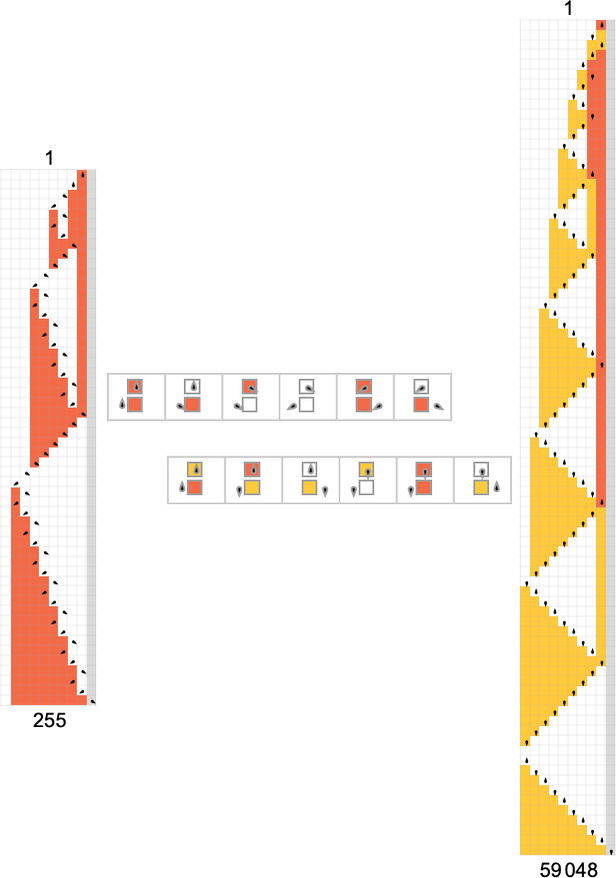

The s = 1, k = 2 Turing Machines

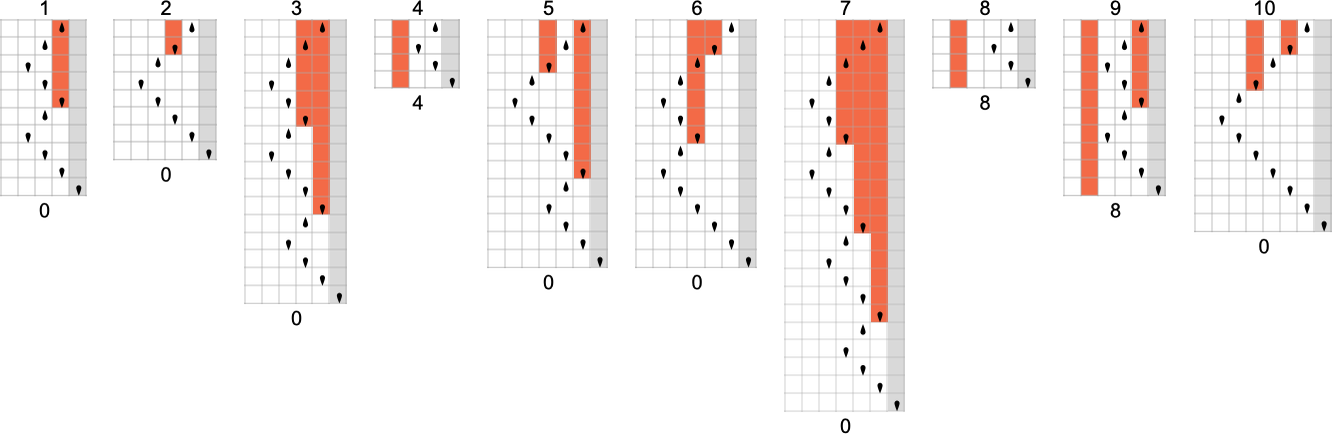

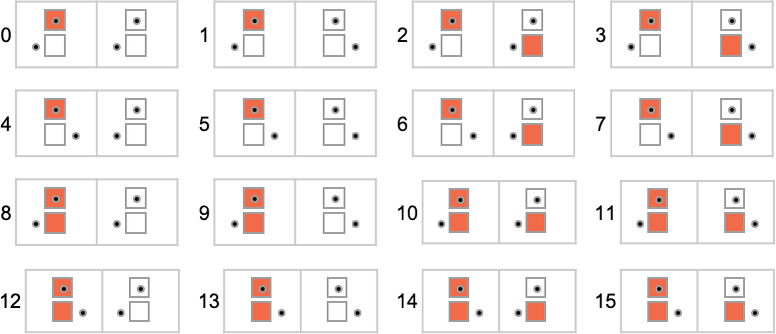

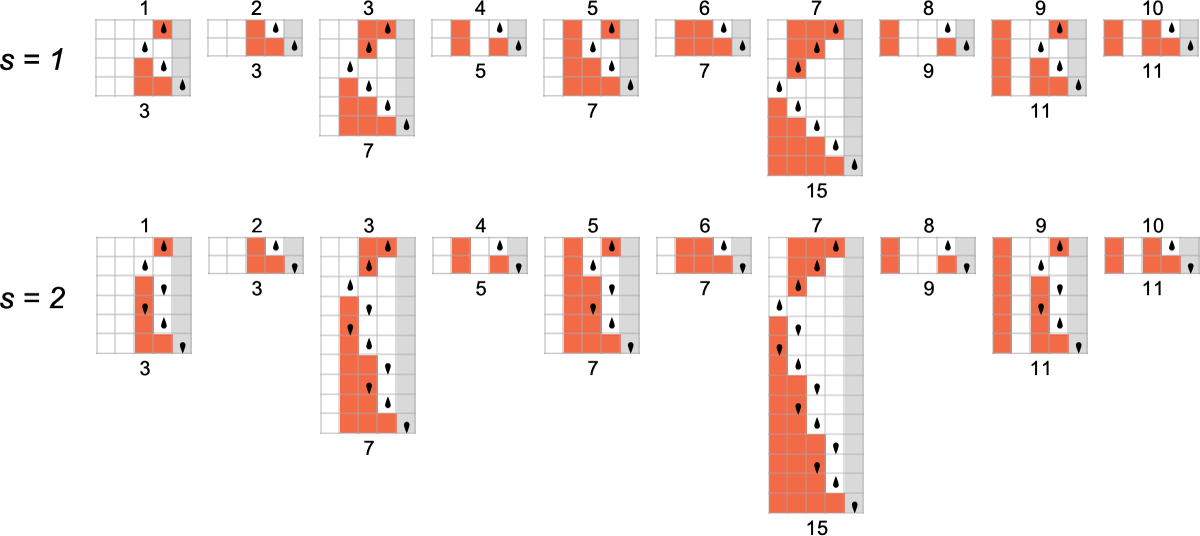

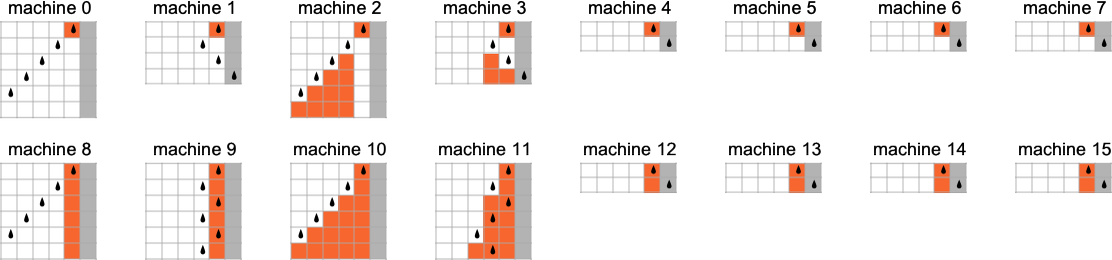

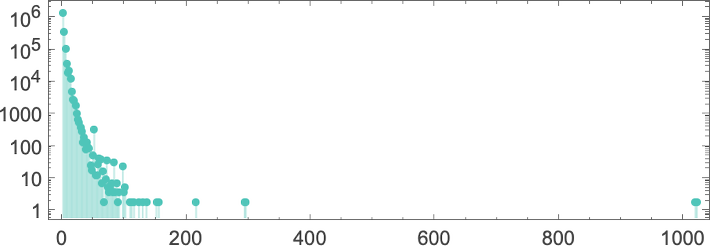

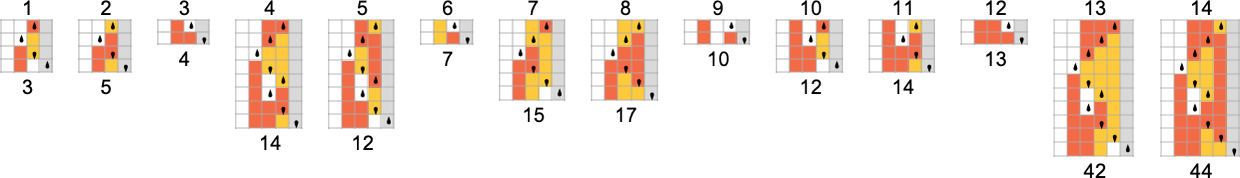

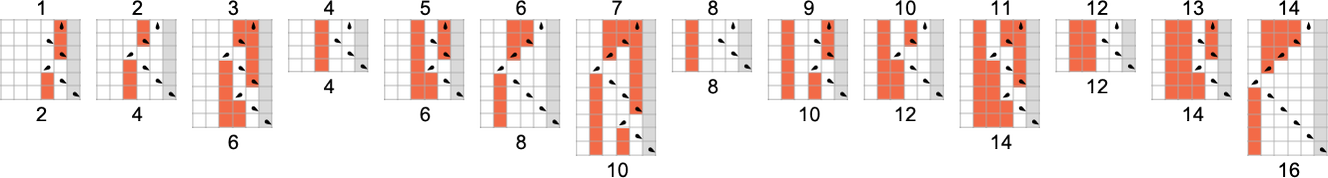

To begin our systematic investigation of possible programs, let’s consider what is essentially the simplest possible case: Turing machines with one state and two possible colors of cells on their tape

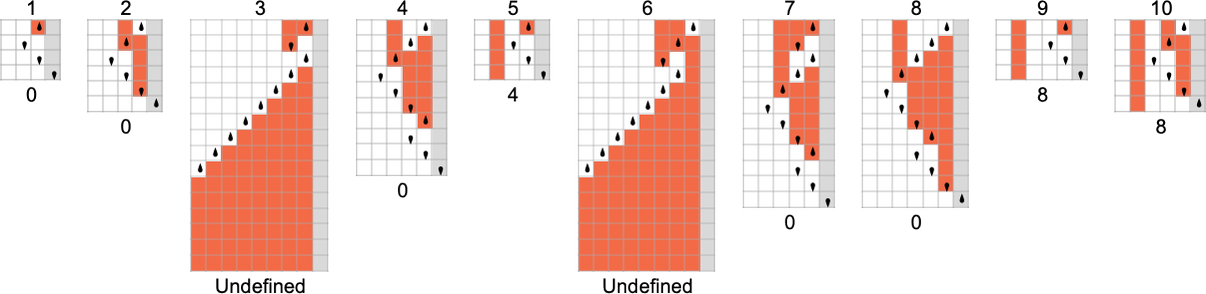

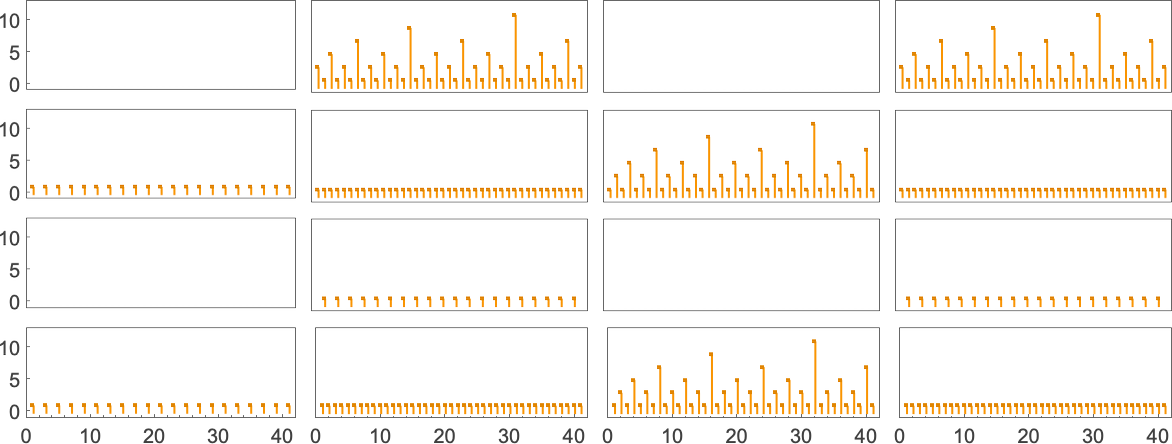

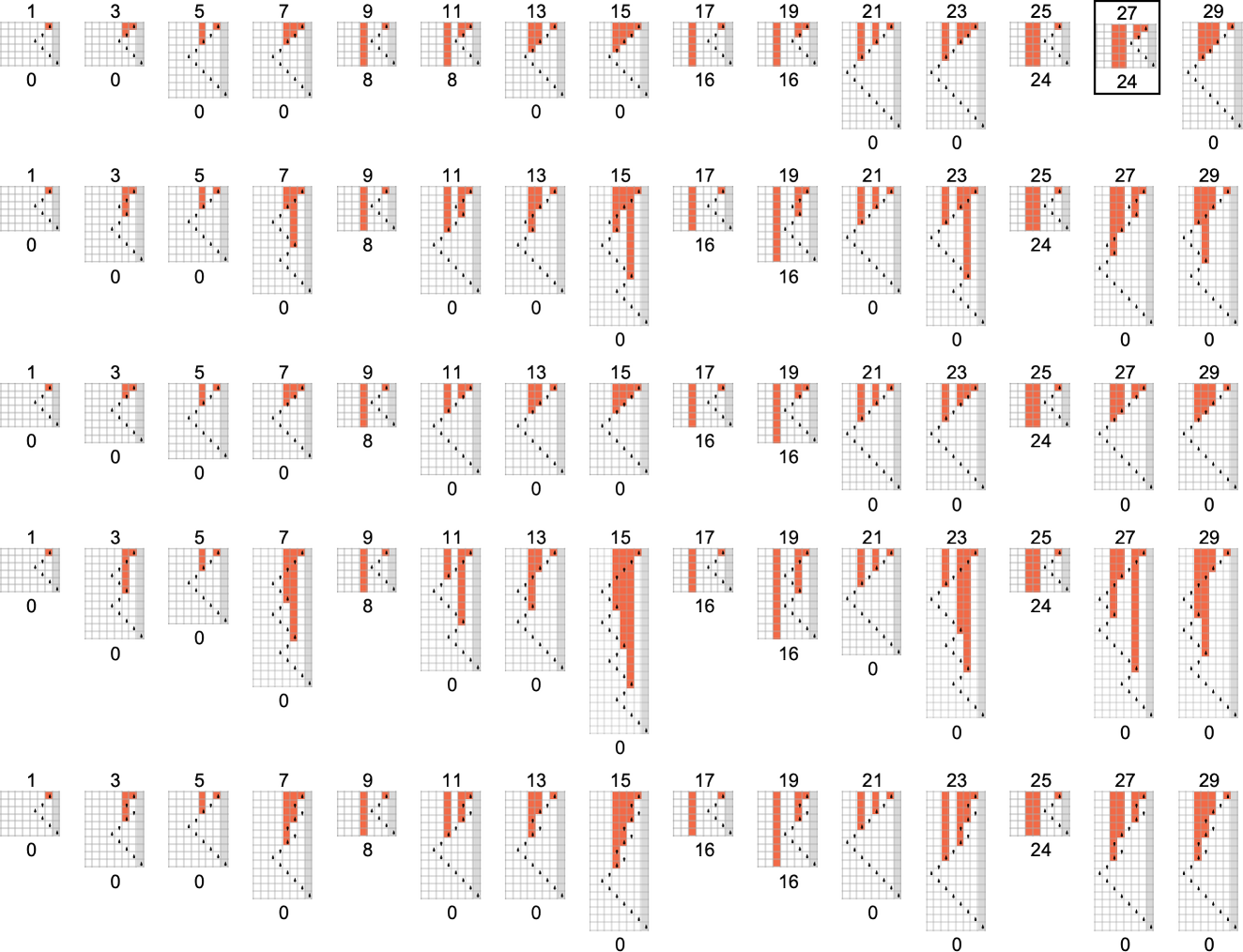

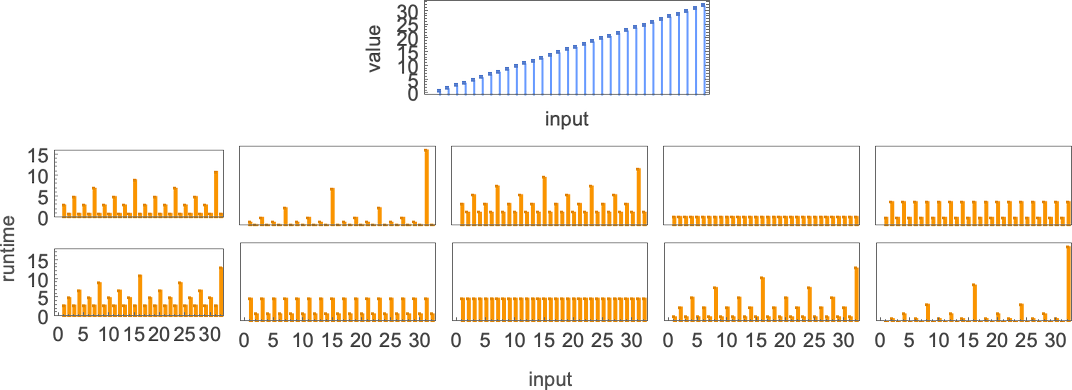

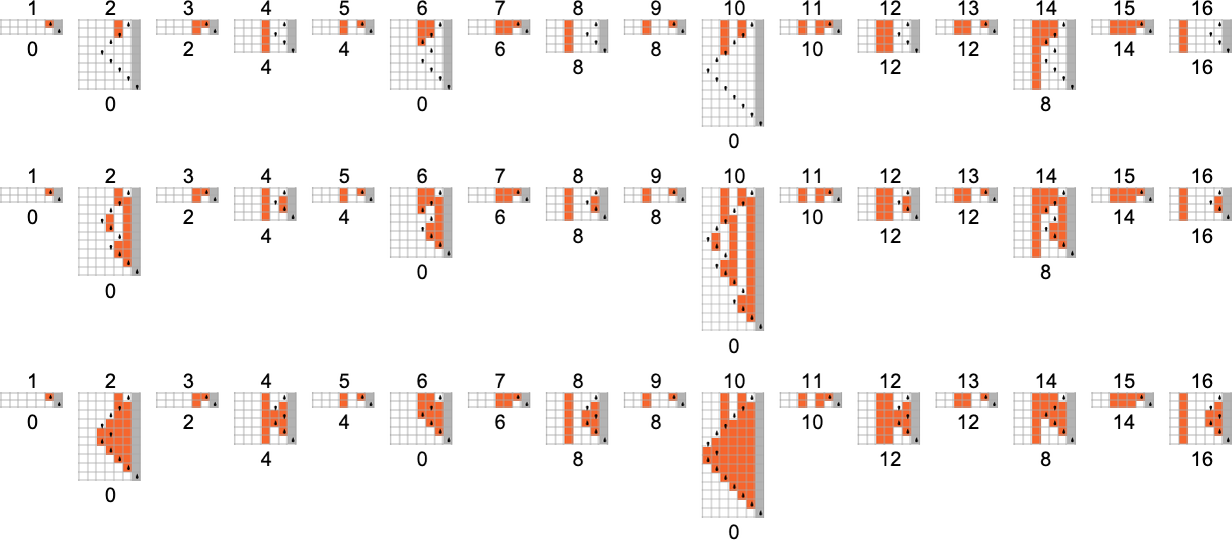

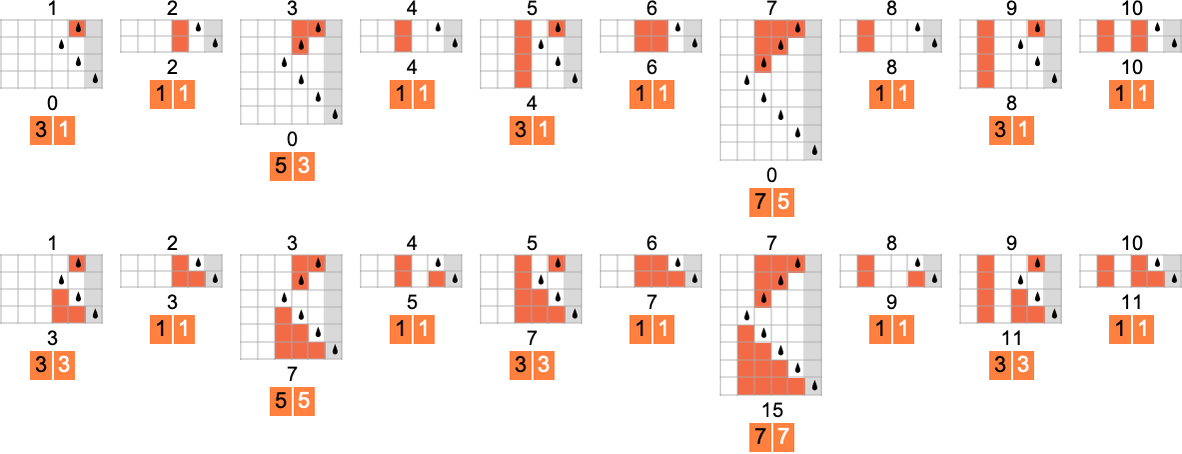

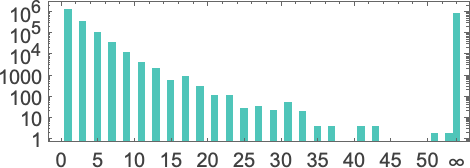

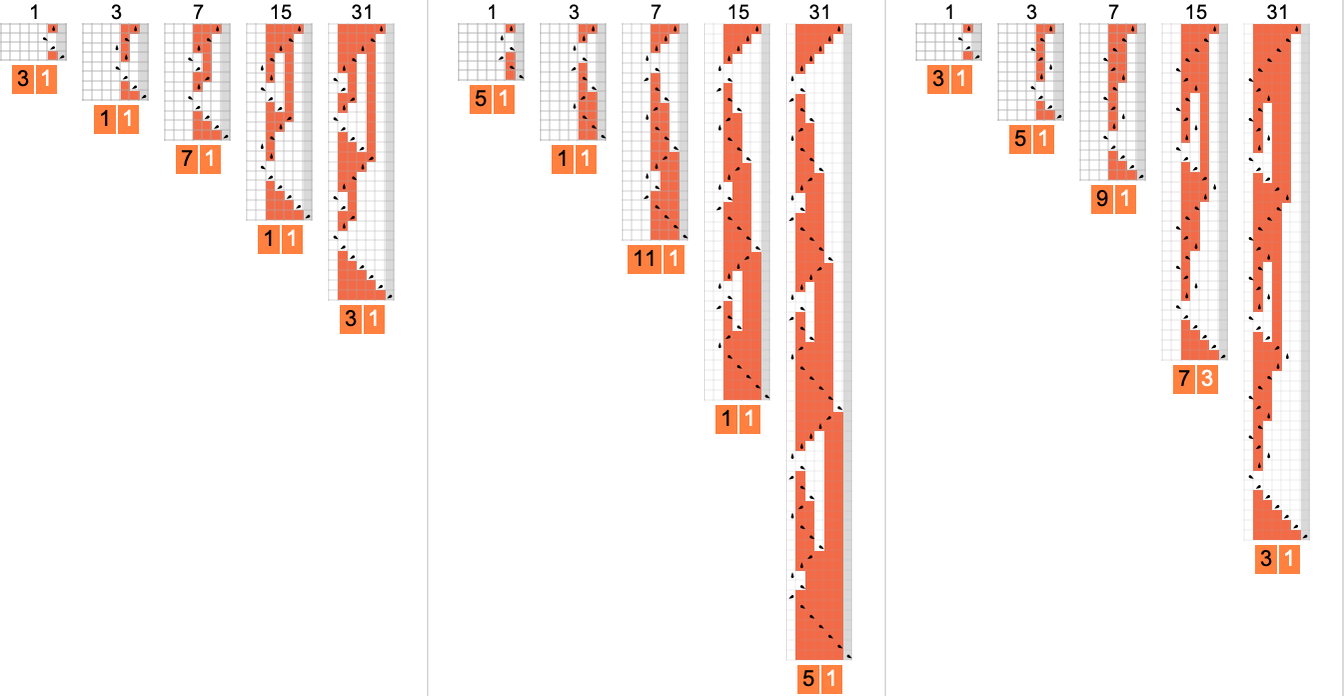

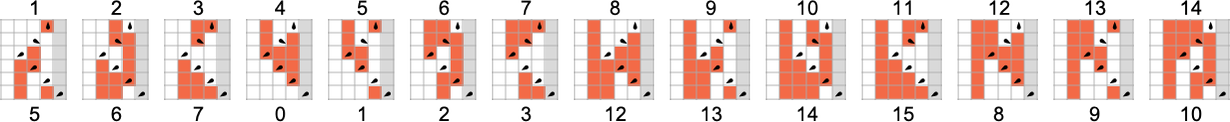

Here’s what each of these machines does for successive integer inputs:

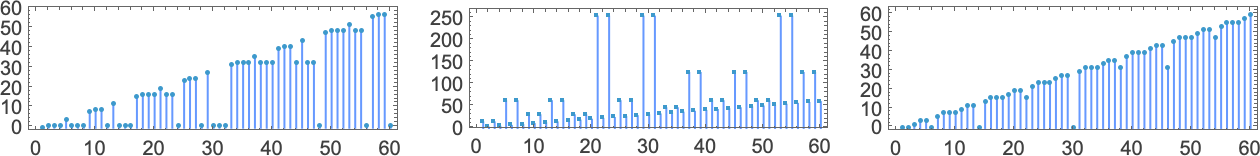

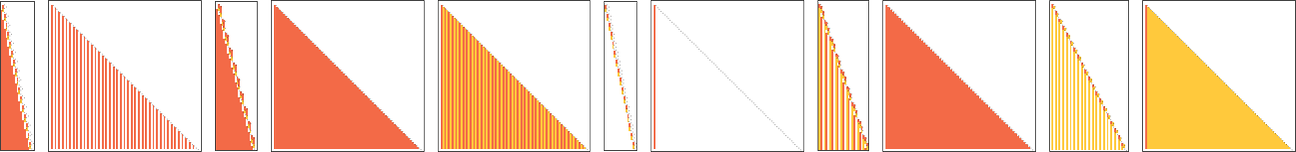

Looking at the outputs in each case, we can plot the functions these compute:

And here are the corresponding runtimes:

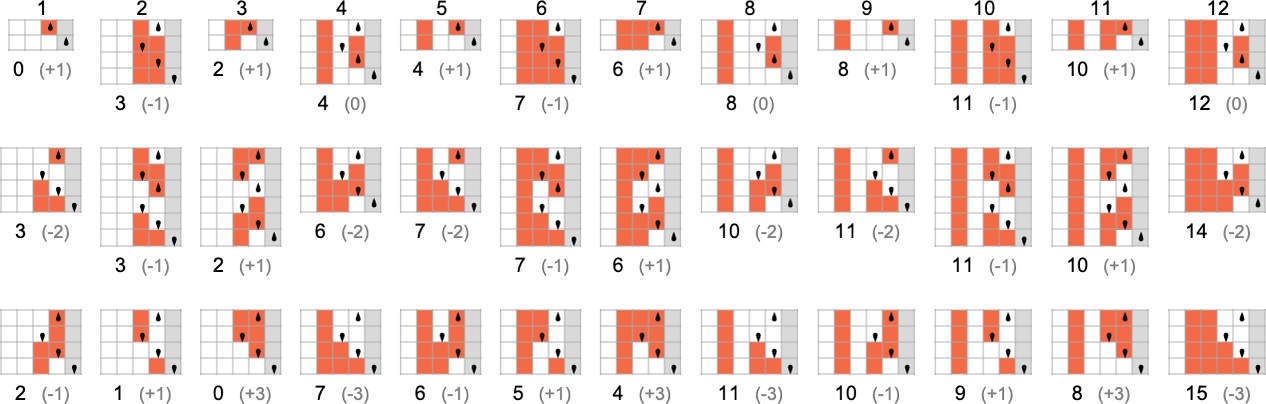

Out of all 16 machines, 8 compute total functions (i.e. the machines always terminate, so the values of the functions are defined for every input), and 8 don’t. Four machines produce “complicated-looking” functions; an example is machine 14, which computes the function:

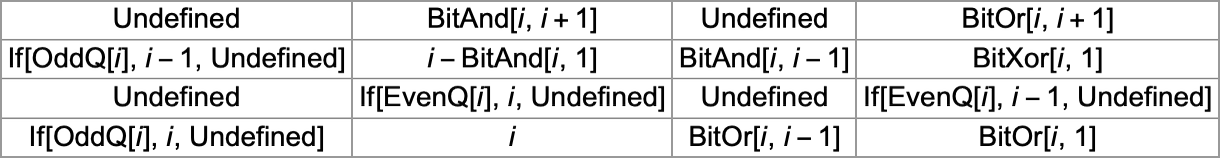

There are a variety of representations for this function, including

and:

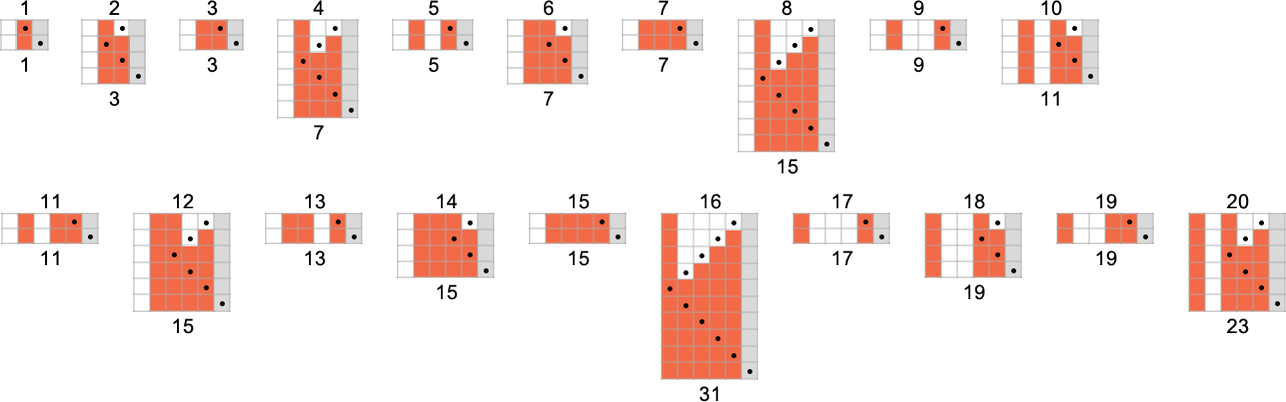

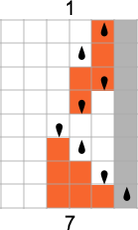

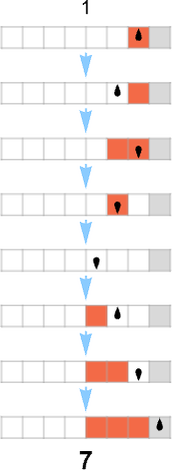

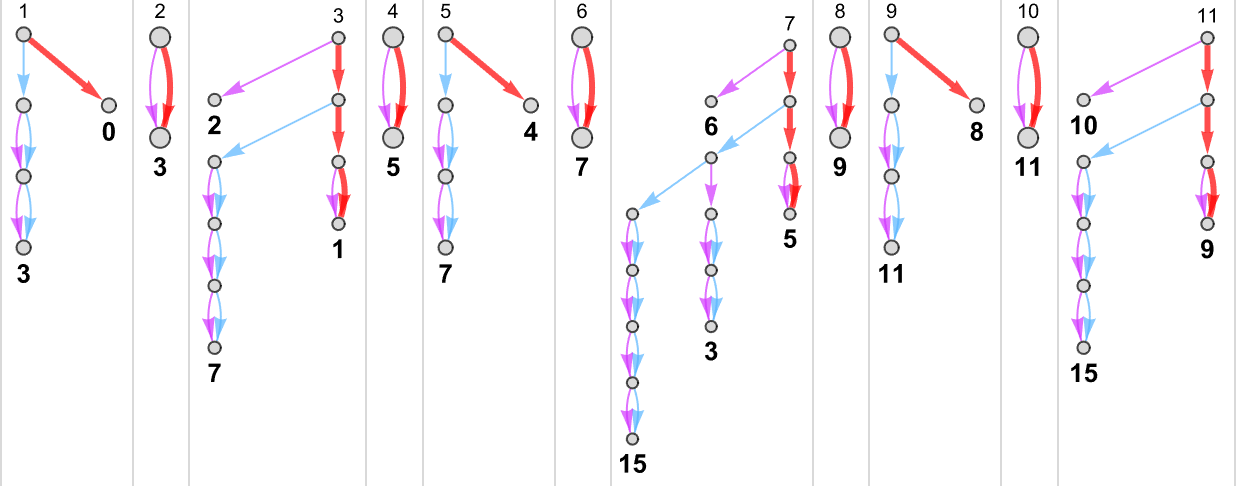

The way the function is computed by the Turing machine is

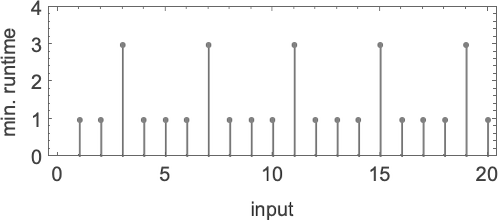

and the runtime is given by

which is simply:

For input of size n, this implies the worst-case time complexity for computing this function is

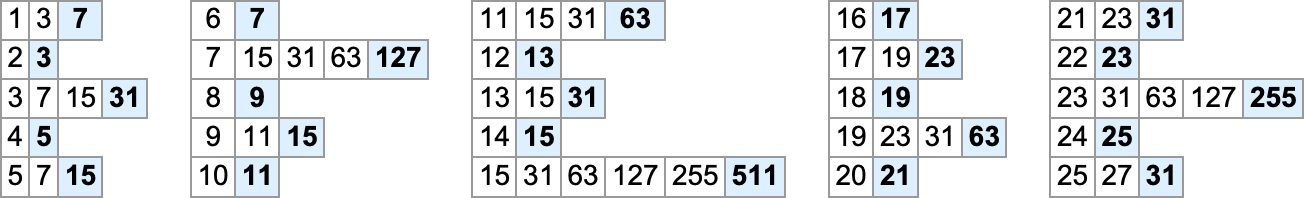

Each one of the 1-state machines works at least slightly differently. But in the end, all of them are simple enough in their behavior that one can readily give a “closed-form formula” for the value of f[i] for any given i:

One thing that’s notable is that—except in the trivial case where all values are undefined—there are no examples among

s = 2, k = 2 Turing Machines

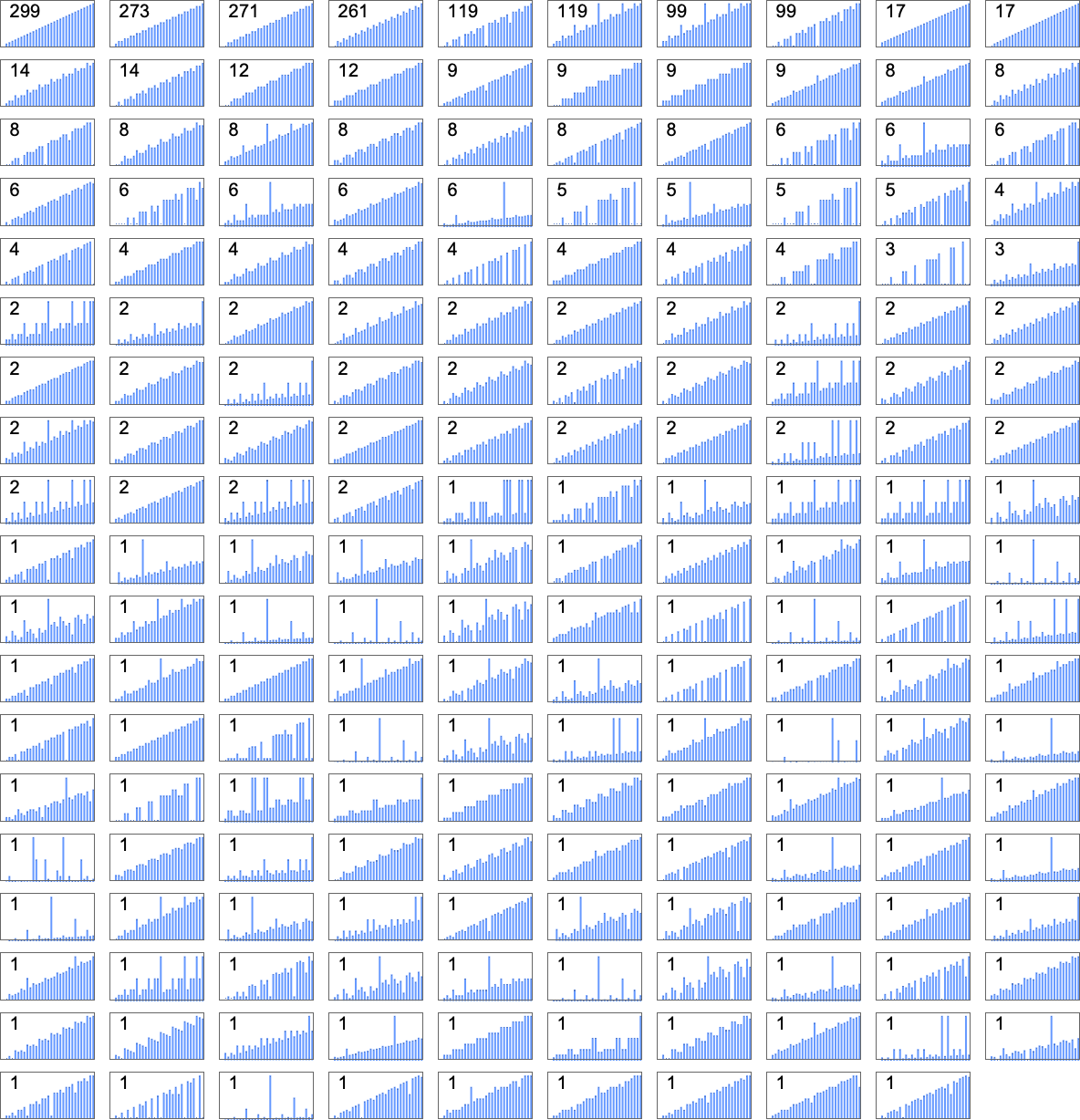

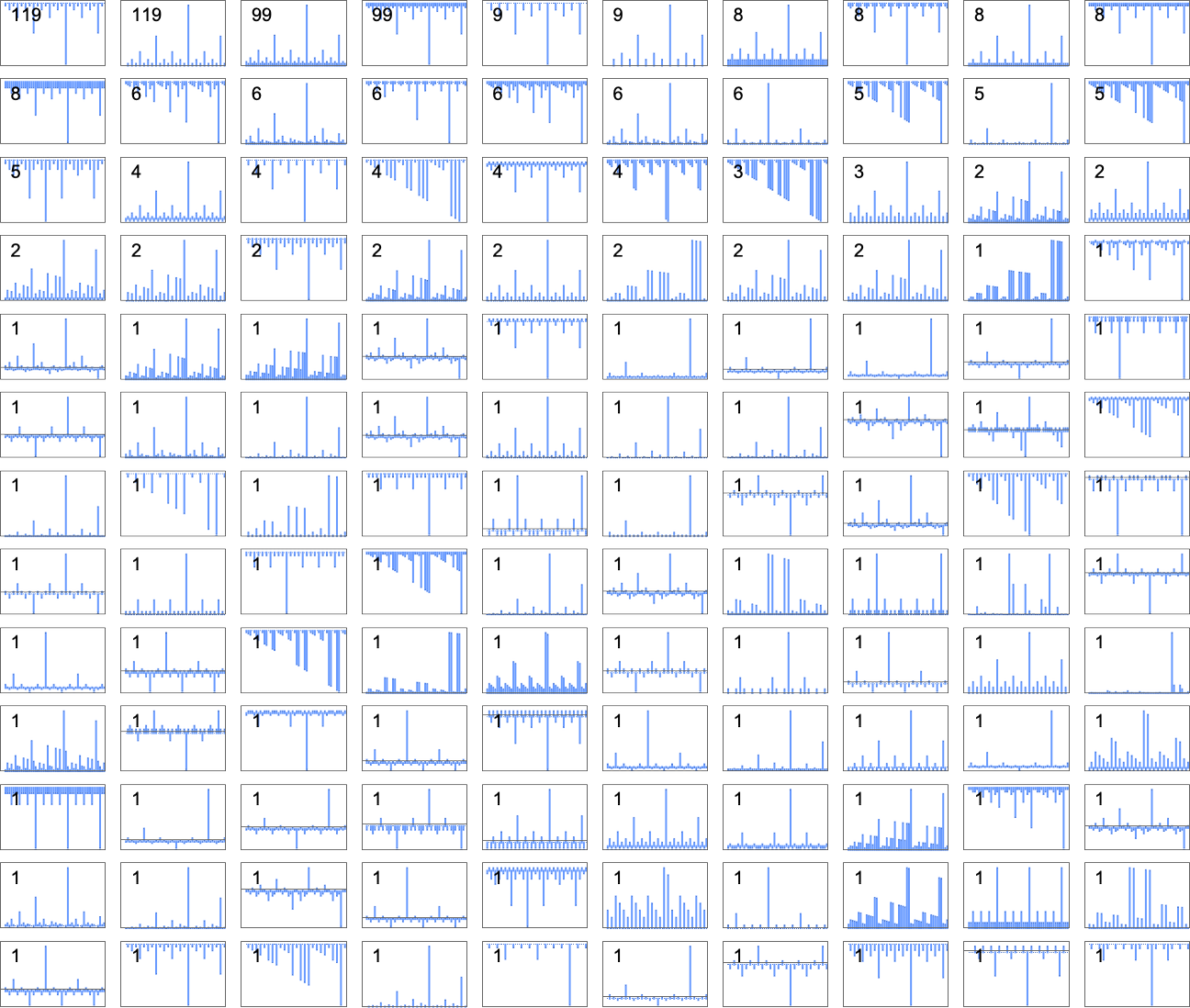

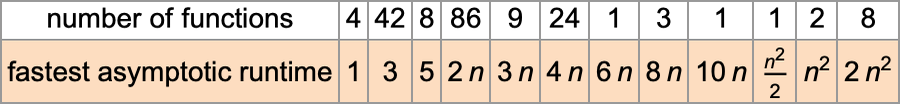

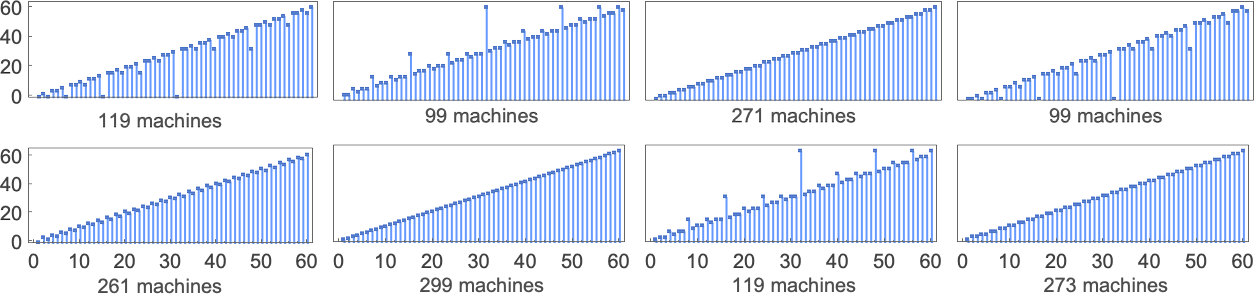

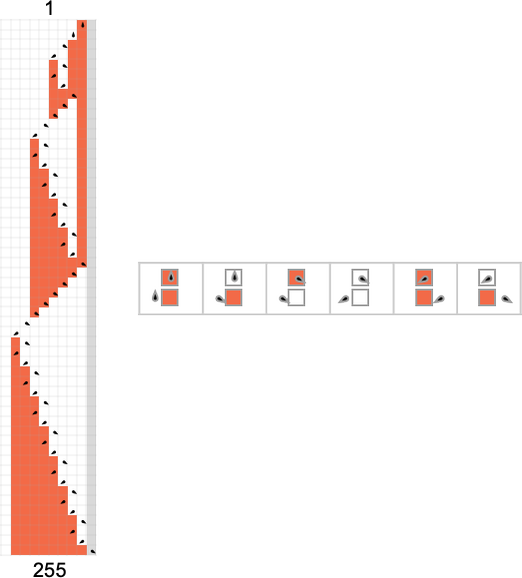

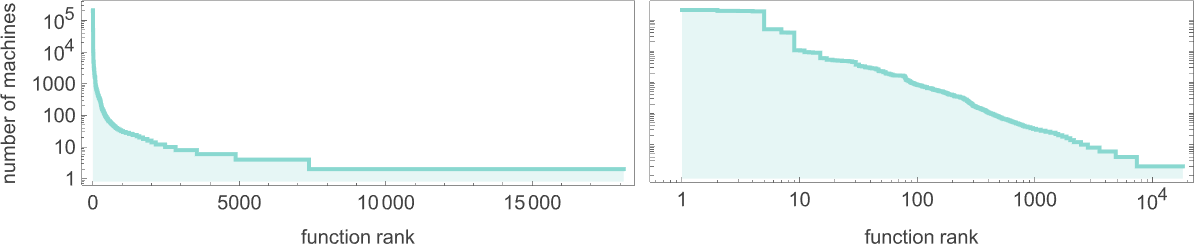

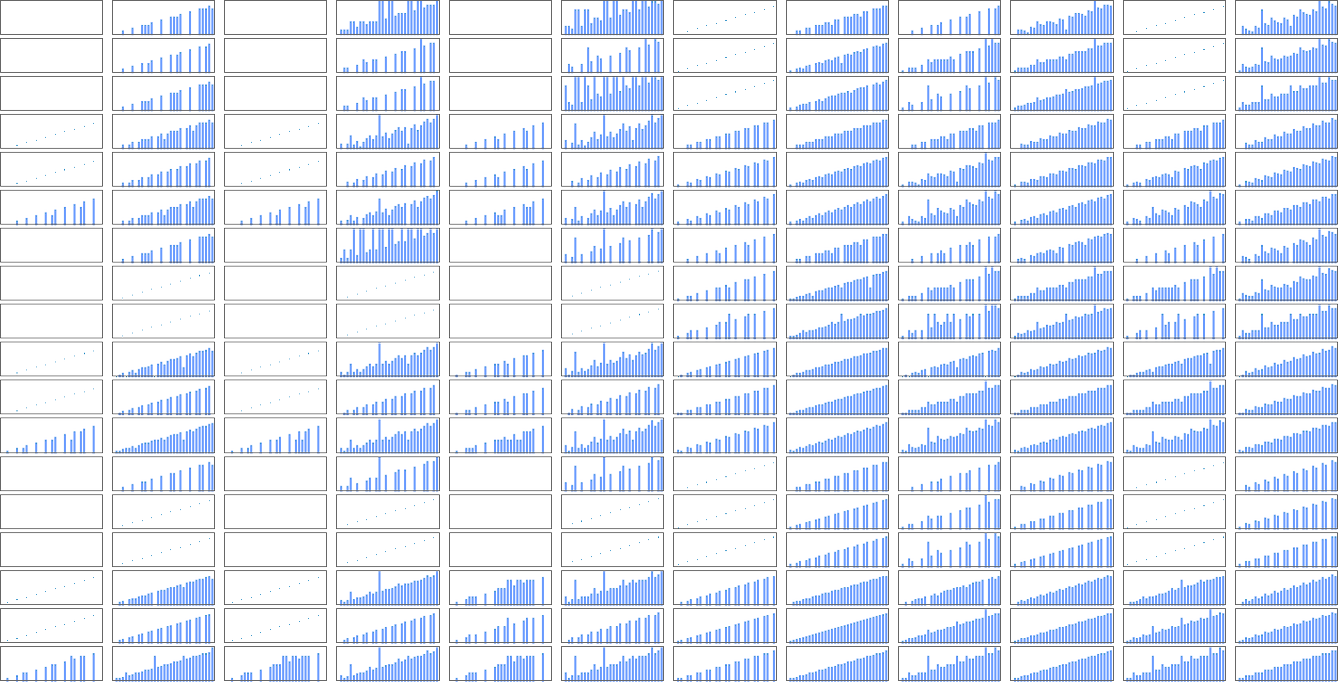

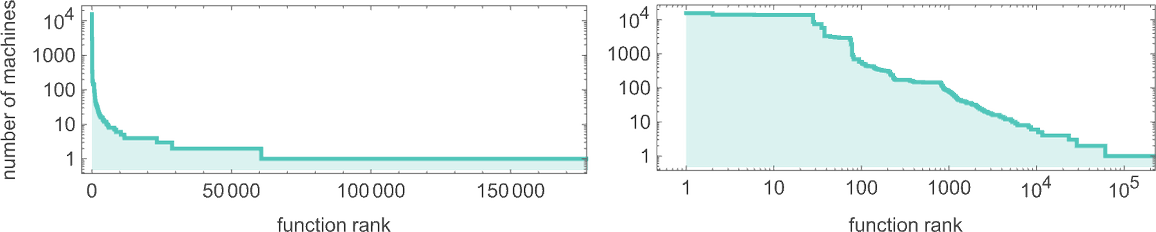

There are a total of 4096 possible 2-state, 2-color Turing machines. Running all these machines, we find that they compute a total of 350 distinct functions—of which 189 are total. Here are plots of these distinct total functions—together with a count of how many machines generate them (altogether 2017 of the 4096 machines always terminate, and therefore compute total functions):

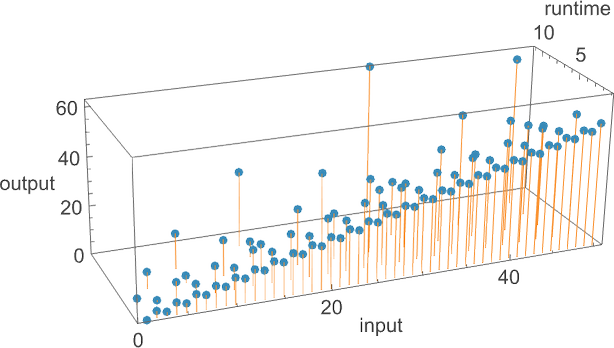

Plotting the values of all these functions in 3D, we see that the vast majority have values f[i] that are close to their inputs i—indicating that in a sense the Turing machines usually “don’t do much” to their input:

To see more clearly what the machines “actually do”, we can look at the quantity

though in 6 cases it is 2, and in 3 cases (which include the “most popular” case

Dropping periodic cases, the remaining distinct

Some of what we see here is similar to the 1-state case. An example of different behavior occurs for machine 2223

which gives for

In this case f[i] turns out to be expressible simply as

or:

Another example is machine 2079

which gives for

This function once again turns out to be expressible in “closed form”:

Some functions grow rapidly. For example, machine 3239

has values:

These have the property that

There are many subtleties even in dealing with 2-state Turing machines. For example, different machines may “look like” they’re generating the same function f[i] up to a certain value of i, and only then deviate. The most extreme example of such a “surprise” among machines generating total functions occurs among:

Up to

What about partial functions? At least for 2-state machines, if undefined values in f[i] are ever going to occur, they always already occur for small i. The “longest holdouts” are machines 1960 and 2972, which are both first undefined for input 8

but which “become undefined” in different ways: in machine 1960, the head systematically moves to the left, while in machine 2972, it moves periodically back and forth forever, without ever reaching the right-hand end. (Despite their different mechanisms, both rules share the feature of being undefined for all inputs that are multiples of 8.)

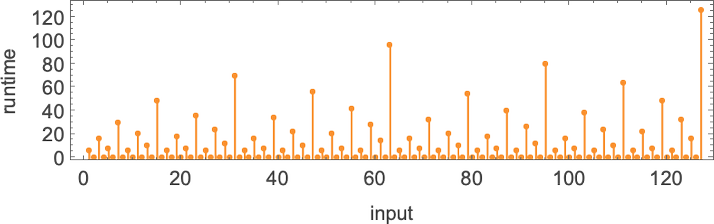

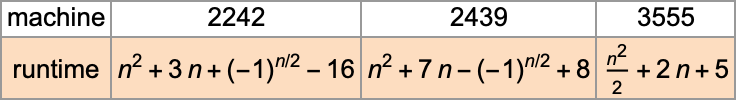

Runtimes in s = 2, k = 2 Machines

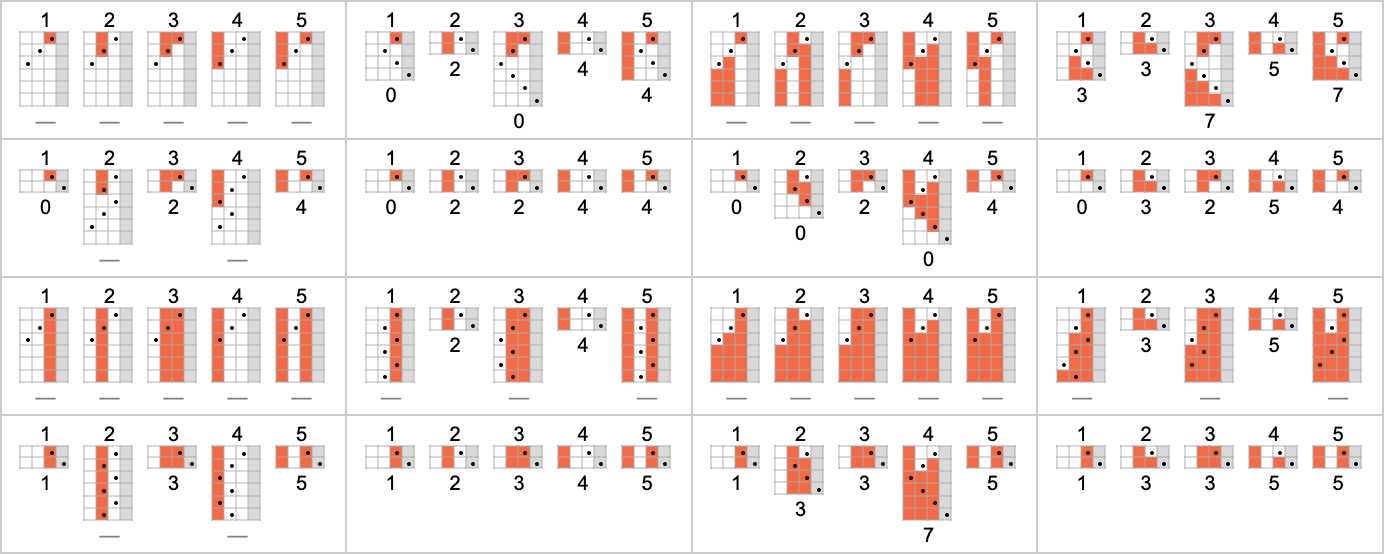

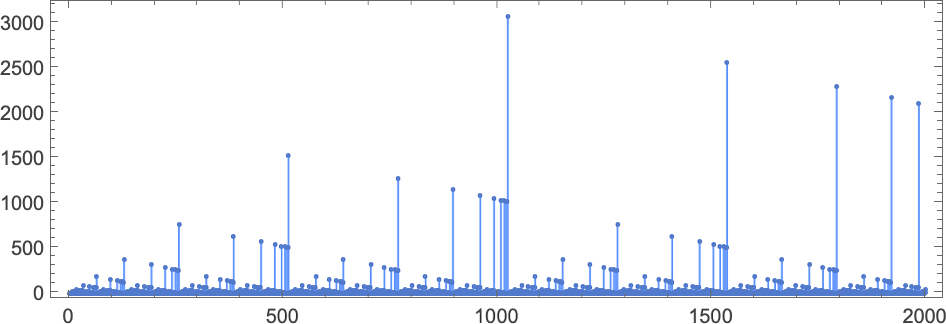

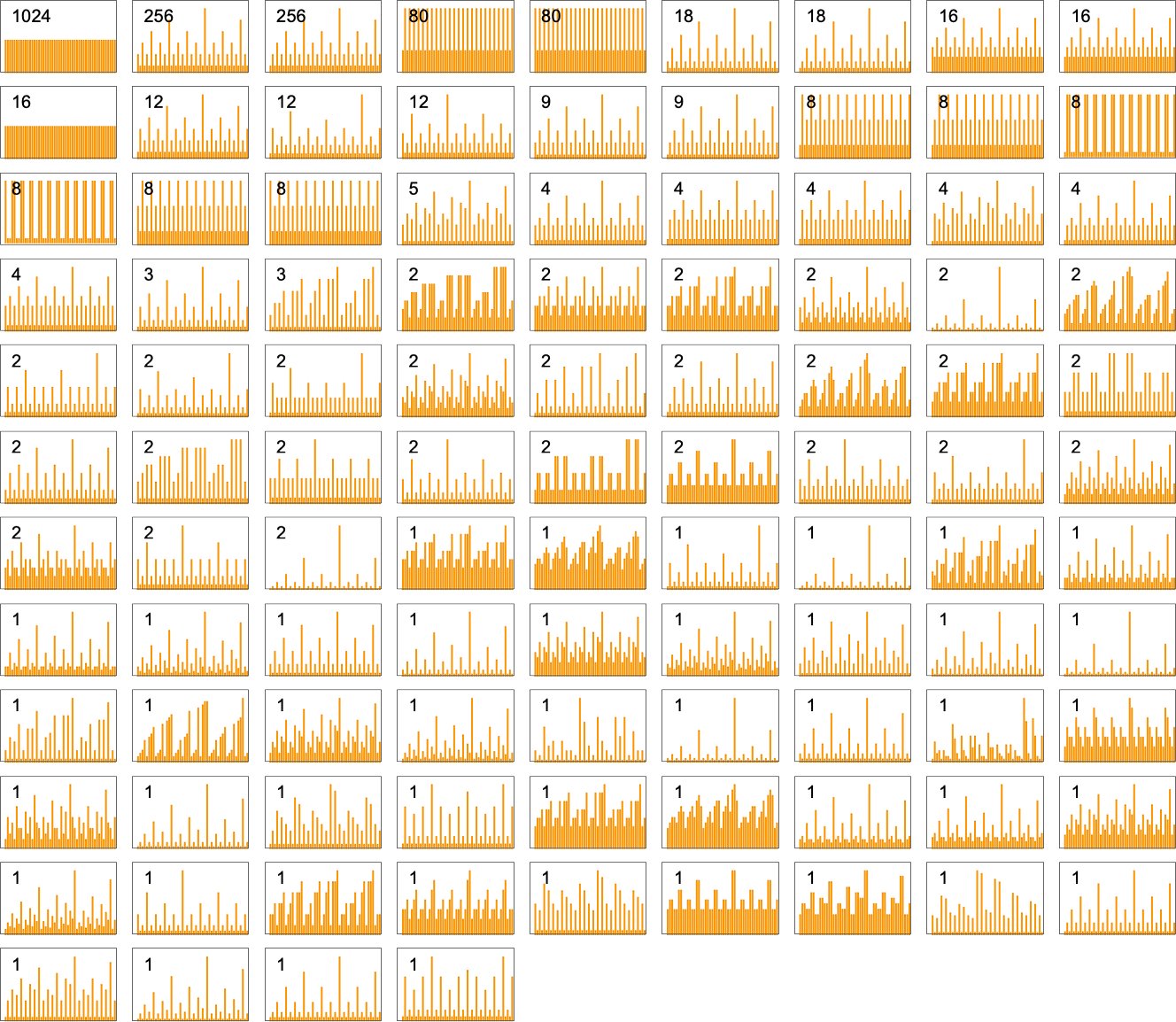

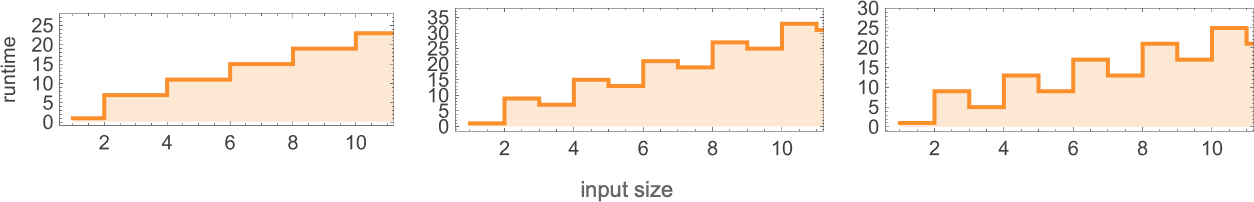

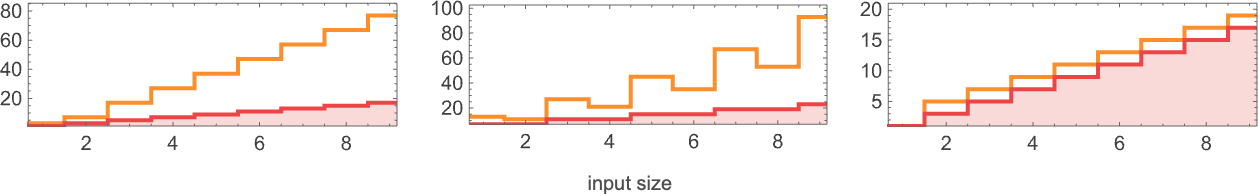

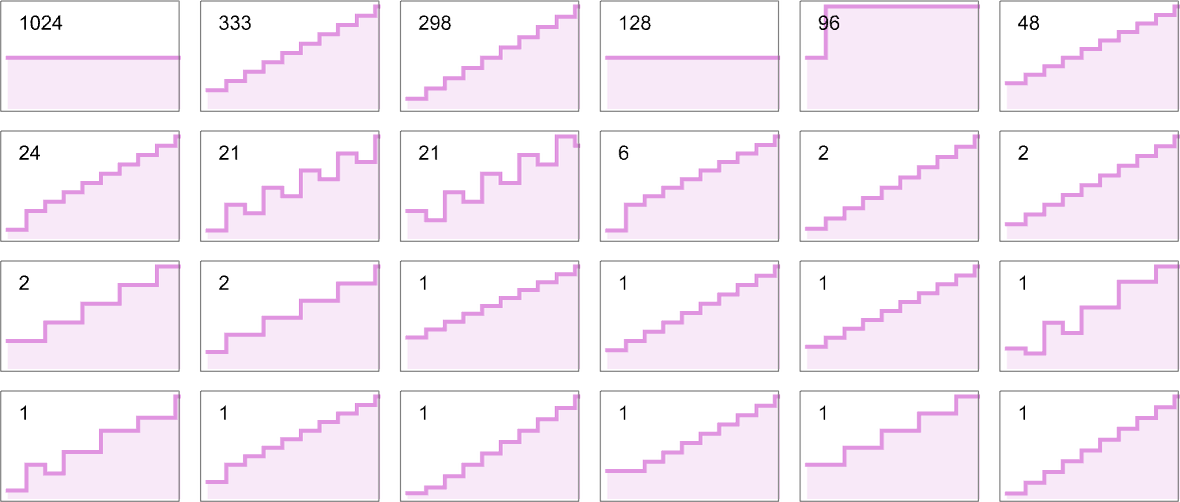

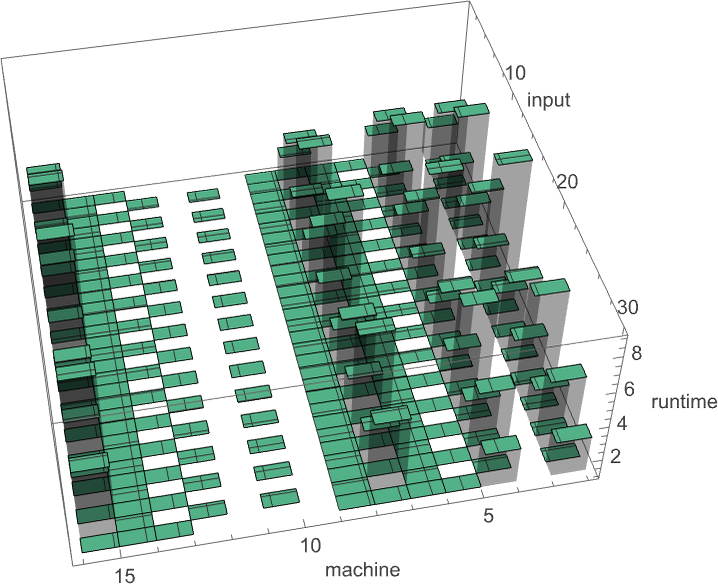

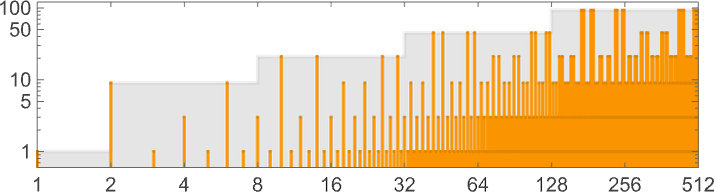

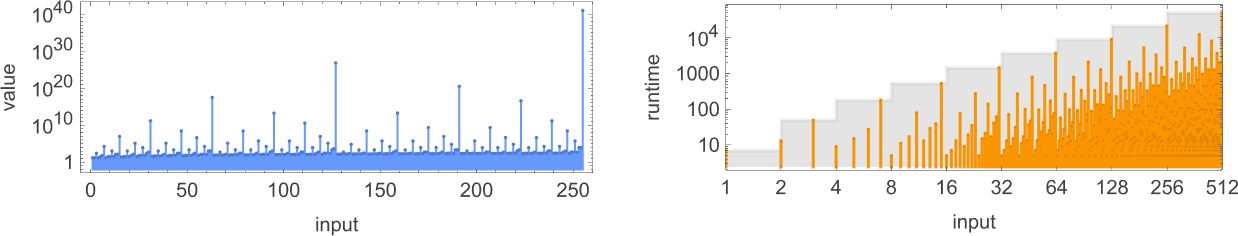

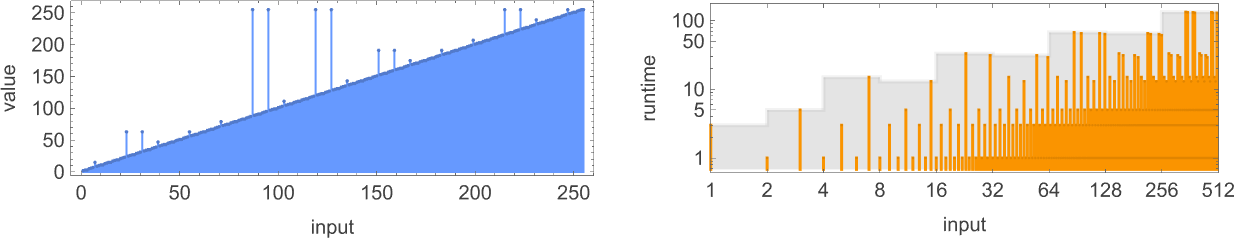

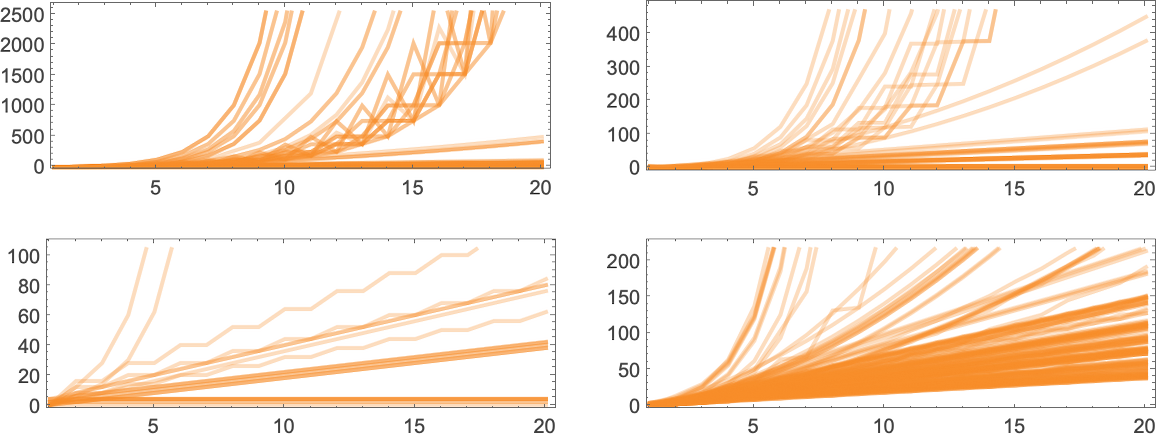

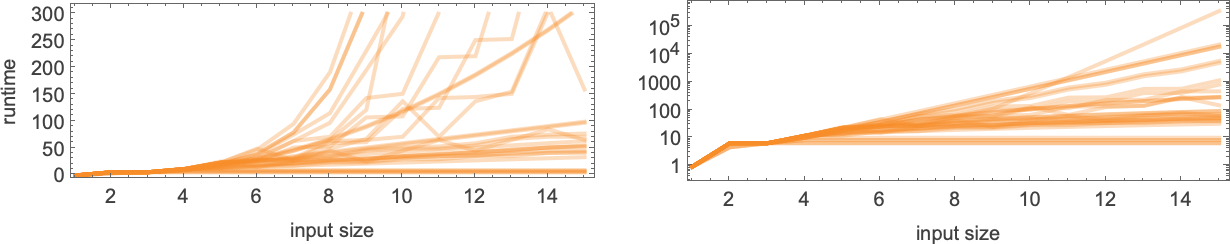

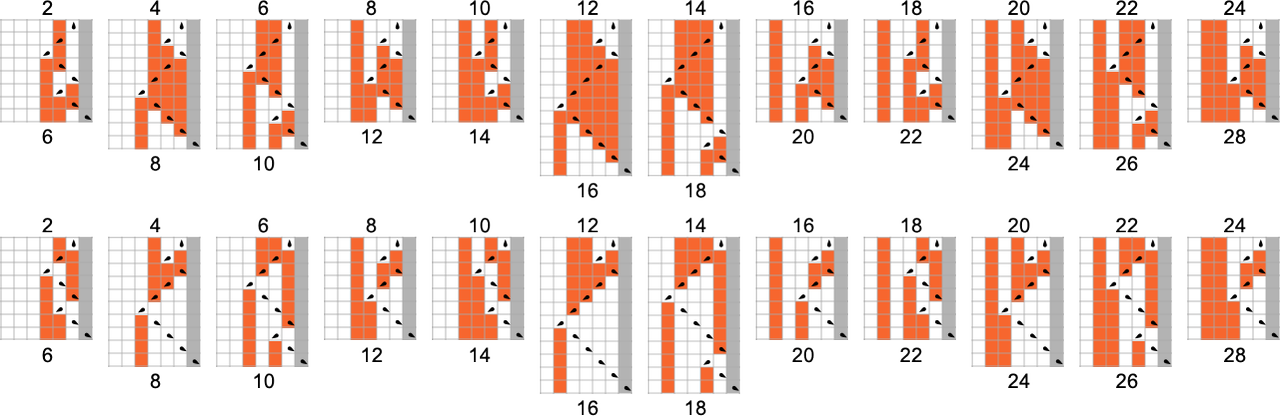

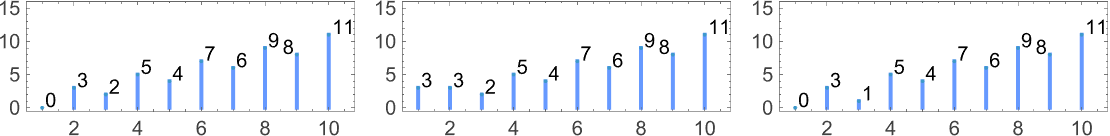

What about runtimes? If a function f[i] is computed by several different Turing machines, the details of how it’s computed by each machine will normally be at least slightly different. Still, in many cases the mechanisms are similar enough that their runtimes are the same. And in the end, among all the 2017 machines that compute our 189 distinct total functions, there are only 103 distinct “profiles” of runtime vs. input (and indeed many of these are very similar):

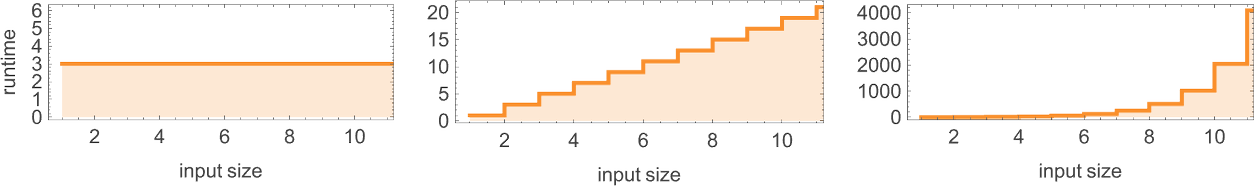

The picture gets simpler if, rather than plotting runtimes for each specific input value, we instead plot the worst-case runtime for all inputs of a given size. (In effect we’re plotting against IntegerLength[i, 2] or Ceiling[Log2[i + 1]].) There turn out to be just 71 distinct profiles for such worst-case time complexity

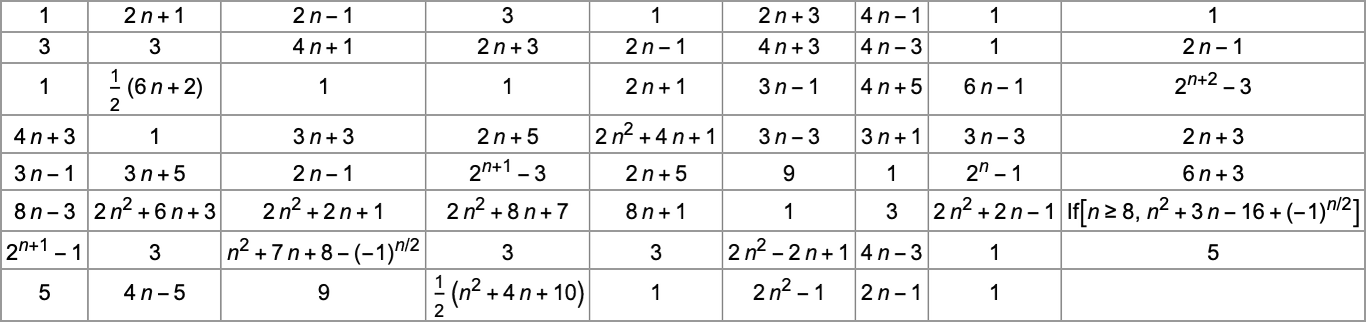

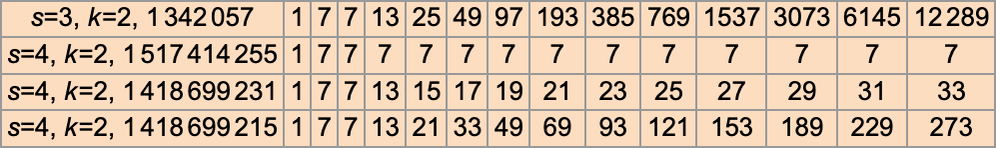

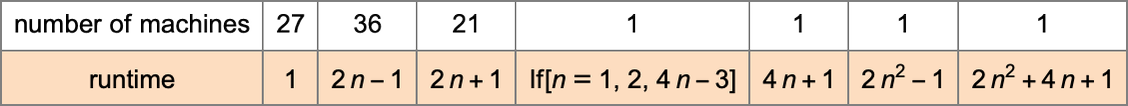

and indeed all of these have fairly simple closed forms—which for even n are (with directly analogous forms for odd n):

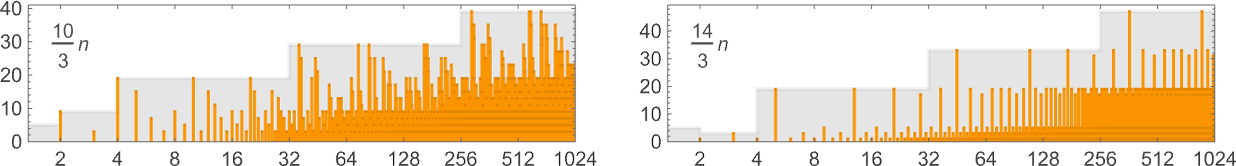

If we consider the behavior of these worst-case runtimes for large input lengths n, we find that fairly few distinct growth rates occur—notably with linear, quadratic and exponential cases, but nothing in between:

The machines with the fastest growth

For a size-n input, the maximum value of the function is just the maximum integer with n digits, or

And at these maxima, the machine is effectively operating like a binary counter, generating all the states it can, with the head moving in a very regular nested pattern:

It turns out that for

Of the 8 machines with runtimes growing like

The two machines with asymptotic runtime growth

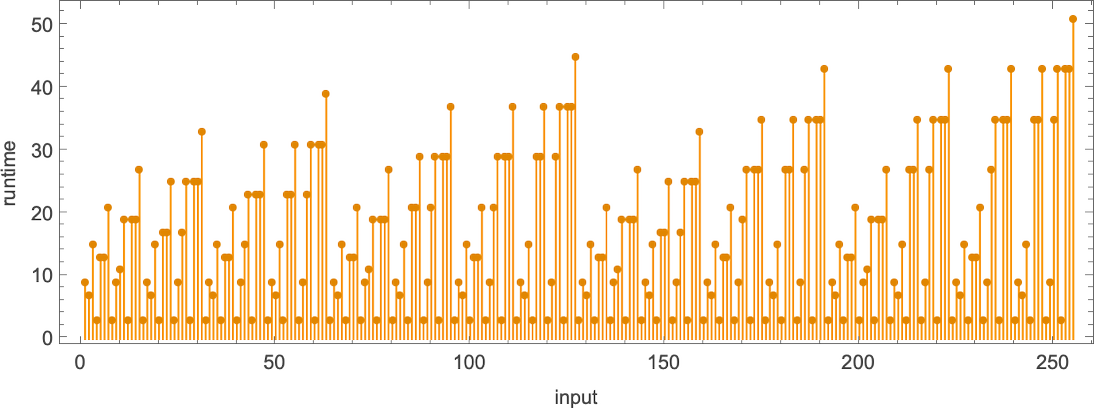

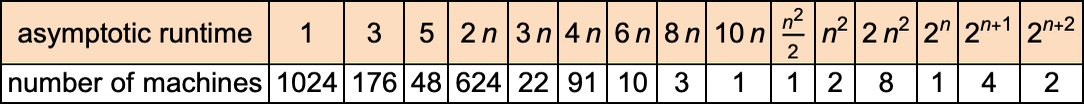

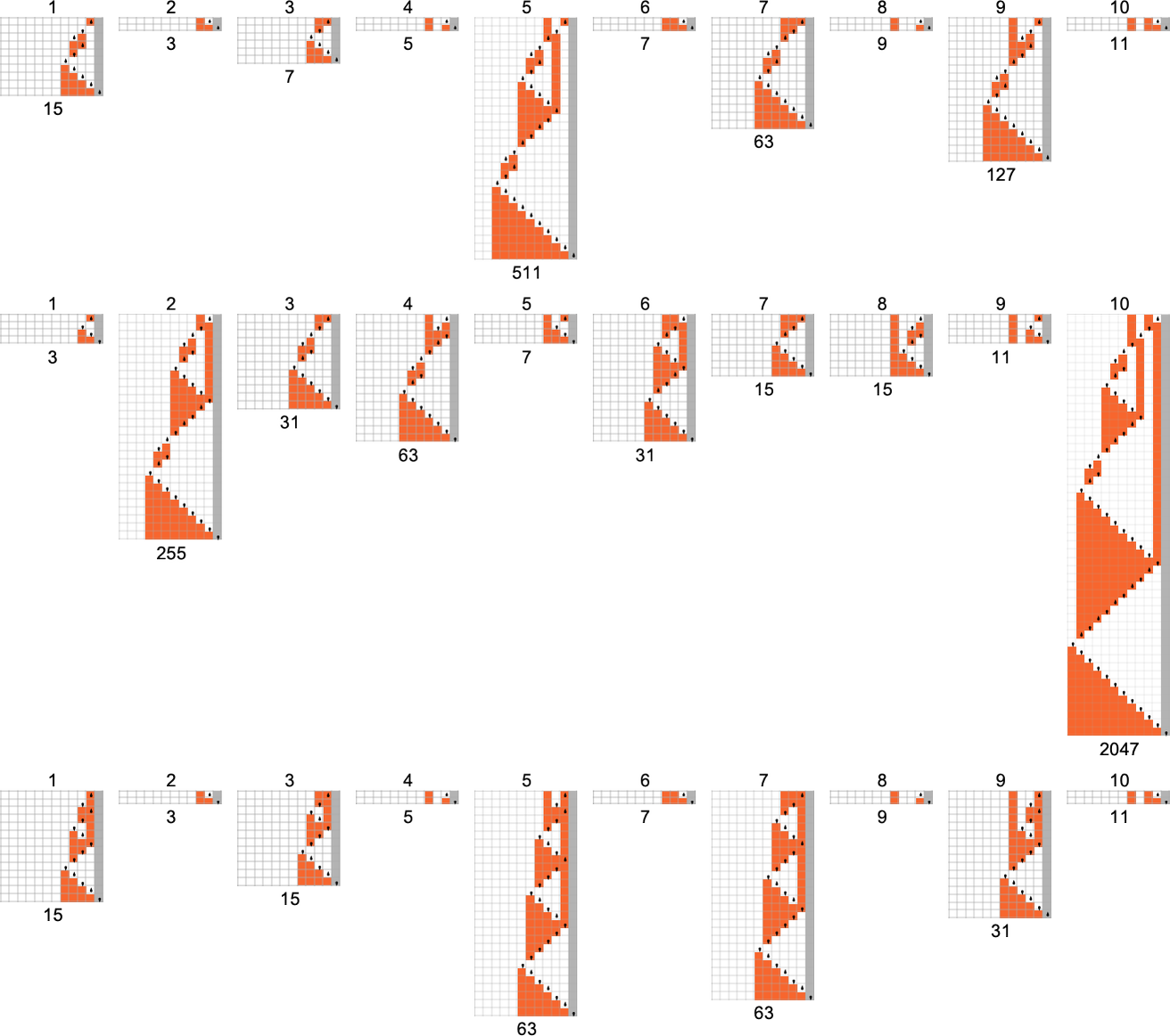

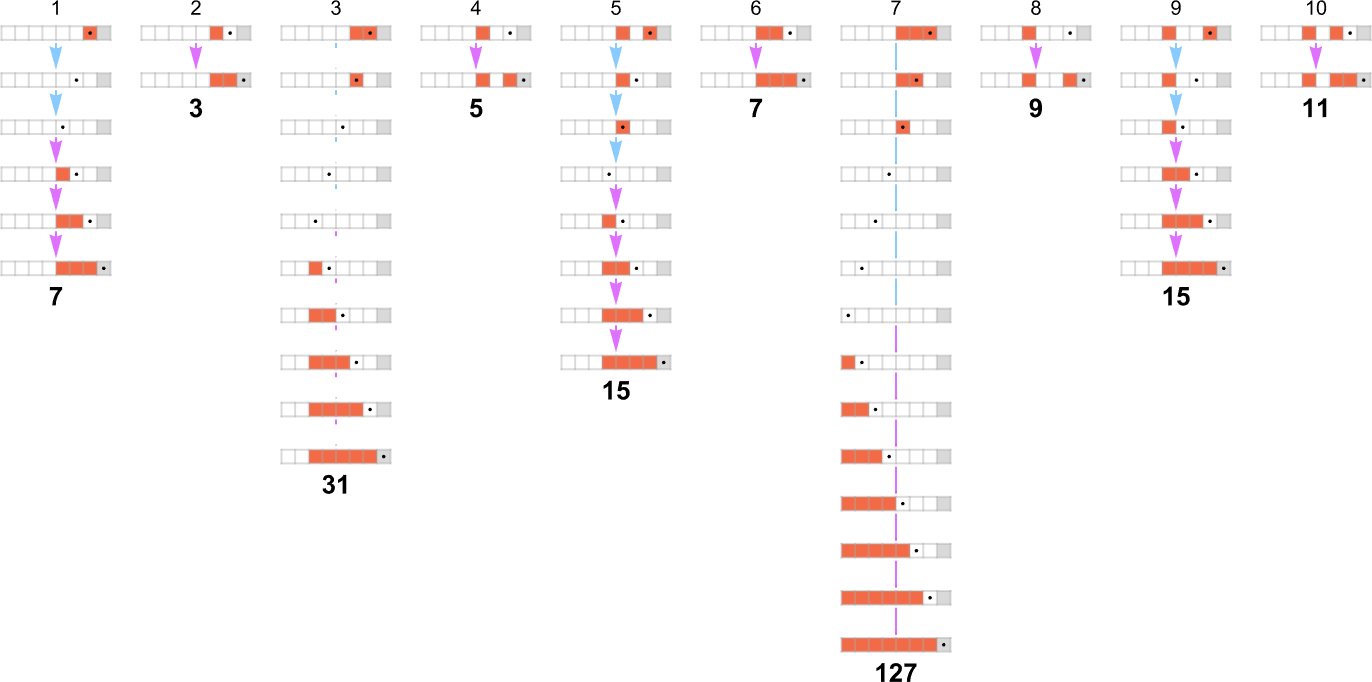

Here’s the actual behavior of these machines when given inputs 1 through 10:

(The lack of runtimes intermediate between quadratic and exponential is notable—and perhaps reminiscent of the rarity of “intermediate growth” seen for example in the cases of finitely generated groups and multiway systems.)

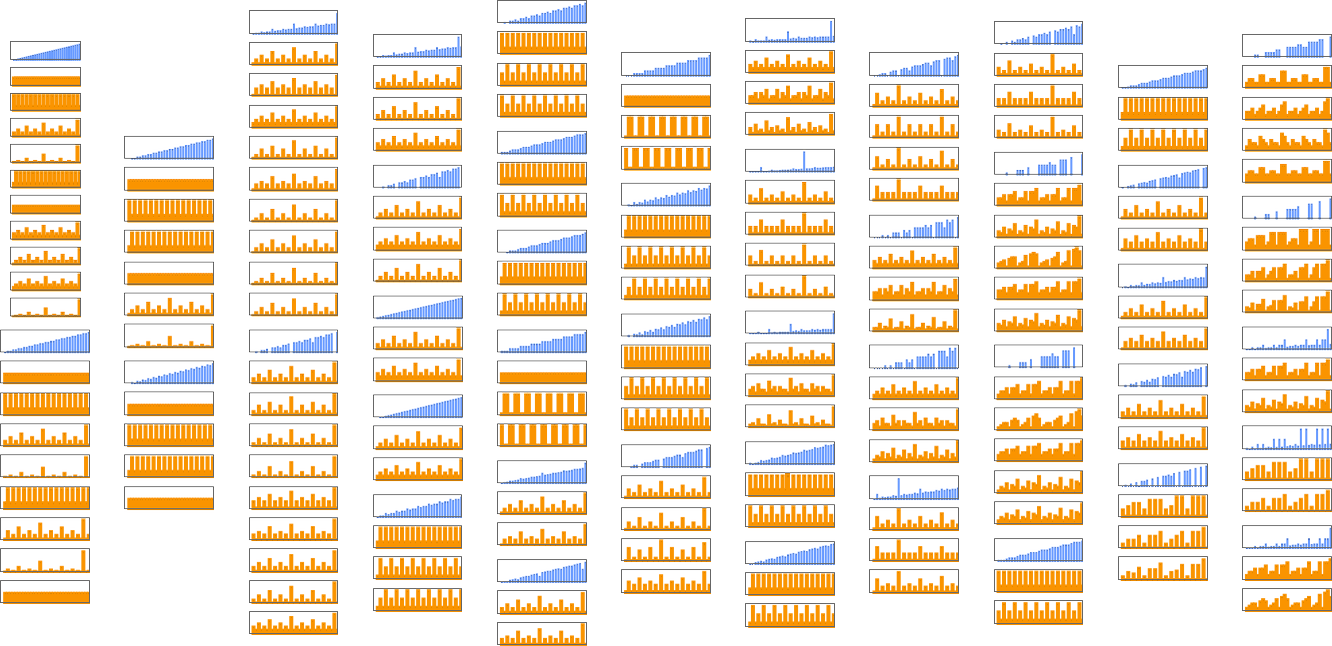

Runtime Distributions

Our emphasis so far has been on worst-case runtimes: the largest runtimes required for inputs of any given size. But we can also ask about the distribution of runtimes within inputs of a given size.

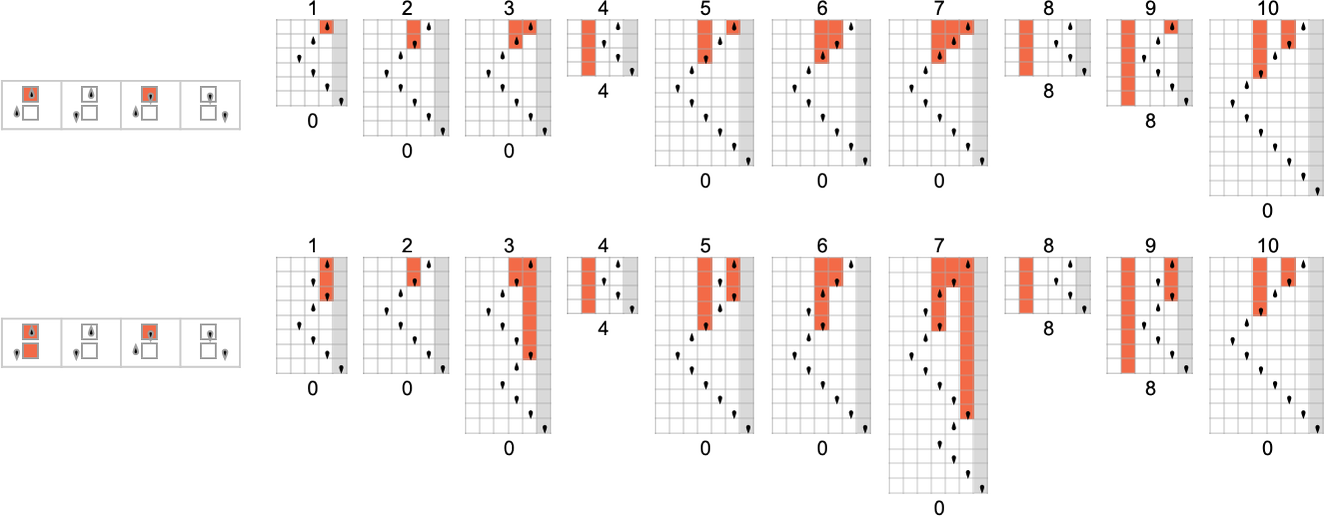

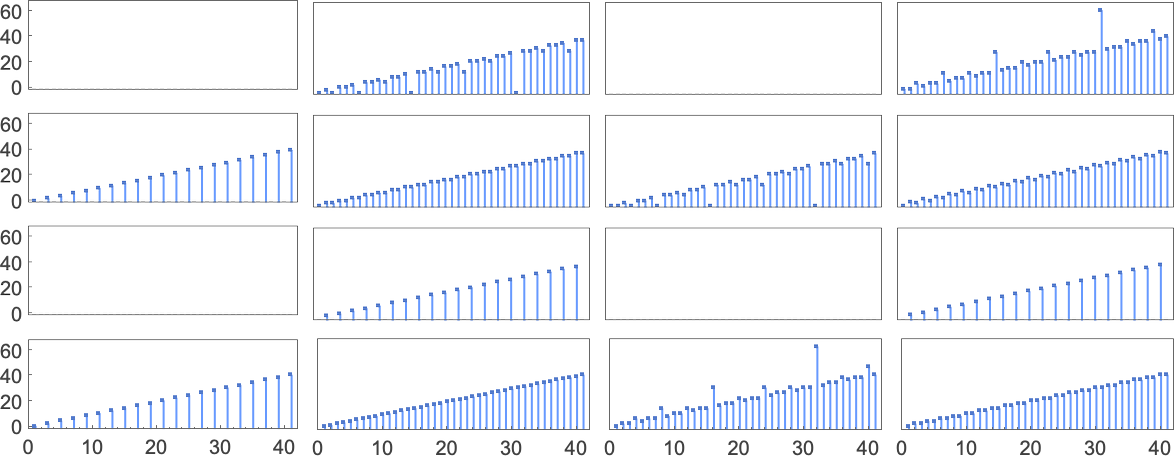

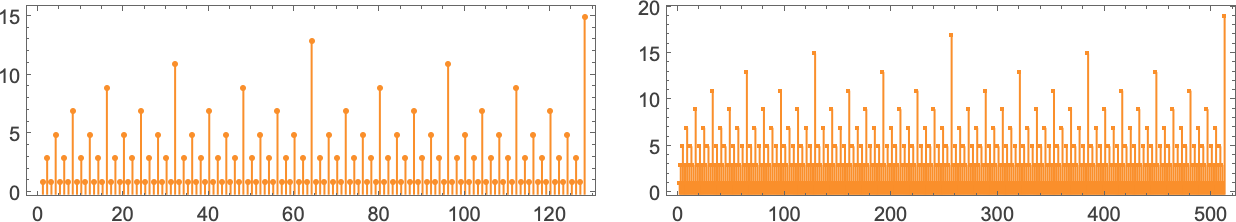

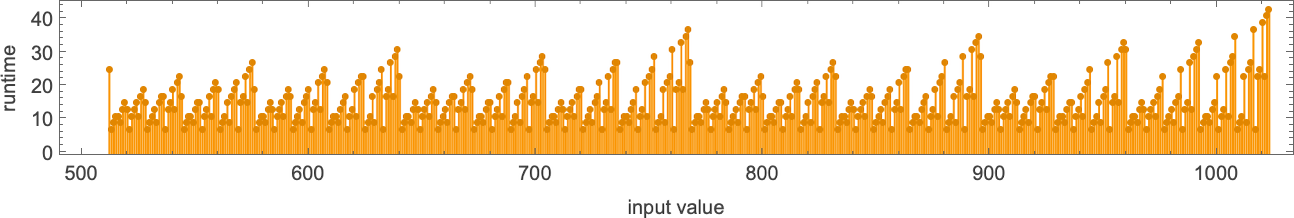

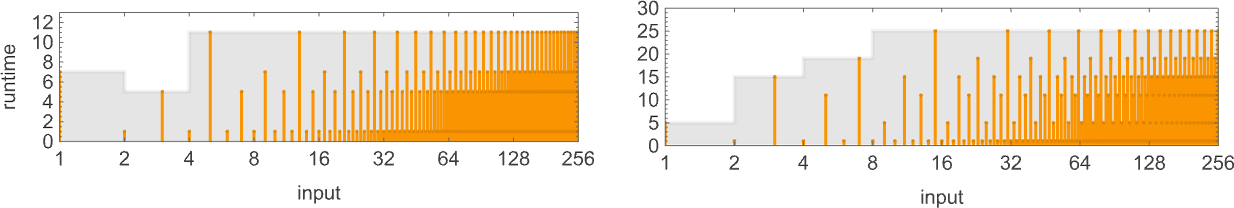

So, for example, here are the runtimes for all size-11 inputs for a particular, fairly typical Turing machine (

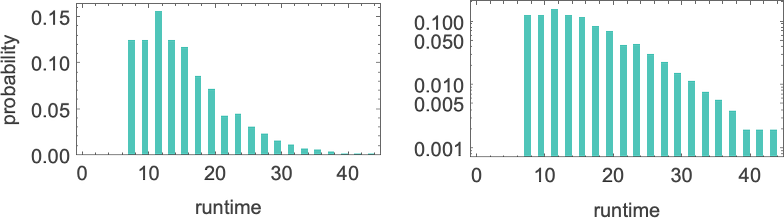

The maximum (“worst-case”) value here is 43—but the median is only 13. In other words, while some computations take a while, most run much faster—so that the runtime distribution is peaked at small values:

(The way our Turing machines are set up, they always run for an even number of steps before terminating—since to terminate, the head must move one position to the right for every position it moved to the left.)

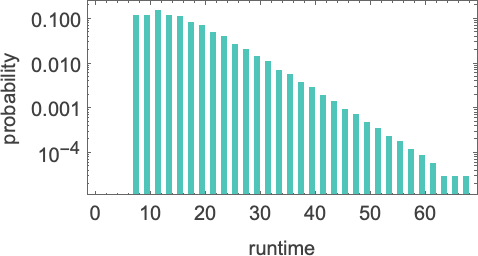

If we increase the size of the inputs, we see that the distribution, at least in this case, is close to exponential:

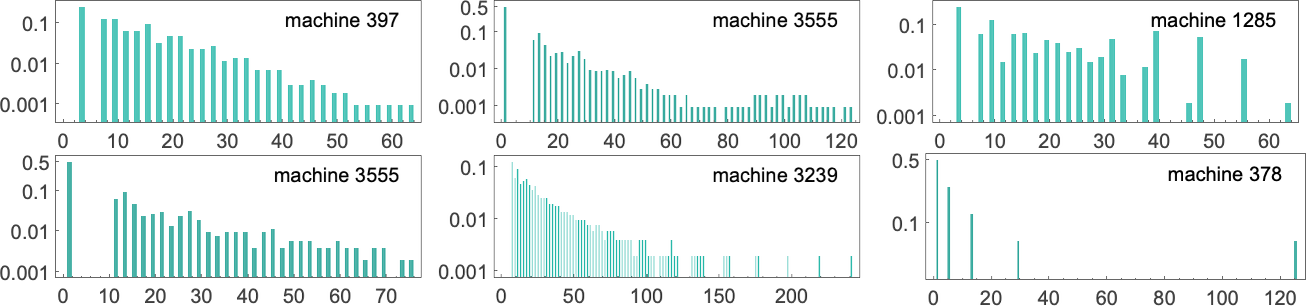

It turns out that this kind of exponential distribution is typical of what we see in almost all Turing machines. (It’s notable that this is rather different from the t –1/2 “stopping time” distribution we’d expect if the Turing machine head was “on average” executing a random walk with an absorbing boundary.) There are nevertheless machines whose distributions deviate significantly from exponential, examples being:

Some simply have long tails to their exponentials. Others, however, have an overall non-exponential form.

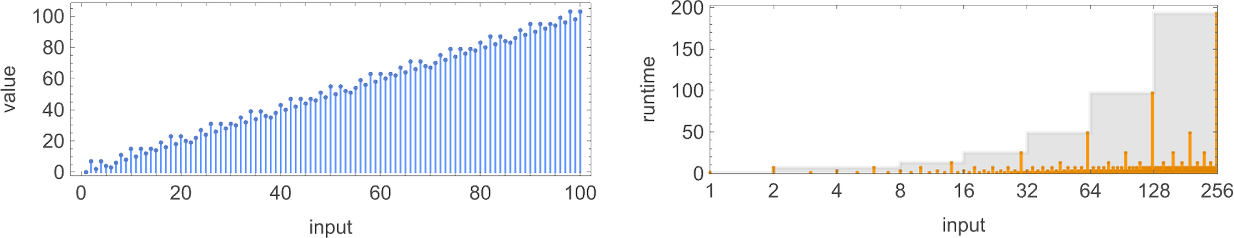

How Fast Can Functions Be Computed?

We’ve now seen lots of functions—and runtime profiles—that

We’ve seen that there are machines that compute functions quite slowly—like in exponential time. But are these machines the fastest that compute those particular functions? It turns out the answer is no.

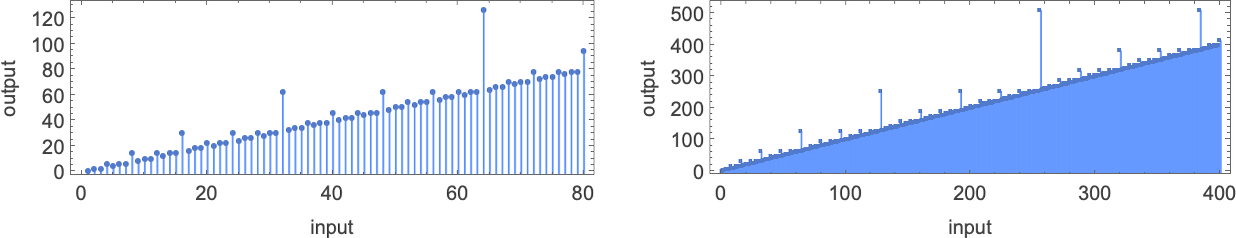

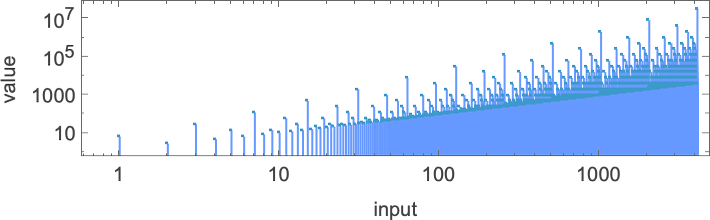

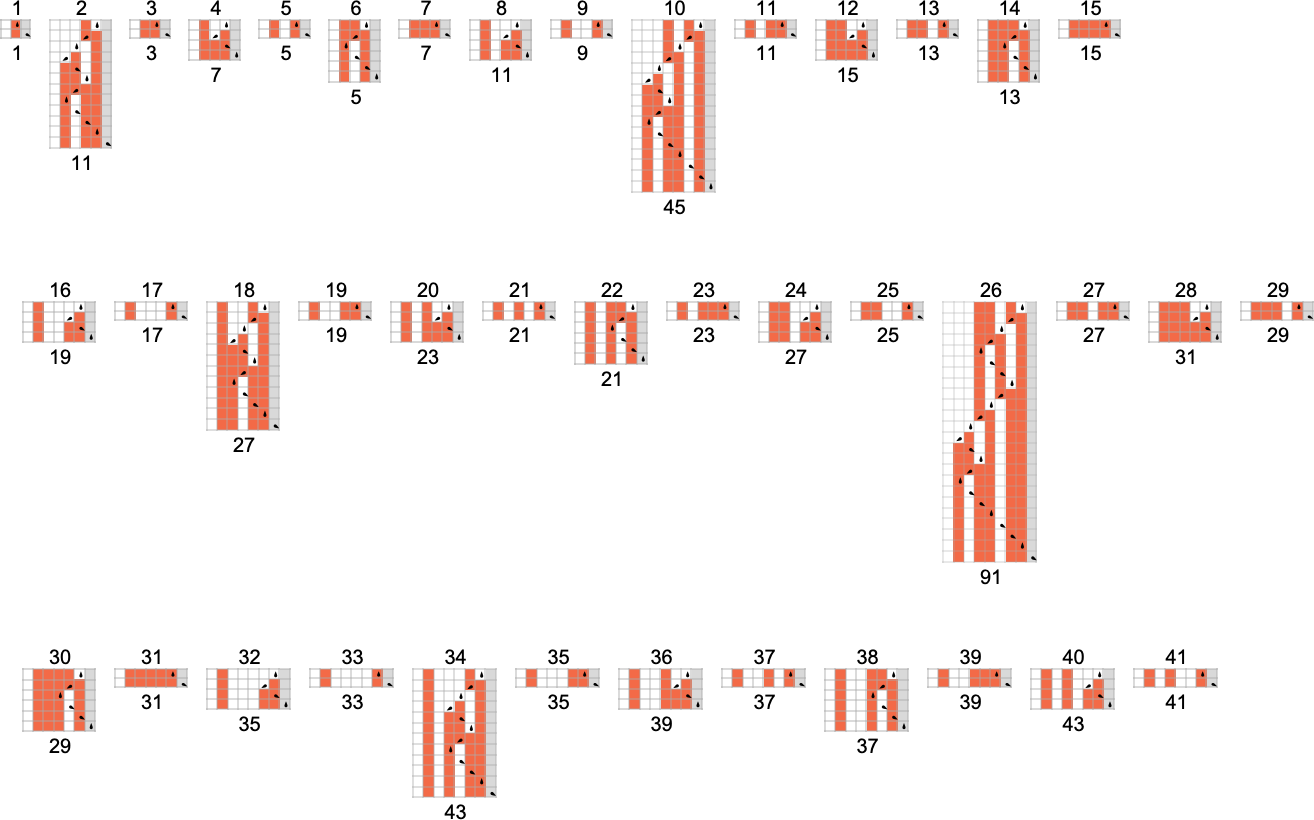

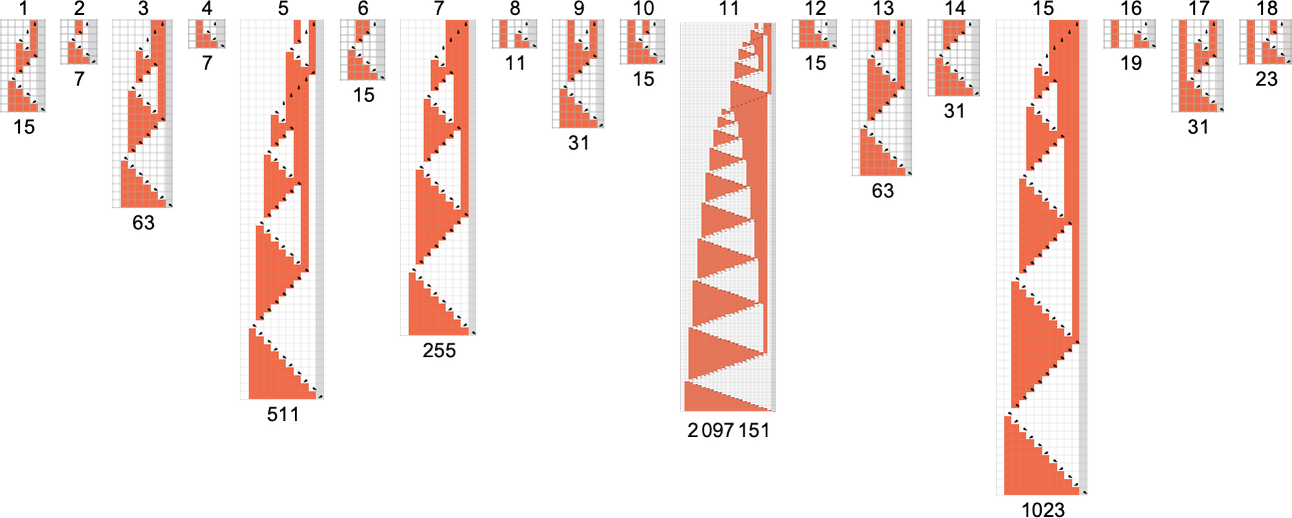

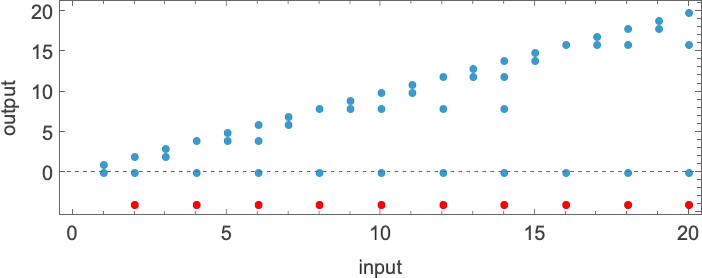

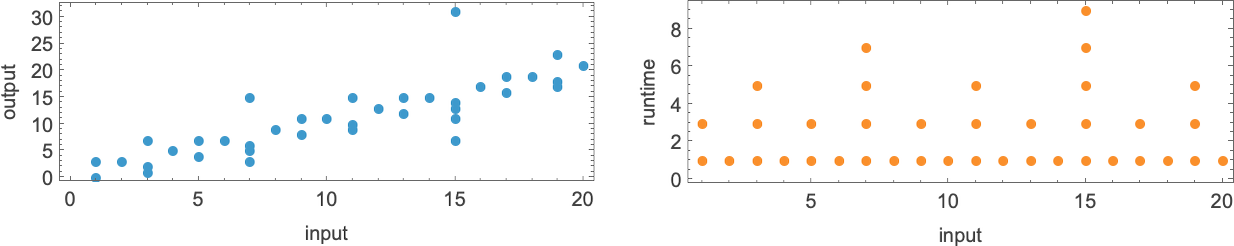

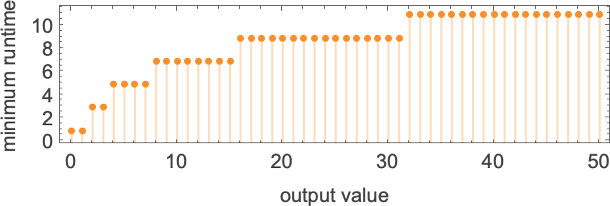

And if we look across all 189 total functions computed by

In other words, there are 8 functions that are the “most difficult to compute” for

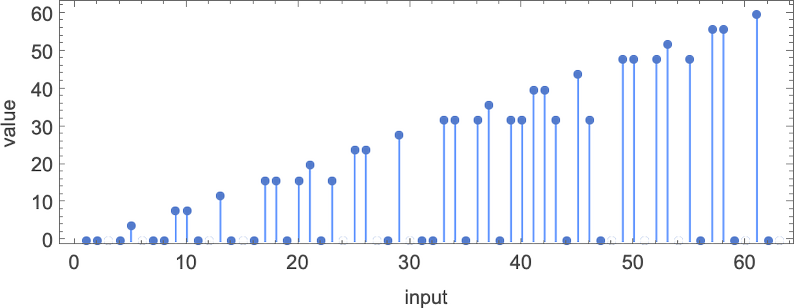

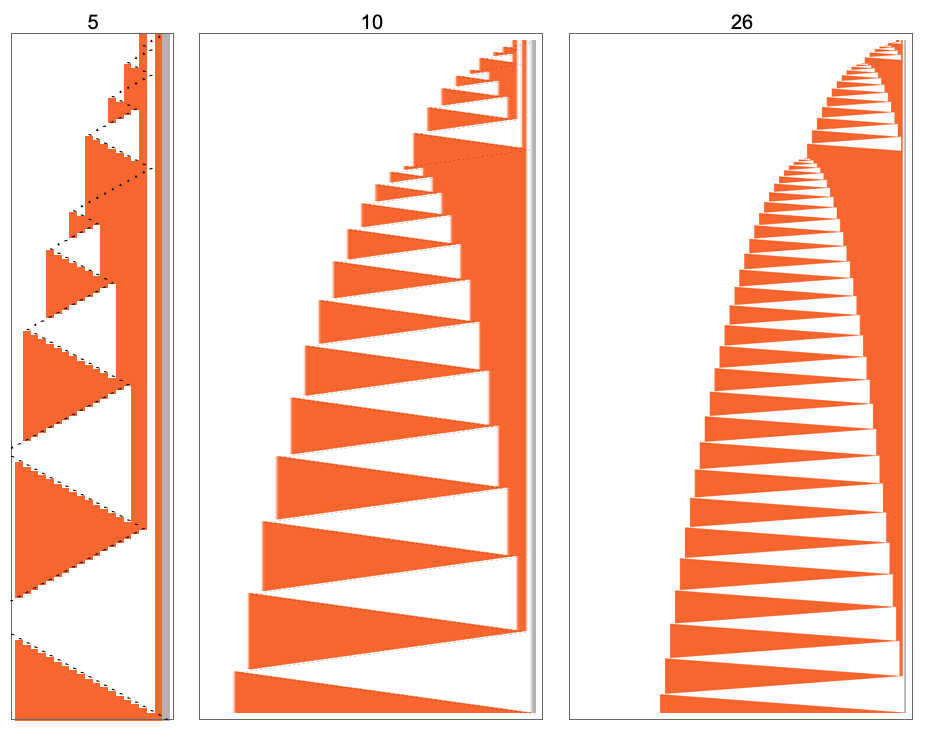

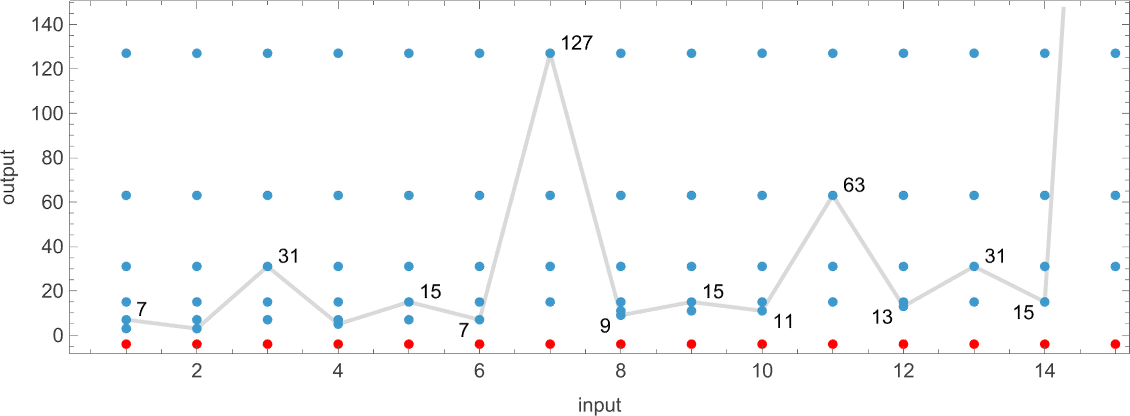

What are these functions? Here’s one of them (computed by machine 1511):

If we plot this function, it seems to have a nested form

which becomes somewhat more obvious on a log-log plot:

As it turns out, there’s what amounts to a “closed form” for this function

though unlike the closed forms we saw above, this one involves Nest, and effectively computes its results recursively:

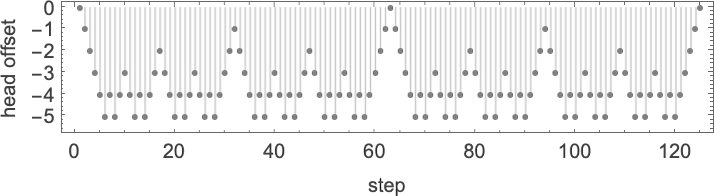

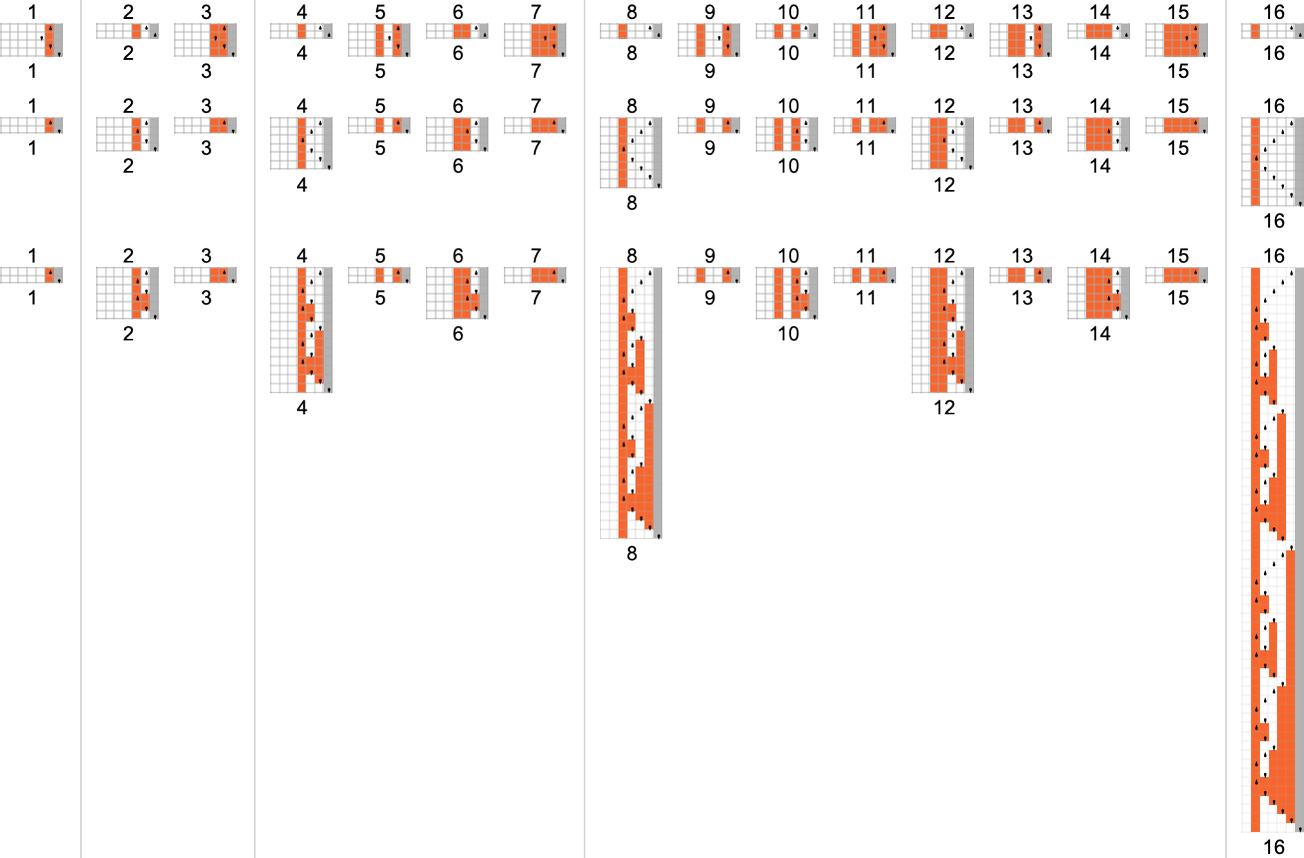

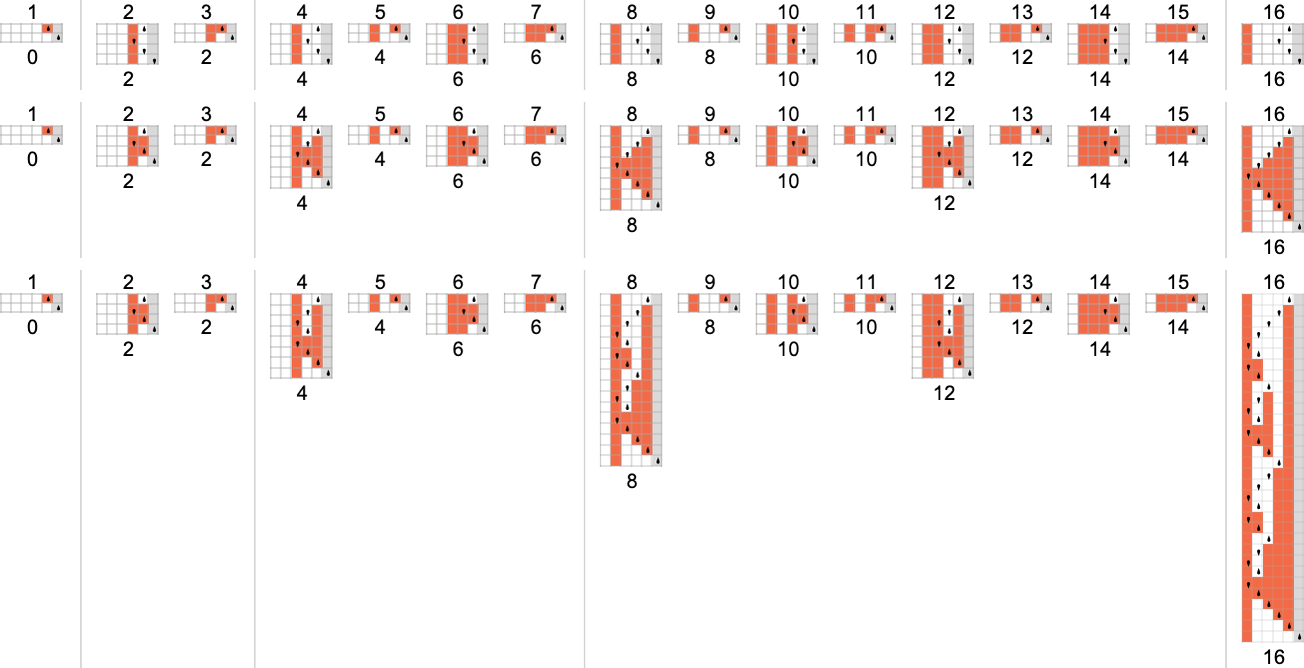

How about machine 1511? Well, here’s how it computes this function—in effect visibly using recursion:

The runtimes are

giving worst-case runtimes for inputs of size n of the form:

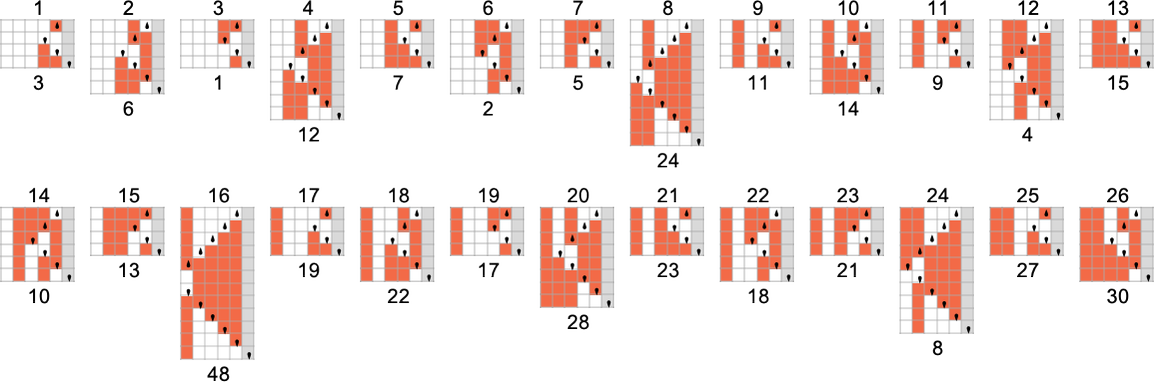

It turns out all 8 functions with minimum runtimes growing like

For the functions with fastest computation times

So what can we conclude? Well, we now know some functions that cannot be computed by

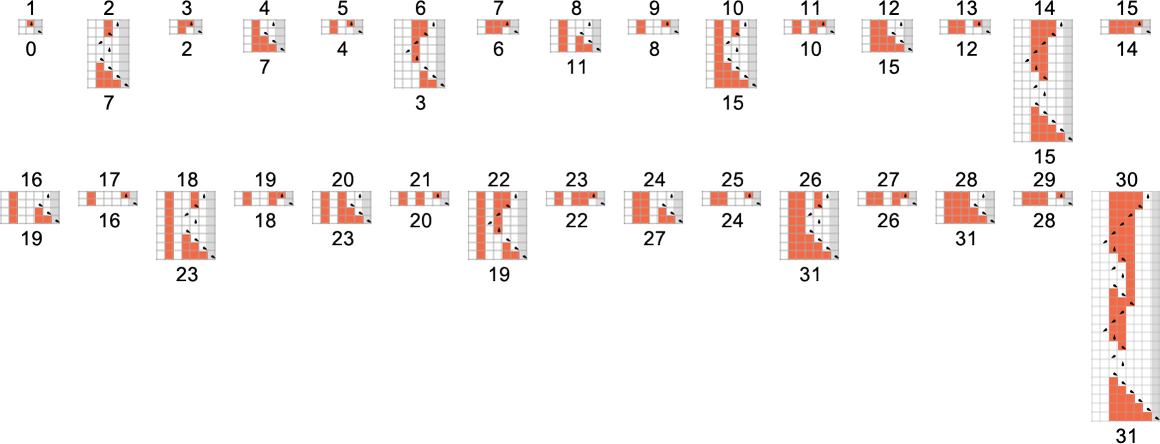

Computing the Same Functions at Different Speeds

We now know the fastest that certain functions can be computed by

And in fact it’s common for there to be only one machine that computes a given function. Out of the 189 total functions that can be computed by

OK, but if multiple machines compute the same function, we can then ask how their speeds compare. Well, it turns out that for 145 of our 189 total functions all the different machines that compute the same function do so with the same “runtime profile” (i.e. with the same runtime for each input i). But that leaves 44 functions for which there are multiple runtime profiles:

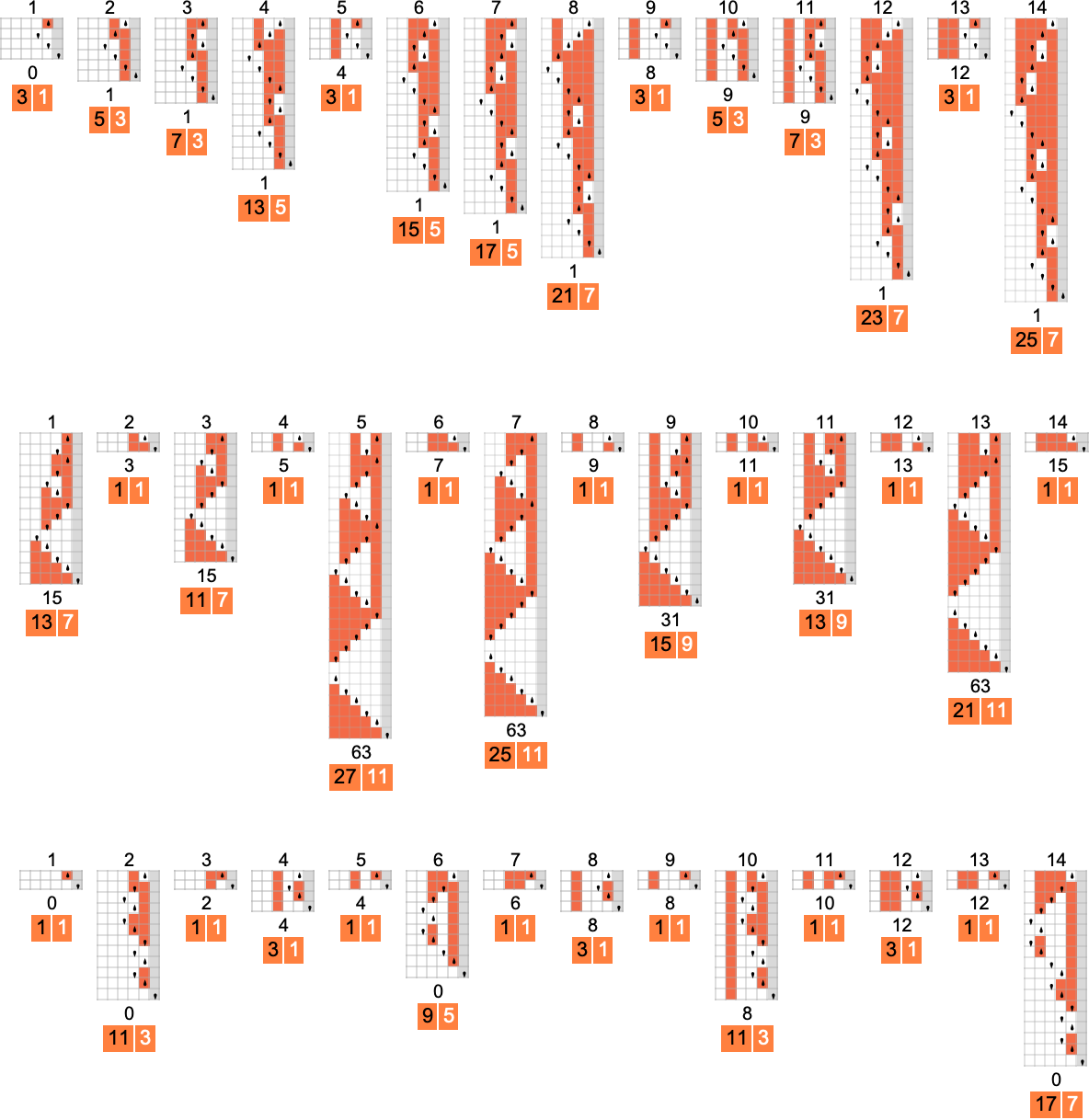

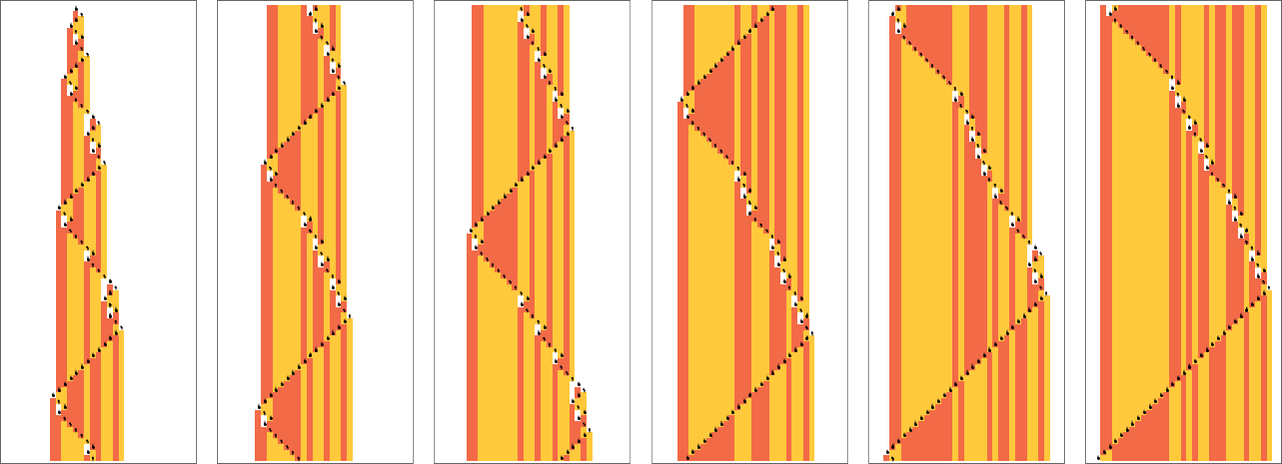

Here are all these 44 functions, together with the distinct runtime profiles for machines that compute them:

Much of the time we see that the possible runtime profiles for computing a given function differ only very little. But sometimes the difference is more significant. For example, for the identity function

Within these 10 profiles, there are 3 distinct rates of growth for the worst-case runtime by input size: constant, linear, and exponential

exemplified by machines 3197, 3589 and 3626 respectively:

Of course, there’s a trivial way to compute this particular function—just by having a Turing machine that doesn’t change its input. And, needless to say, such a machine has runtime 1 for all inputs:

It turns out that for

But although there are not different “orders of growth” for worst-case runtimes among any other (total) functions computed by

by slightly different methods

with different worst-case runtime profiles

or:

By the way, if we consider partial instead of total functions, nothing particularly different happens, at least with

that are again essentially computing the identity function.

Another question is how

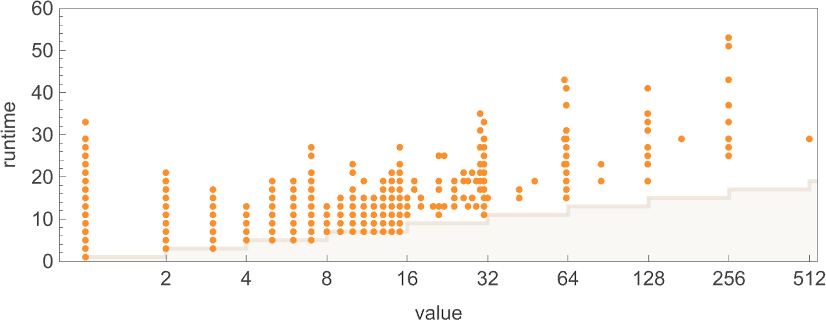

But how fast are the computations? This compares the possible worst-case runtimes for

There must always be ![]() , as in:

, as in:

But can

Absolute Lower Bounds and the Efficiency of Machines

We’ve seen that different Turing machines can take different times to compute particular functions. But how fast can any conceivable Turing machine—even in principle—compute a given function?

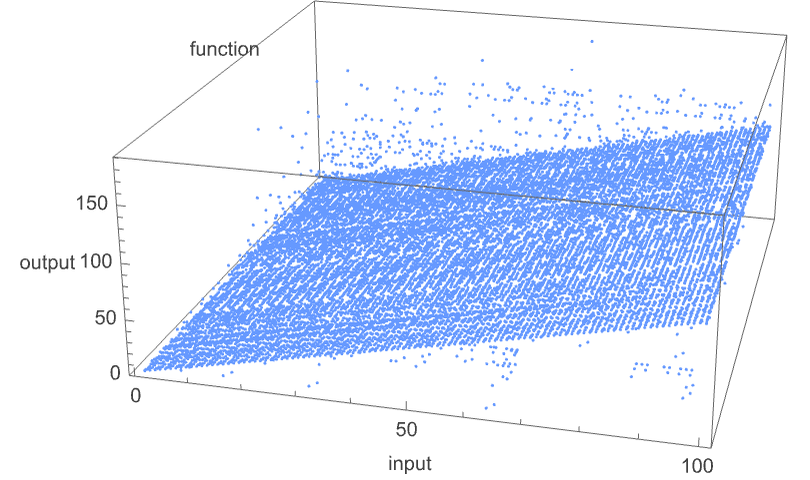

There’s an obvious absolute lower bound to the runtime: with the way we’ve set things up, if a Turing machine is going to take input i and generate output j, its head has to at least be able to go far enough to the left to reach all the bits that need to change in going from i to j—as well as making it back to the right-hand end so that the machine halts. The number of steps required for this is

which for values of i and j up to 8 bits is:

So how do the runtimes of actual Turing machine computations compare with these absolute lower bounds?

Here’s the behavior of s = 1, k = 2 machines 1 and 3, where for each input we’re giving the actual runtime along with the absolute lower bound:

In the second case, the machine is always as efficient as it absolutely can be; in the first case, it only sometimes is—though the maximum slowdown is only 2 steps.

For s = 2, k = 2 machines, the differences can be much larger. For example, machine 378 can take exponential time—even though the absolute lower bound in this case is just 1 step, since this machine computes the identity function:

Here’s another example (machine 1447) in which the actual runtime is always roughly twice the absolute lower bound:

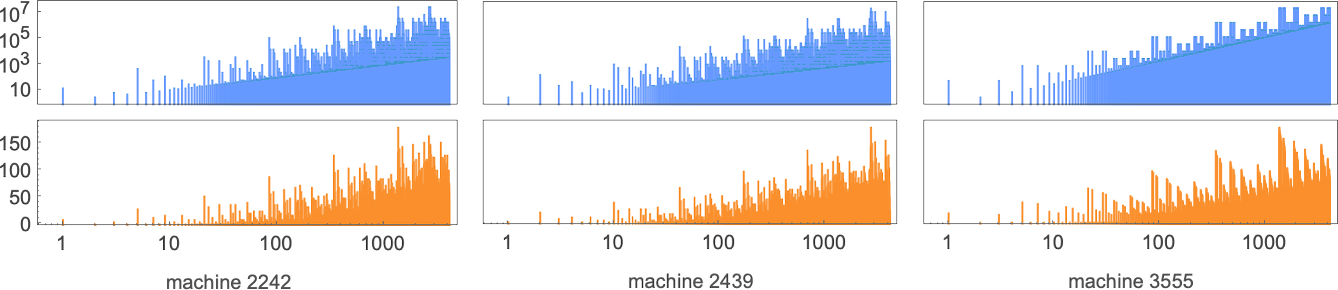

But how does the smallest (worst-case) runtime for any s = 2 Turing machine to compute a given function compare to the absolute lower bound? Well, in a result that presages what we’ll see later in discussing the P vs. NP question, the difference can be increasingly large:

The functions being computed here are

and the fastest s = 2 Turing machines that do this are (machines 2205, 3555 and 2977):

Our absolute lower bound determines how fast a Turing machine can possibly generate a given output. But one can also think of it as something that measures how much a Turing machine has “achieved” when it generates a given output. If the output is exactly the same as the input, the Turing machine has effectively “achieved nothing”. The more they differ, the more one can think of the machine having “achieved”.

So now a question one can ask is: are there functions where little is achieved in the transformation from input to output, but where the minimum runtime to perform this transformation is still long? One might wonder about the identity function—where in effect “nothing is achieved”. And indeed we’ve seen that there are Turing machines that compute this function, but only slowly. However, there are also machines that compute it quickly—so in a sense its computation doesn’t need to be slow.

The function above computed by machine 2205 is a somewhat better example. The (worst-case) “distance” between input and output grows like 2n with the input size n, but the fastest the function can be computed is what machine 2205 does, with a runtime that grows like 10n. Yes, these are still both linear in n. But at least to some extent this is an example of a function that “doesn’t need to be slow to compute”, but is at least somewhat slow to compute—at least for any

Space Complexity

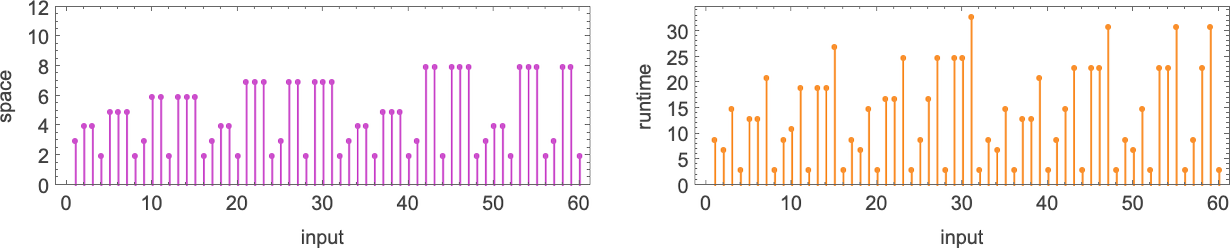

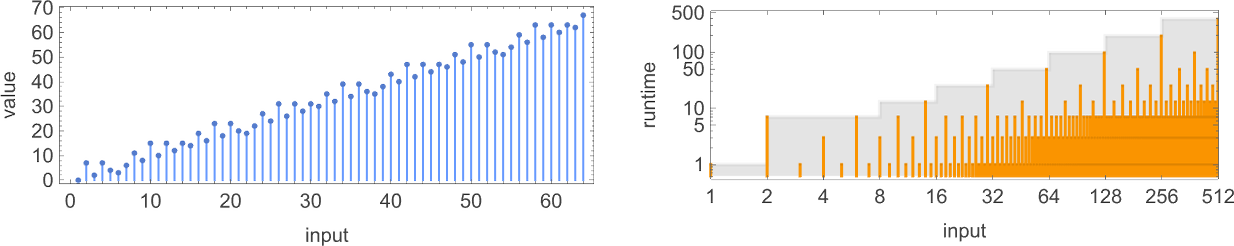

How difficult is it to compute the value of a function, say with a Turing machine? One measure of that is the time it takes, or, more specifically, how many Turing machine steps it takes. But another measure is how much “space” it takes, or, more specifically, with our setup, how far to the left the Turing machine head goes—which determines how much “Turing machine memory” or “tape” has to be present.

Here’s a typical example of the comparison between “space” and “time” used in a particular Turing machine:

If we look at all possible space usage profiles as a function of input size we see that—at least for

(One could also consider different measures of “complexity”—perhaps appropriate for different kinds of idealized hardware. Examples include seeing the total length of path traversed by the head, the total area of the region delimited by the head, the number of times 1 is written to the tape during the computation, etc.)

Runtime Distributions for Particular Inputs across Machines

We’ve talked quite a lot about how runtime varies with input (or input size) for a particular machine. But what about the complementary question: given a particular input, how does runtime vary across different machines? Consider, for example, the

The runtimes for these machines are:

Here’s what we see if we continue to larger inputs:

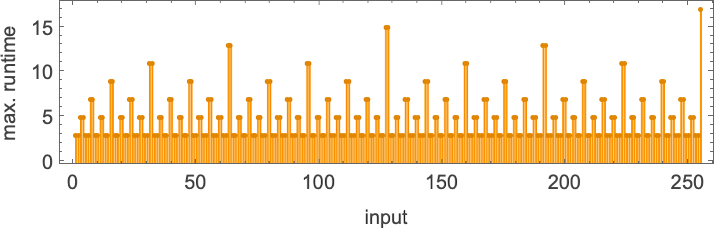

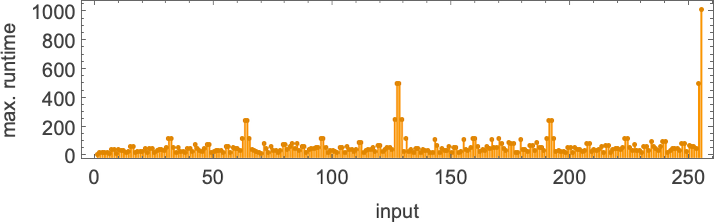

The maximum (finite) runtime across all

or in closed form:

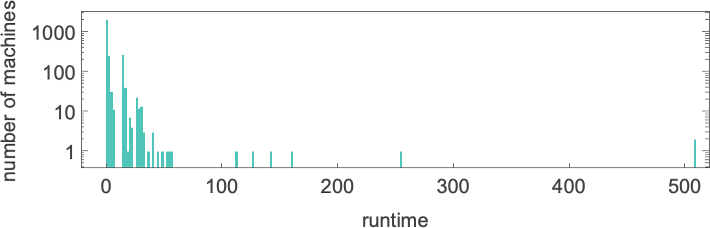

For s = 2, k = 2 machines, the distribution of runtimes with input 1 is

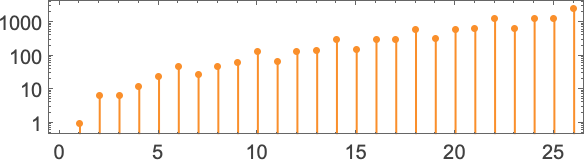

where the maximum value of 17 is achieved for machine 1447. For larger inputs the maximum runtimes are:

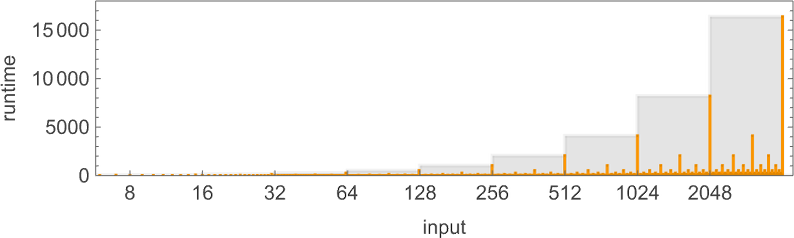

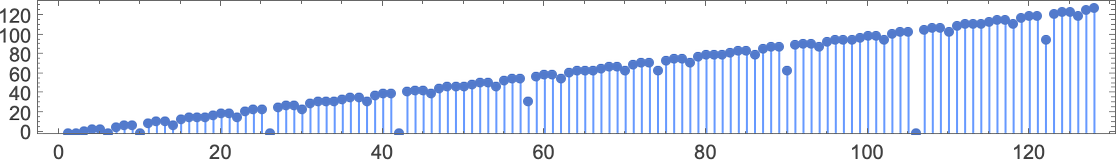

Plotting these maximum runtimes

we see a big peak at input 127, corresponding to runtime 509 (achieved by machines 378 and 1351). And, yes, plotting the distribution for input 127 of runtimes for all machines, we see that this is a significant outlier:

If one computes runtimes maximized over all machines and all inputs for successively larger sizes of inputs, one gets (once again dominated by machines 378 and 1351):

By the way, one can compute not only runtimes but also values and widths maximized across machines:

And, no, the maximum value isn’t always of the form

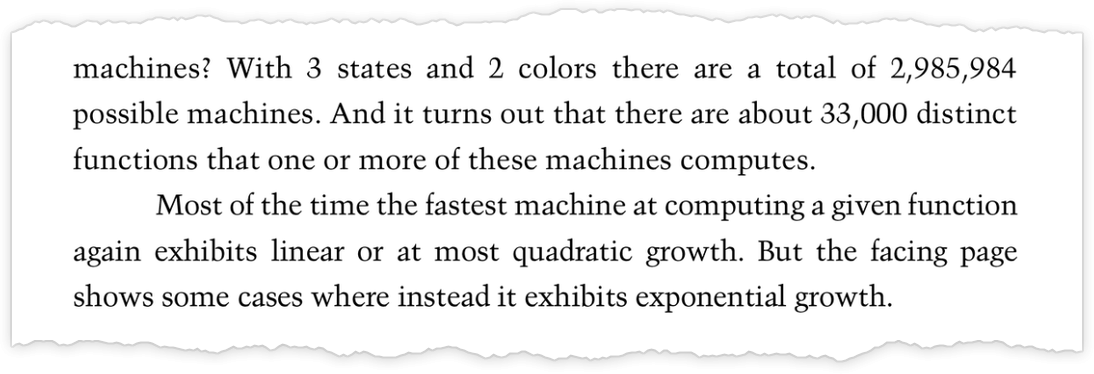

s = 3, k = 2 Turing Machines and the Problem of Undecidability

We’ve so far looked at

The issue—as so often—is of computational irreducibility. Let’s say you have a machine and you’re trying to figure out if it computes a particular function. Or you’re even just trying to figure out if for input i it gives output j. Well, you might say, why not just run the machine? And of course you can do that. But the problem is: how long should you run it for? Let’s say the machine has been running for a million steps, and still hasn’t generated any output. Will the machine eventually stop, producing either output j or some other output? Or will the machine just keep running forever, and never generate any output at all?

If the behavior of the machine was computationally reducible, then you could expect to be able to “jump ahead” and figure out what it would do, without following all the steps. But if it’s computationally irreducible, then you can’t expect to do that. It’s a classic halting problem situation. And you have to conclude that the general problem of determining whether the machine will generate, say, output j is undecidable.

Of course, in lots of particular cases (say, for lots of particular inputs) it may be easy enough to tell what’s going to happen, either just by running for some number of steps, or by using some kind of proof or other abstract derivation. But the point is that—because of computational irreducibility—there’s no upper bound on the amount of computational effort that could be needed. And so the problem of “always getting an answer” has to be considered formally undecidable.

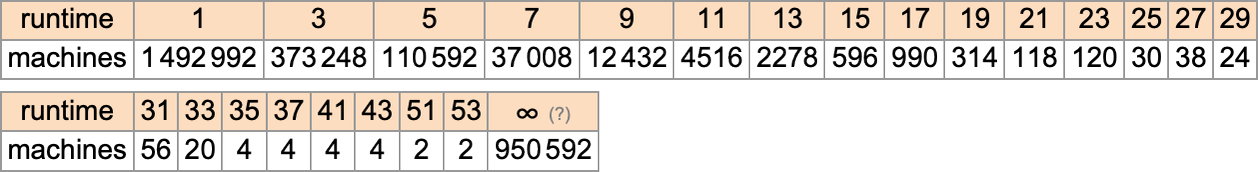

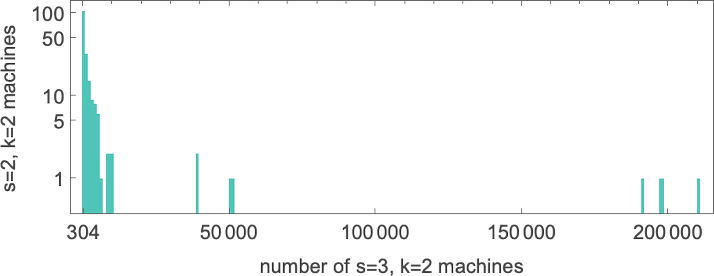

But what happens in practice? Let’s say we look at the behavior of all

And we then conclude that a bit more than half the machines halt—with the largest finite runtime being the fairly modest 53, achieved by machine 630283 (essentially equivalent to 718804):

But is this actually correct? Or do some of the machines we think don’t halt based on running for a million steps actually eventually halt—but only after more steps?

Here are a few examples of what happens:

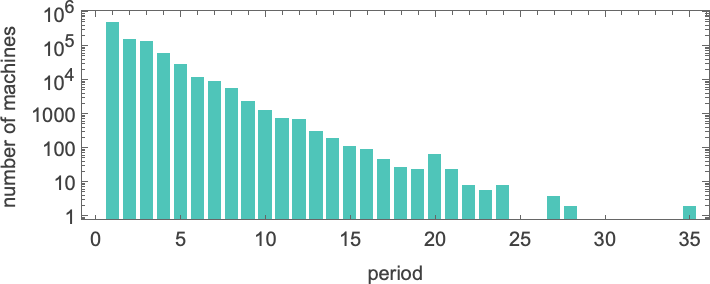

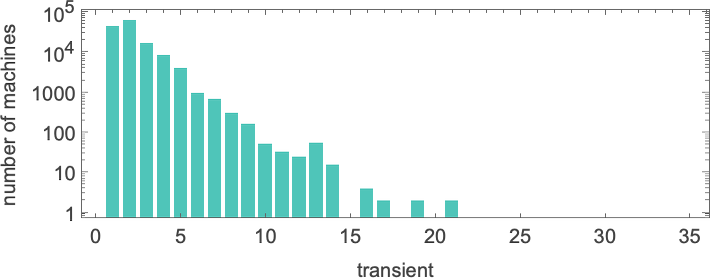

And, yes, in all these cases we can readily see that the machines will never halt—and instead, potentially after some transient, their heads just move essentially periodically forever. Here’s the distribution of periods one finds

with the longest-period cases being:

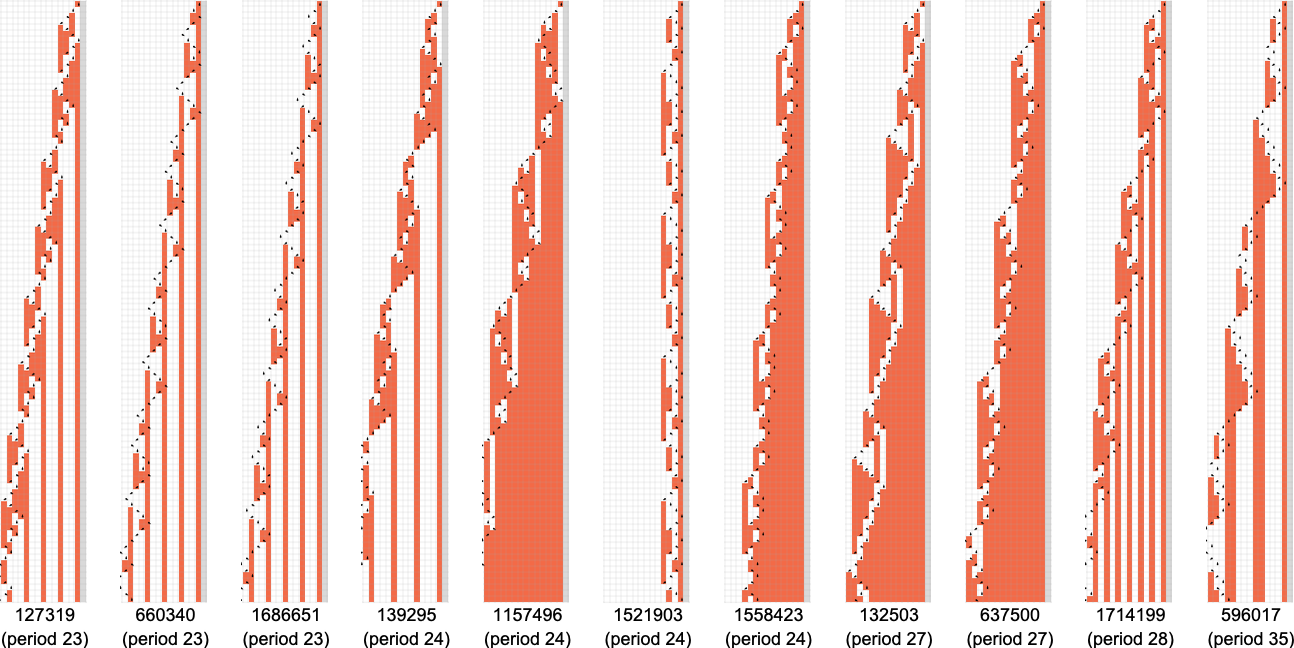

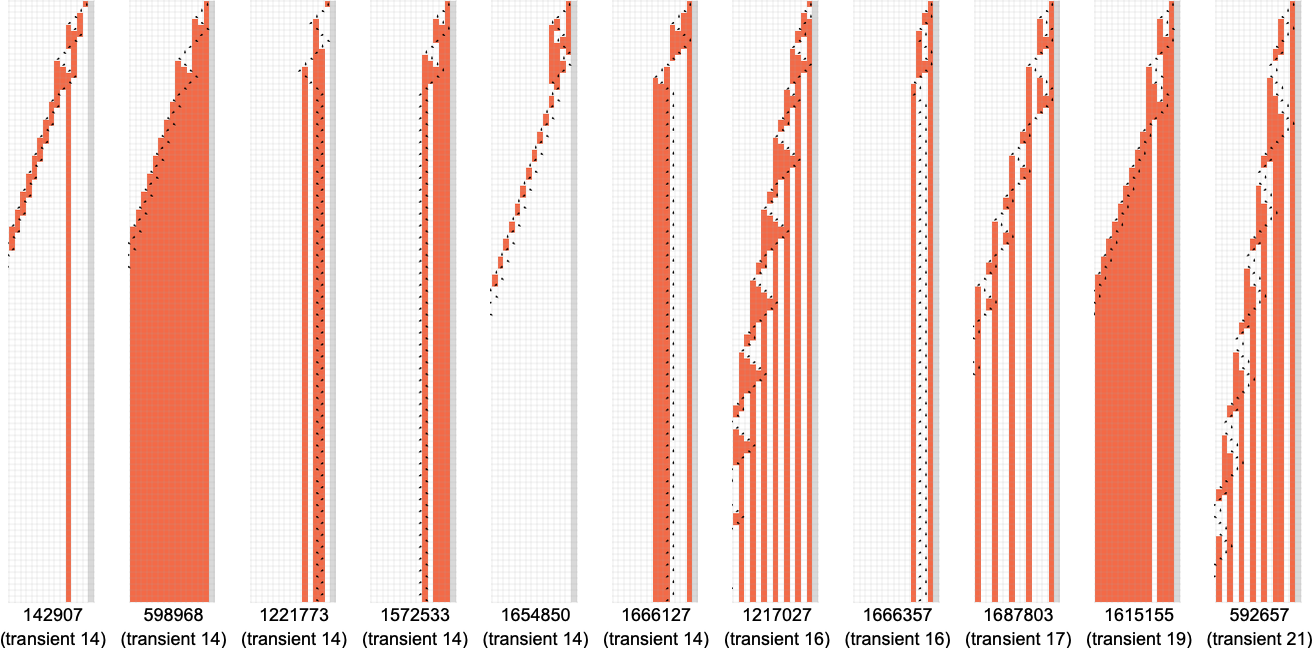

And here’s the distribution of transients

with the longest-transient cases being:

But this doesn’t quite account for all the machines that don’t halt after a million steps: there are still 1938 left over. There are 91 distinct patterns of growth—and here are samples of what happens:

All of these eventually have a fundamentally nested structure. The patterns grow at different rates—but always in a regular succession of steps. Sometimes the spacings between these steps are polynomials, sometimes exponentials—implying either fractional power or logarithmic growth of the corresponding pattern. But the important point for our purposes here is that we can be confident that—at least with input 1—we know which

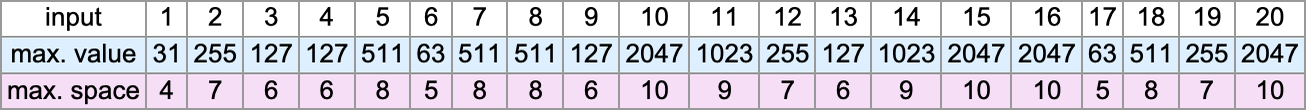

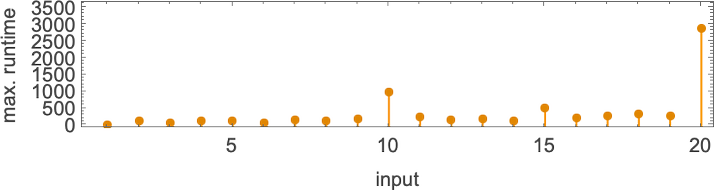

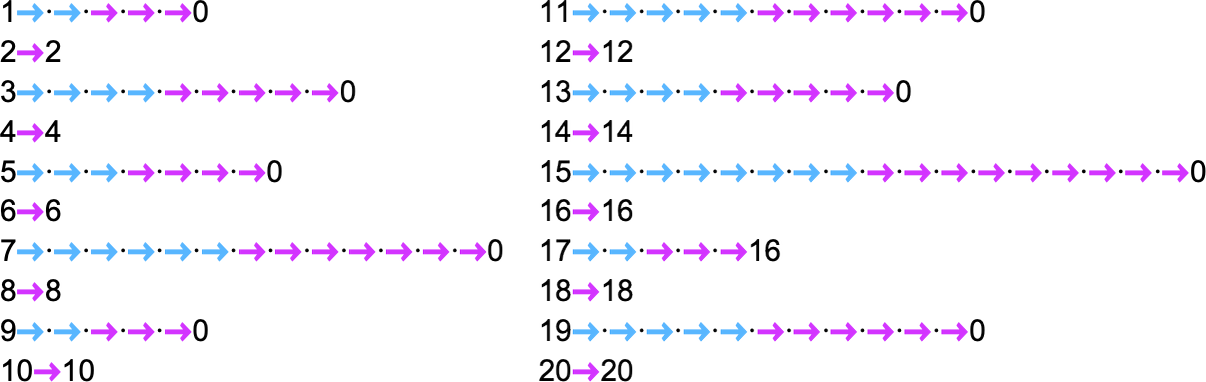

But what happens if we increase the input value we provide? Here are the first 20 maximum finite lifetimes we get:

In the “peak case” of input 10, the distribution of runtimes is

with, yes, the maximum value being a somewhat strange outlier.

What is that outlier? It’s machine 600720 (along with the related machine 670559)—and we’ll be discussing it in more depth in the next section. But suffice it to say now that 600720 shows up repeatedly as the

What about for larger inputs? Well, things get wilder then. Like, for example, consider the case of machine 1955095. For all inputs up to 41, the machine halts after a modest number of steps:

But then, at input 42, there’s suddenly a surprise—and the machine never halts:

And, yes, we can immediately tell it never halts, because we can readily see that the same pattern of growth repeats periodically—every 24 steps. (A more extreme example is

And, yes, things like this are the “long arm” of undecidability reaching in. But by successively investigating both larger inputs and longer runtimes, one can develop reasonable confidence that—at least most of the time—one is correctly identifying both cases that lead to halting, and ones that do not. And from this one can estimate that of all the 2,985,984 possible

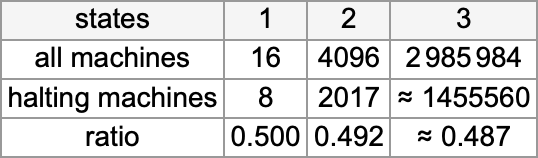

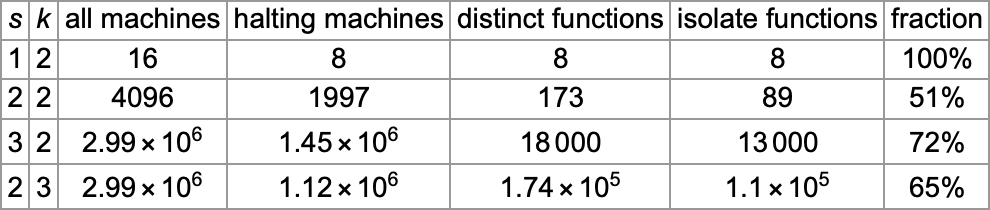

Summarizing our results we find that—somewhat surprisingly—the halting fraction is quite similar for different numbers of states, and always close to 1/2:

And based on our census of halting machines, we can then conclude that the number of distinct total functions computed by

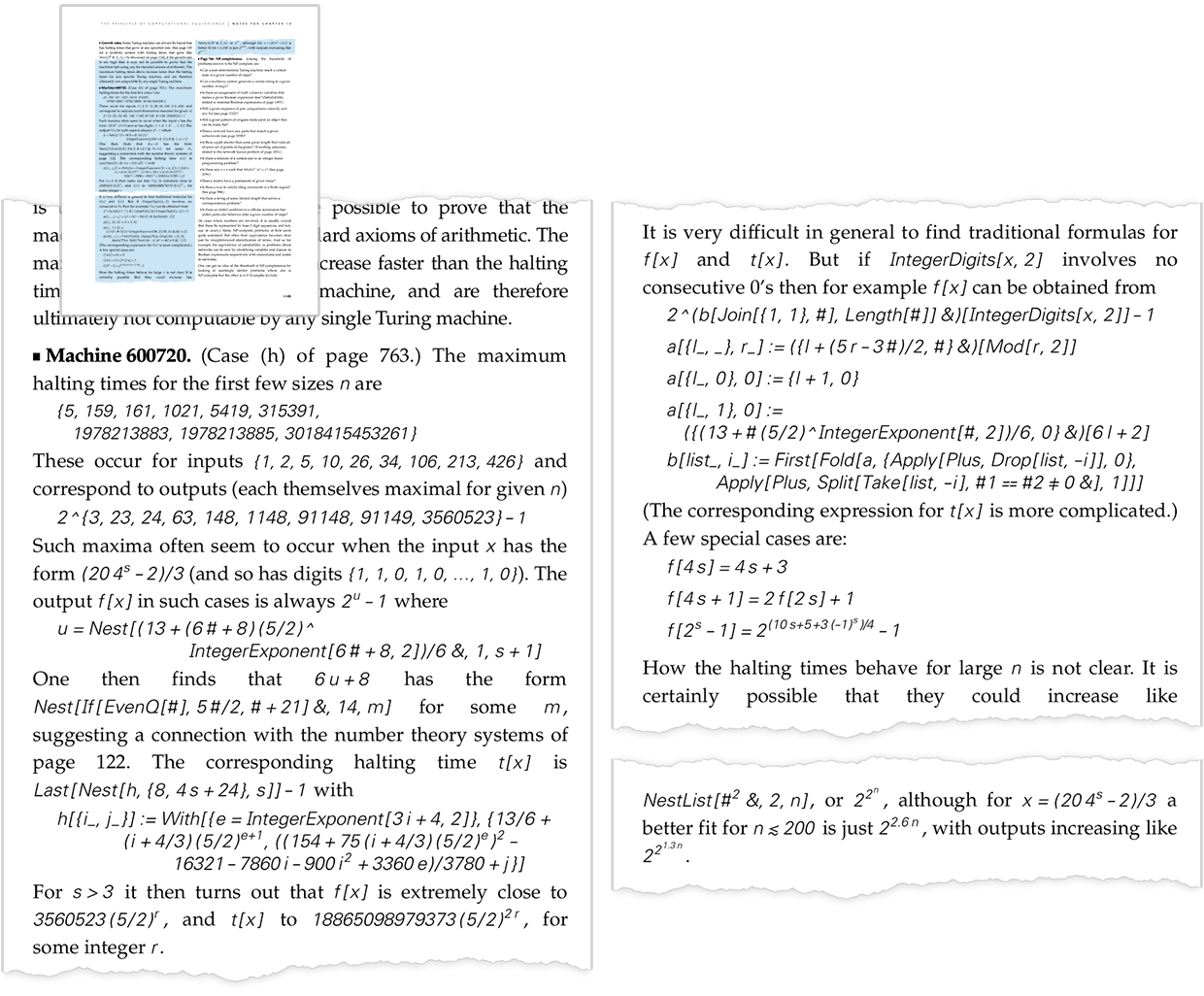

Machine 600720

In looking at the runtimes of

I actually first noticed this machine in the 1990s as part of my work on A New Kind of Science—and with considerable effort was able to give a rather elaborate analysis of at least some of its behavior:

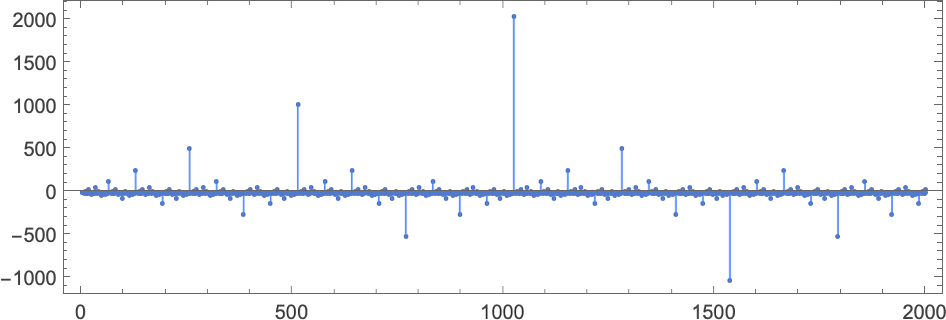

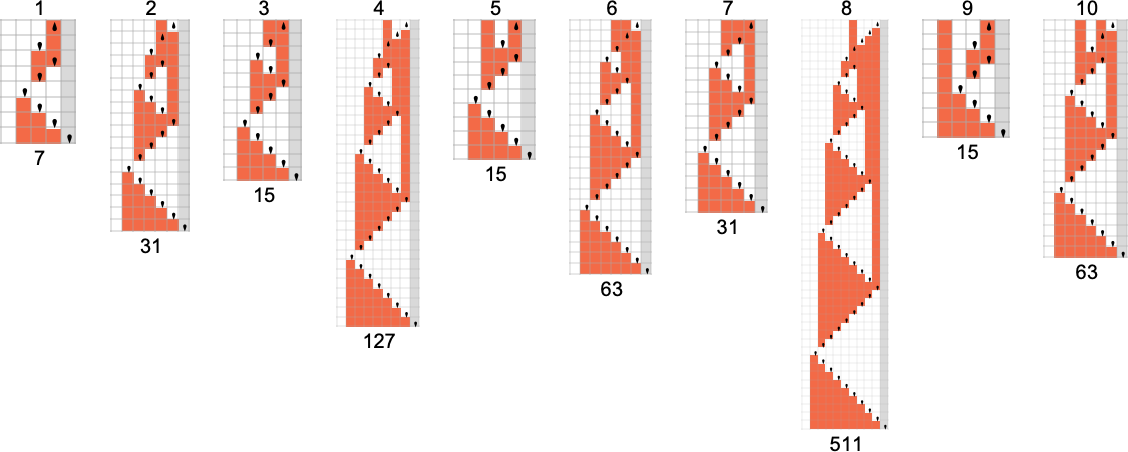

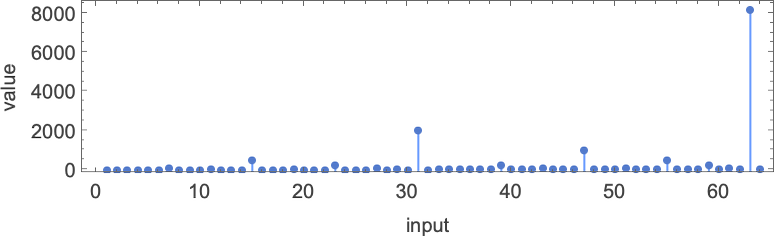

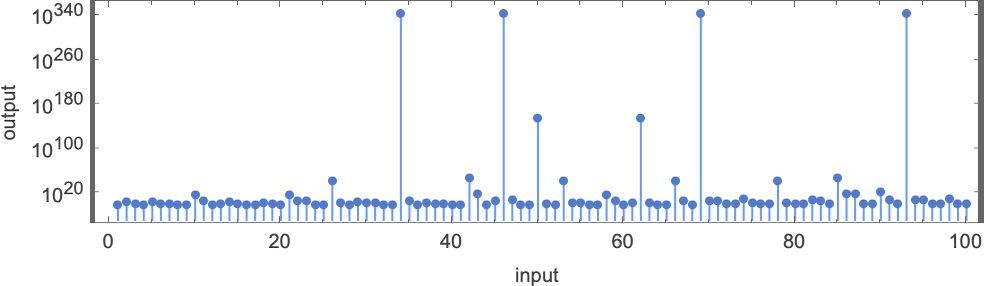

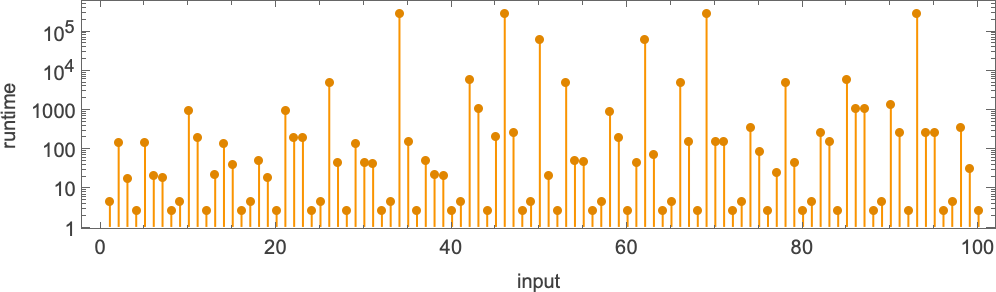

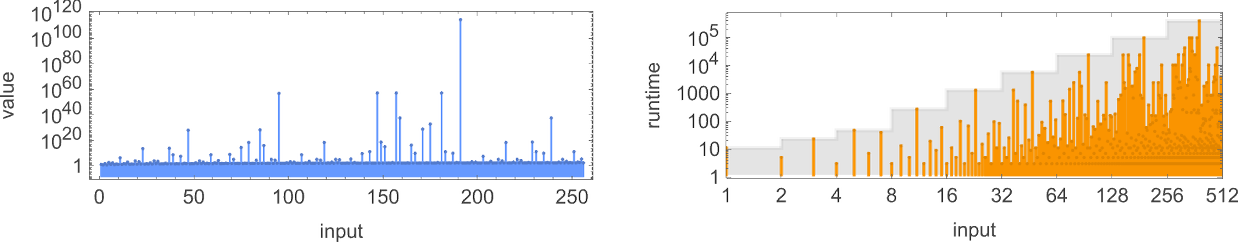

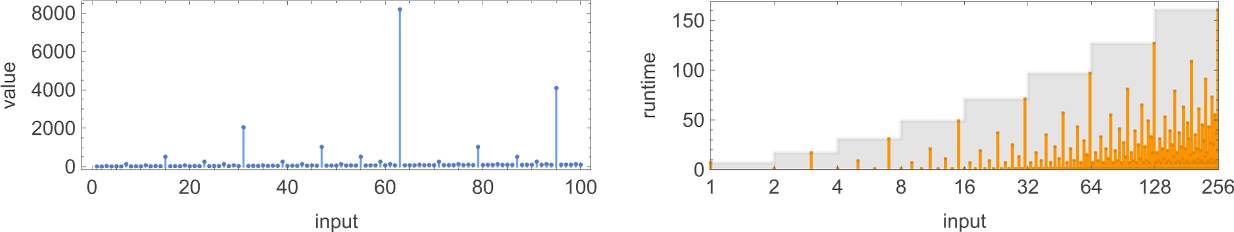

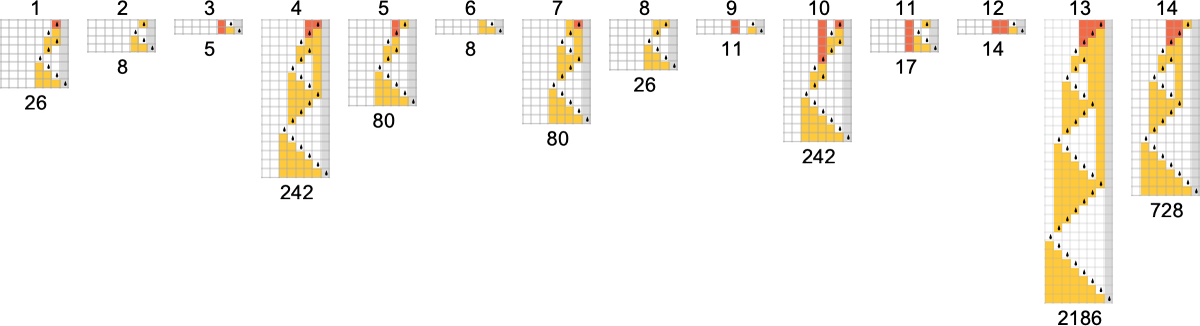

The first remarkable thing about the machine is the dramatic peaks it exhibits in the output values it generates:

These peaks are accompanied by corresponding (somewhat less dramatic) peaks in runtime:

The first of the peaks shown here occurs at input i = 34—with runtime 315,391, and output

but the basic point is that the machine seems to behave in a very “deliberate” way that one might imagine could be analyzed.

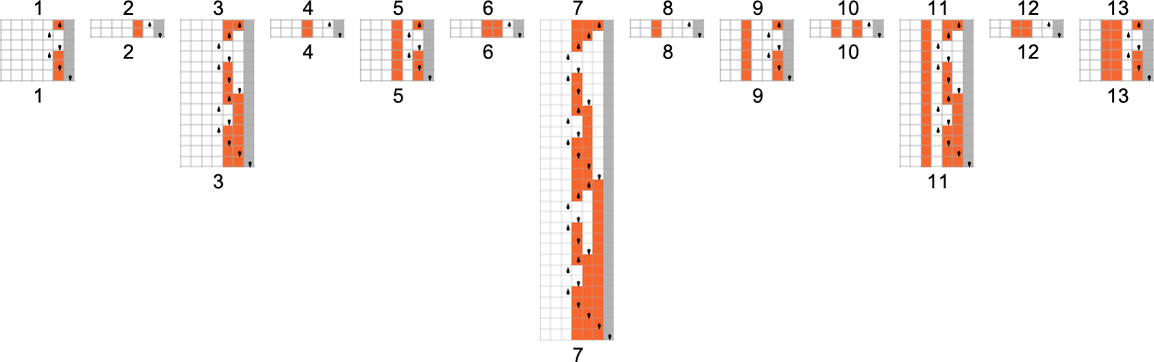

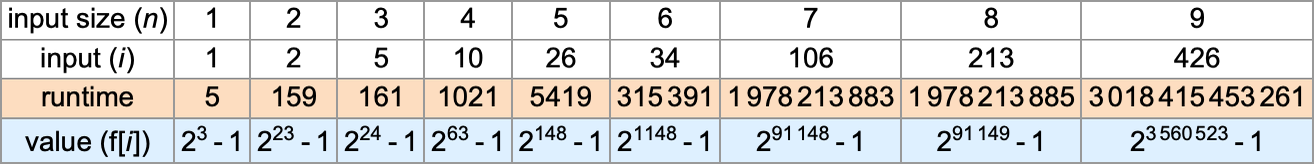

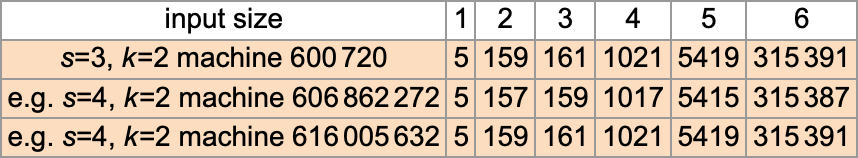

It turns out, though, that the analysis is surprisingly complicated. Here’s a table of maximum (worst-case) runtimes (and corresponding inputs and outputs):

For odd n > 3, the maximum runtime occurs when the input value i is:

The corresponding initial states for the Turing machine are of the form:

The output value with such an input (for odd n > 3) is then

while the runtime—derived effectively by “mathematicizing” what the Turing machine does for these inputs—is given by the bizarrely complex formula:

What is the asymptotic behavior? It’s roughly 6αn where α varies with n according to:

So this is how long it can take the Turing machine to compute its output. But can we find that output faster, say just by finding a “mathematical formula” for it? For inputs i with some particular forms (like the one above) it is indeed possible to find such formulas:

But in the vast majority of cases there doesn’t seem to be any simple mathematical-style formula. And indeed one can expect that this Turing machine is a typical computationally irreducible system: you can always find its output (here the value f[i]) by explicitly running the machine, but there’s no general way to shortcut this, and to systematically get to the answer by some reduced, shorter computation.

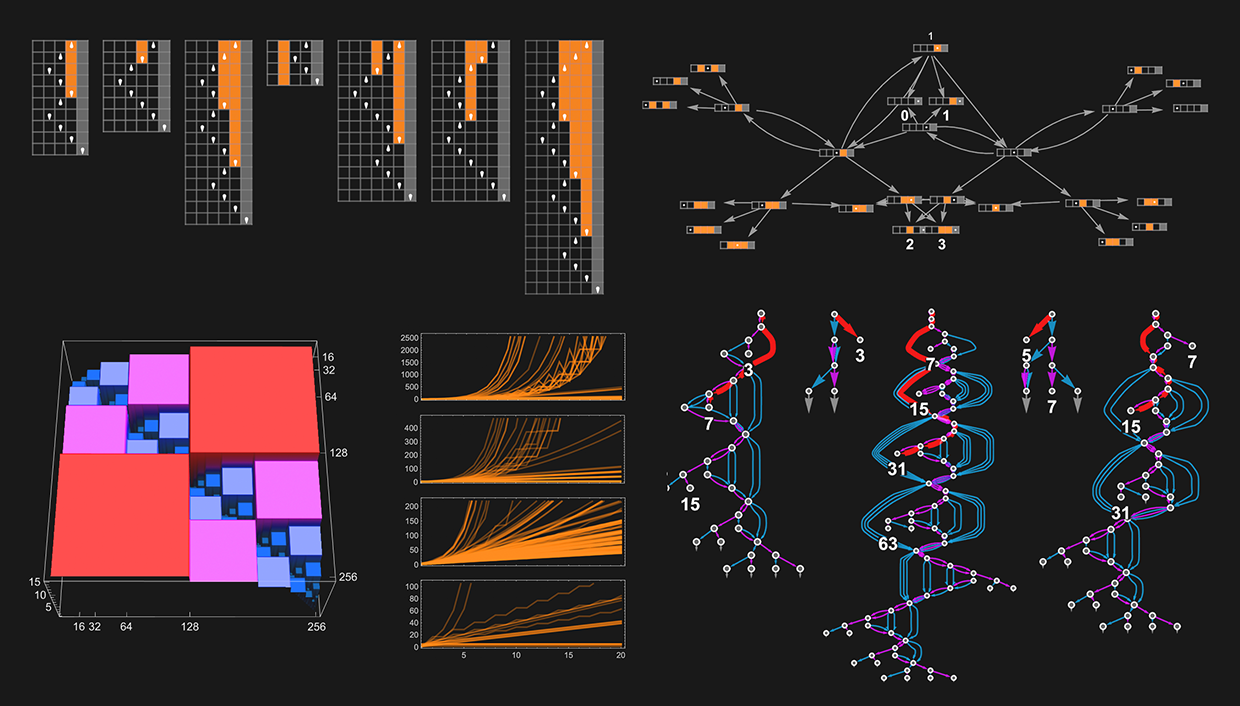

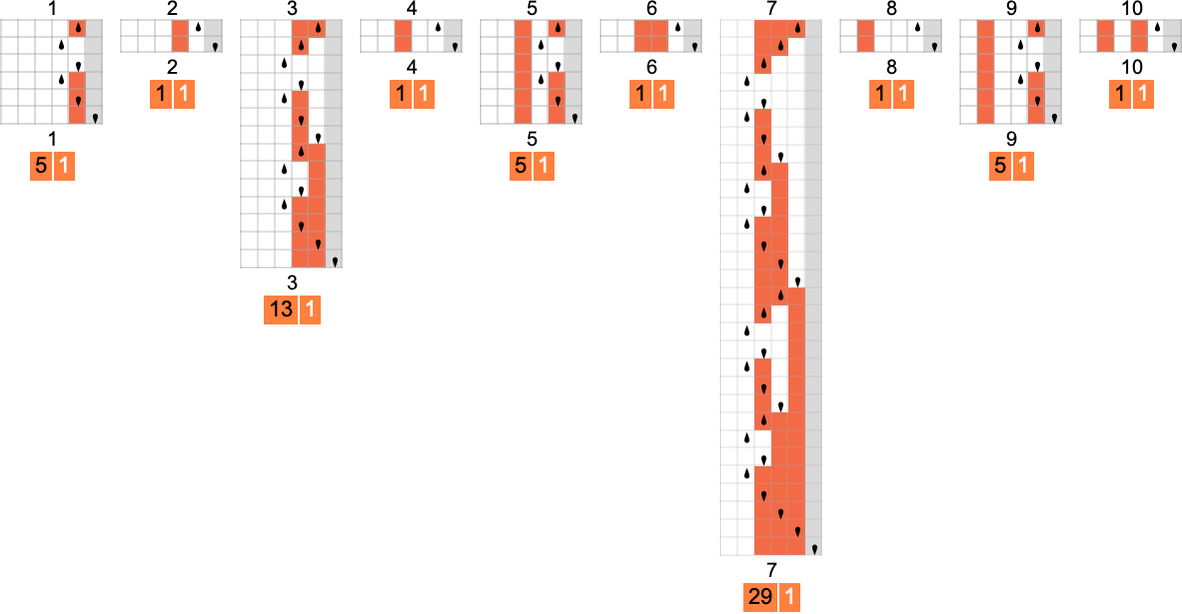

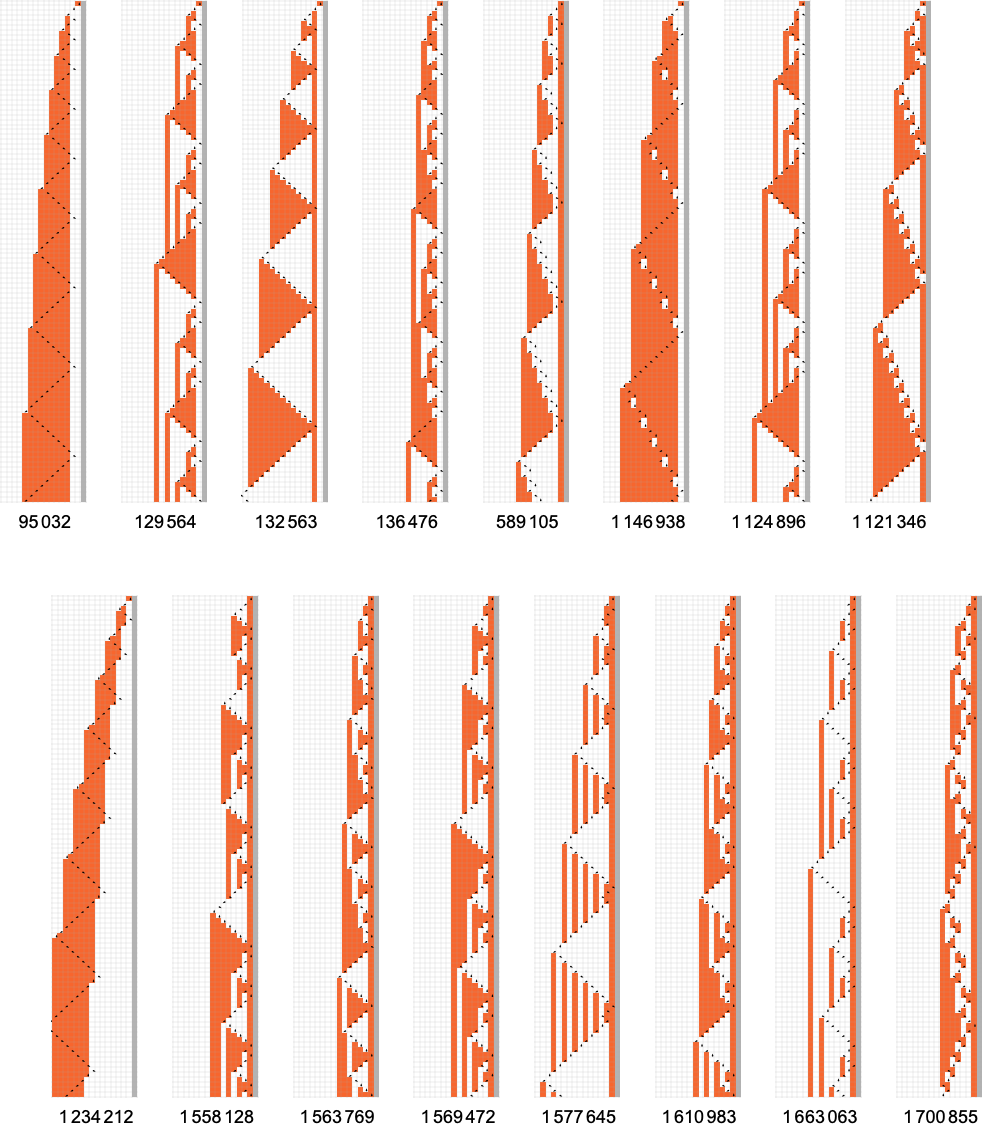

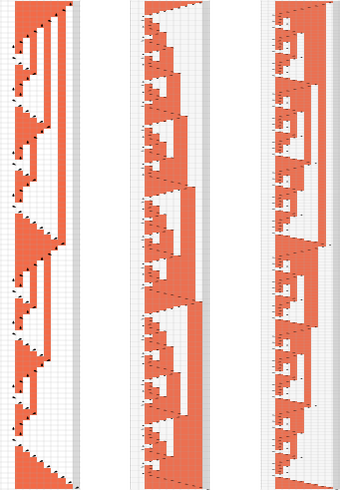

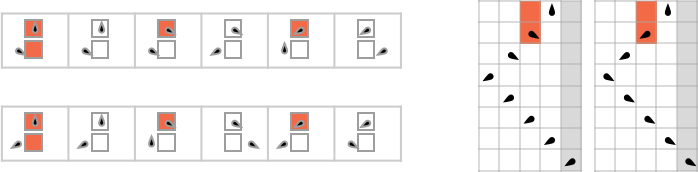

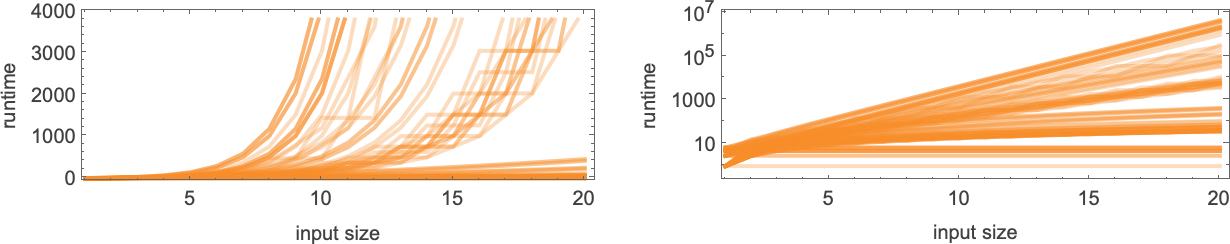

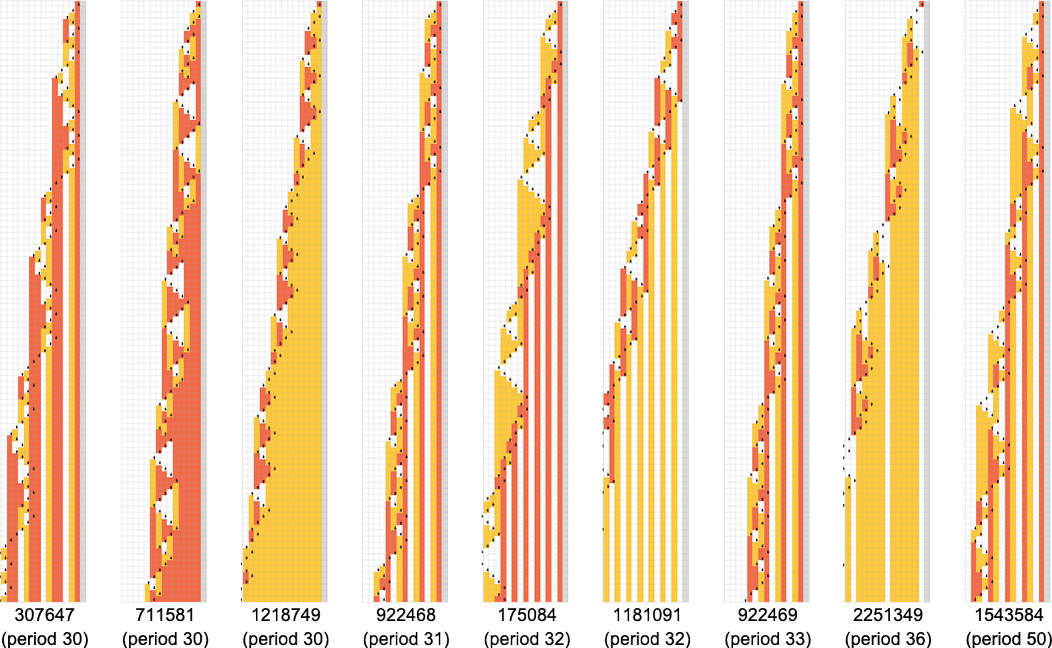

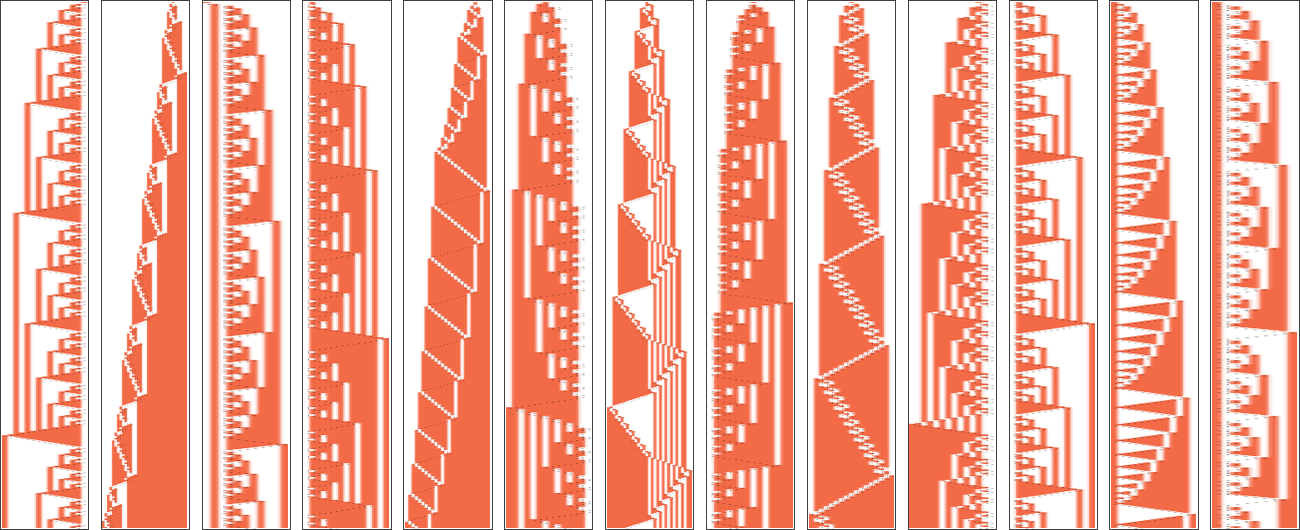

Runtimes in s = 3, k = 2 Turing Machines

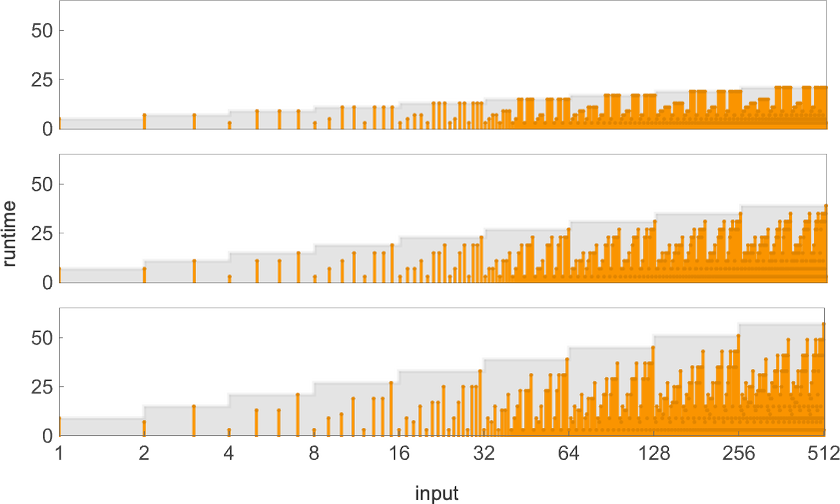

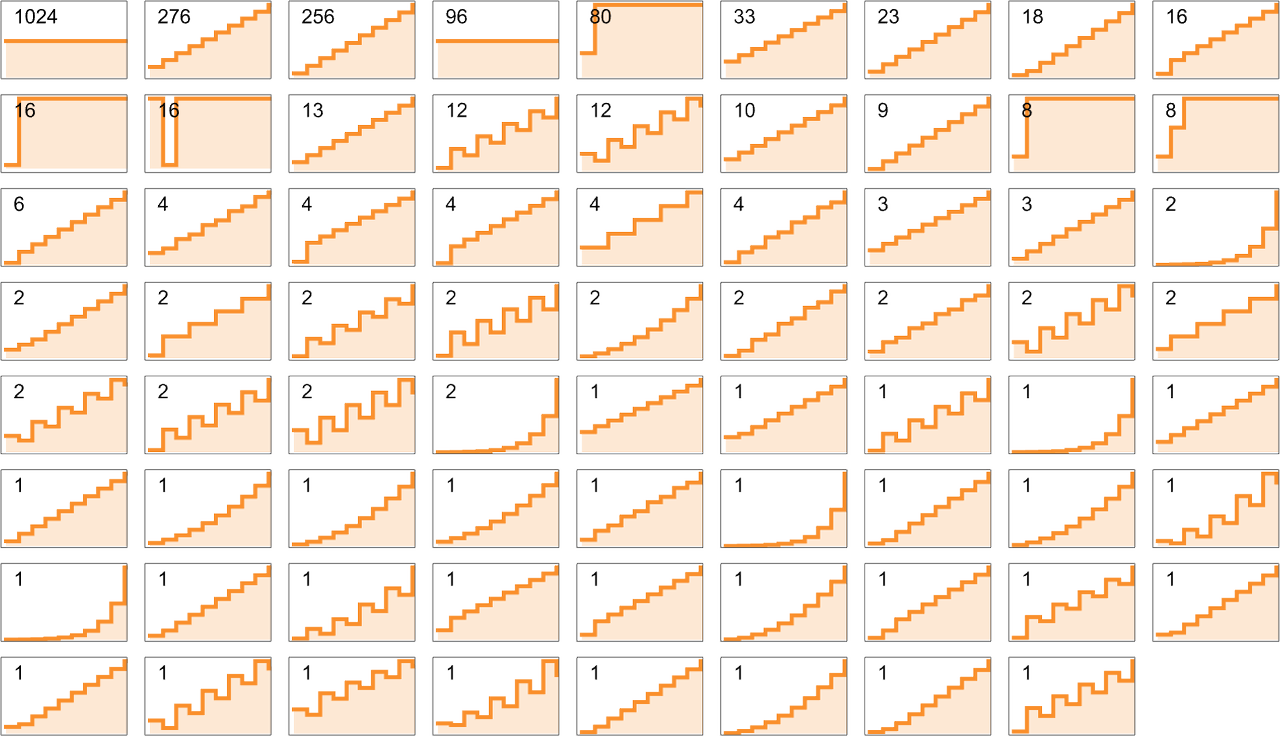

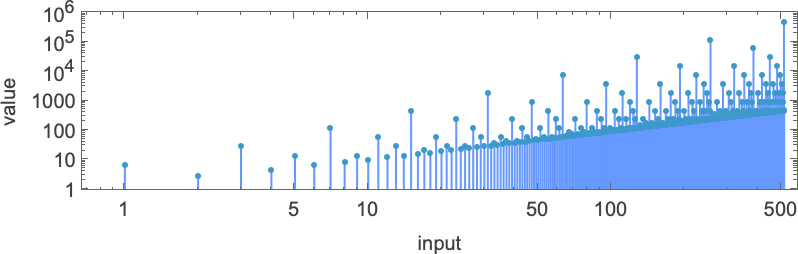

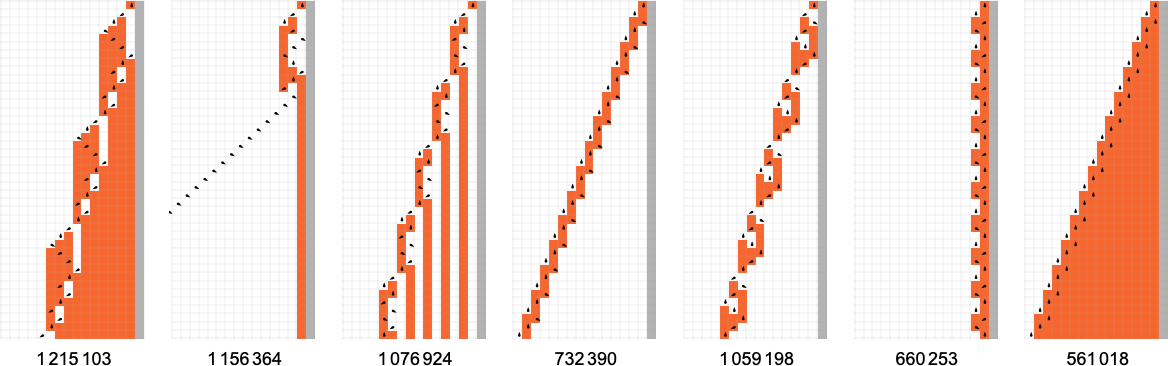

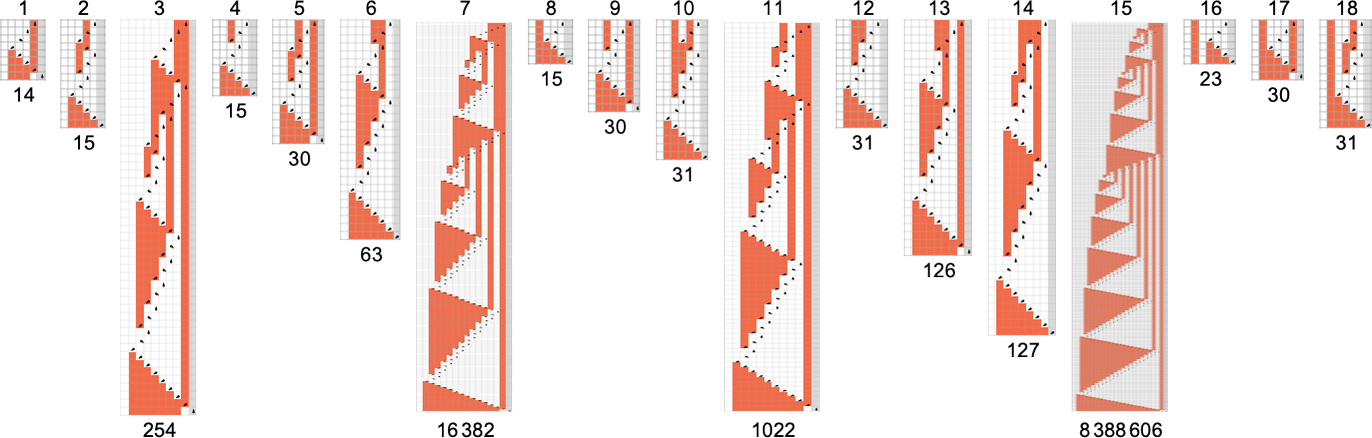

We discussed above that out of the 2.99 million possible

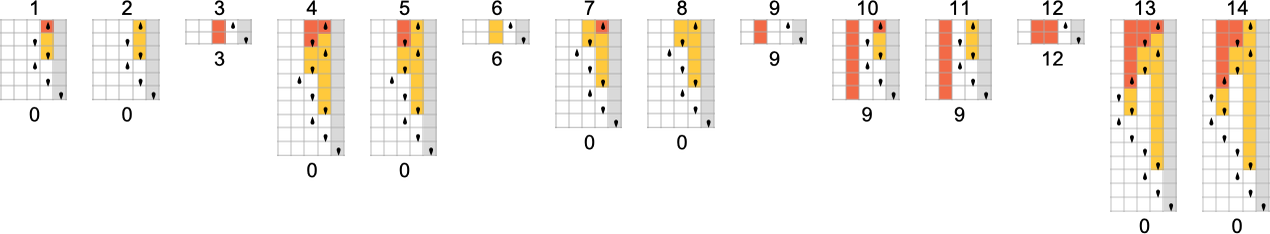

There are machines that give asymptotically constant runtime

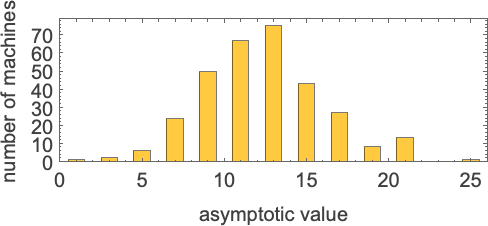

with all odd asymptotic runtime values up to 21 (along with 25) being possible:

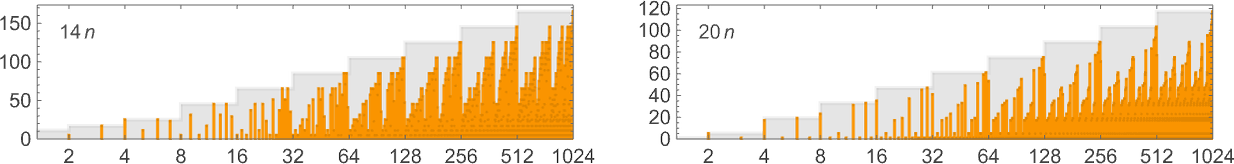

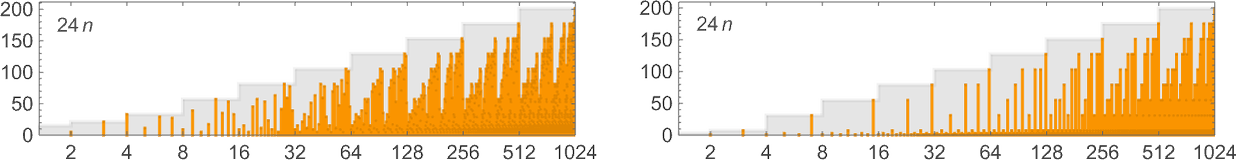

Then there are machines that give asymptotically linear runtimes, with even coefficients from 2 to 20 (along with 24)—for example:

By the way, note that (as we mentioned before) some machines realize their worst-case runtimes for many specific inputs, while in other machines such runtimes are rare (here illustrated for machines with asymptotic runtimes 24n):

Sometimes there are machines whose worst-case runtimes increase linearly, but in effect with fractional slopes:

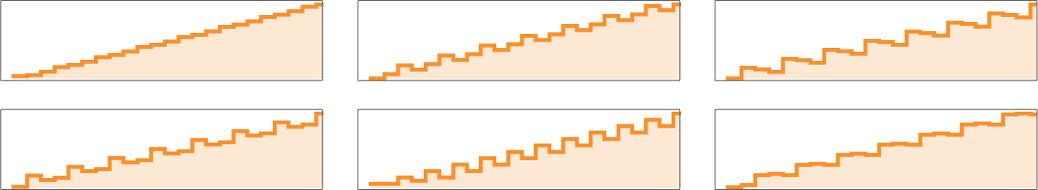

There are many machines whose worst-case runtimes increase in an ultimately linear way—but with “oscillations”:

Averaging out the oscillations gives an overall growth rate of the form αn, where α is an integer or rational number with (as it turns out) denominator 2 or 3; the possible values for α are:

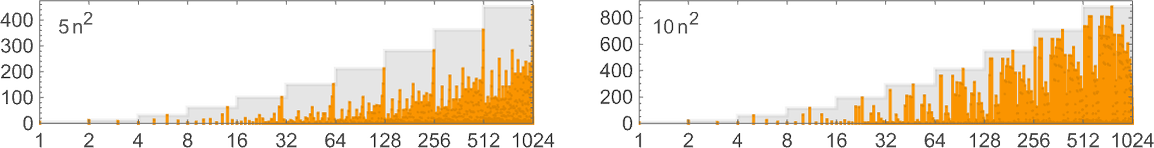

There are also machines with worst-case runtimes growing like αn2, with α an integer from 1 to 10 (though missing 7):

And then there are a few machines (such as 129559 and 1166261) with cubic growth rates.

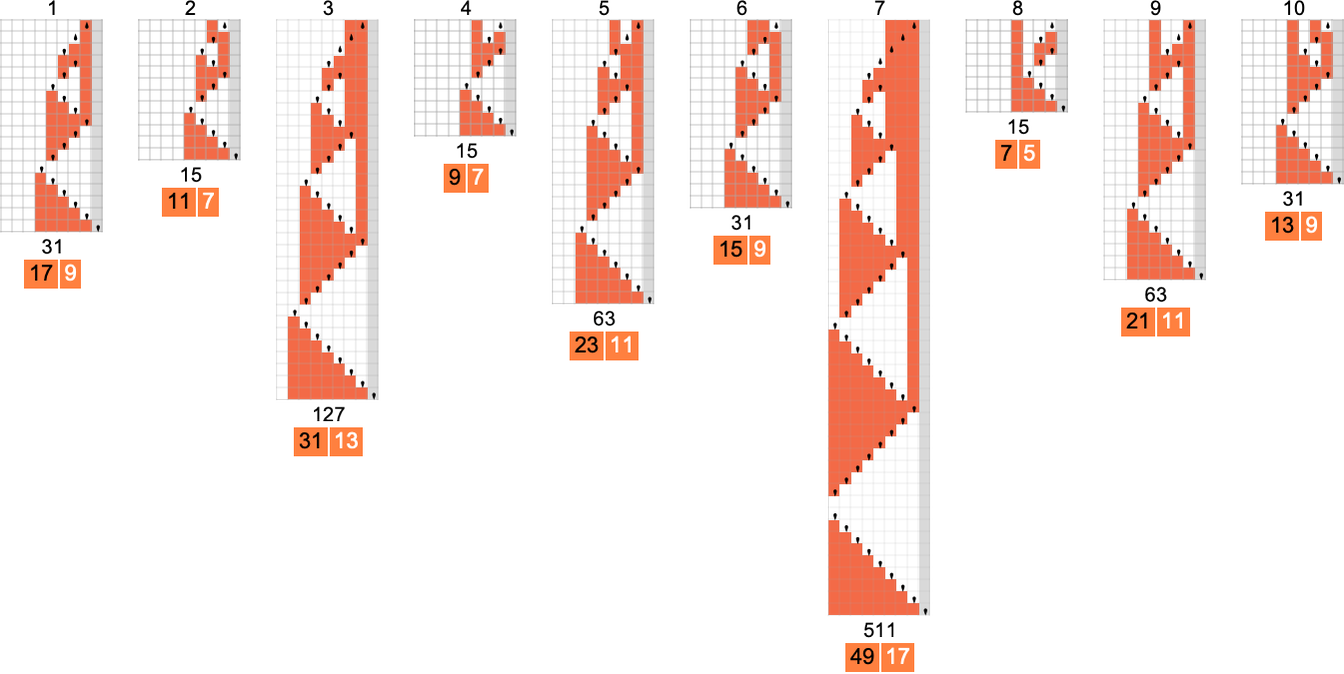

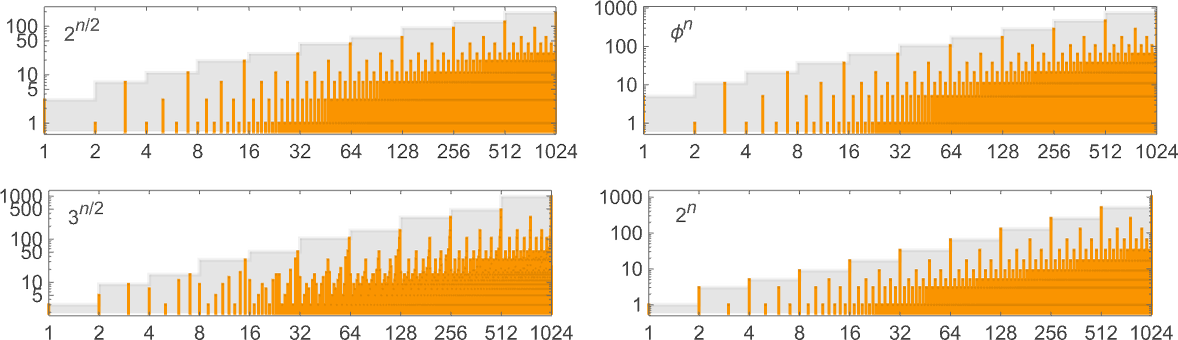

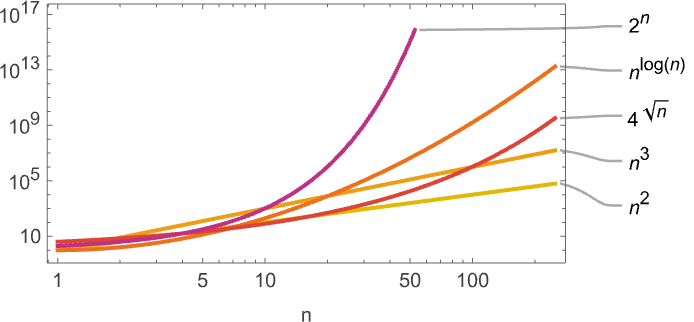

The next—and, in fact, single largest—group of machines have worst-case runtimes that asymptotically grow exponentially, following linear recurrences. The possible asymptotic growth rates seem to be (ϕ is the golden ratio ![]() ):

):

Some particular examples of machines with these growth rates include (we’ll see 5n/2 and 4n examples in the next section):

The first of these is machine 1020827, and the exact worst-case runtime for input size n in this case is:

The second case shown (machine 117245) has exact worst-case runtime

which satisfies the linear recurrence:

The third case (machine 1007039) has exact worst-case runtime:

It’s notable that in all of these cases, the maximum runtime for input size n occurs for input

Continuing and squashing the results, it becomes clear that there’s a nested structure to these patterns:

By the way, it’s certainly not necessary that the worst-case runtime must occur at the largest input of a given size. Here’s an example (machine 888388) where that’s not what happens

and where in the end the 2n/2 growth is achieved by having the same worst-case runtime for input sizes n and n + 1 for all even n:

One feature of everything we’ve seen here is the runtimes we’ve deduced are either asymptotically powers or asymptotically exponentials. There’s nothing in between—for example nothing like nLog[n] or 4Sqrt[n]:

No doubt there are Turing machines with such intermediate growth, but apparently none with

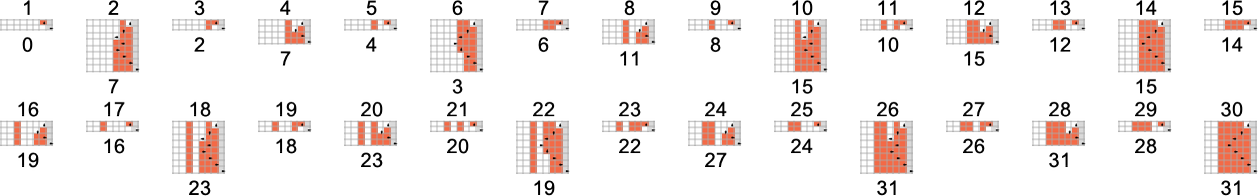

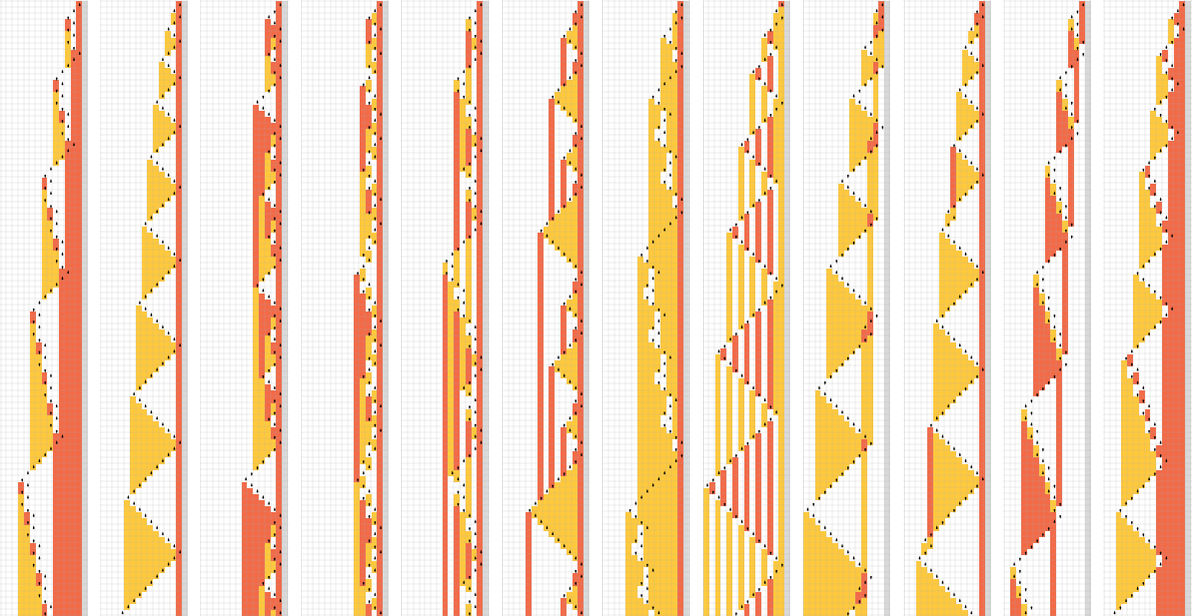

Functions and Their Runtimes in s = 3, k = 2 Turing Machines

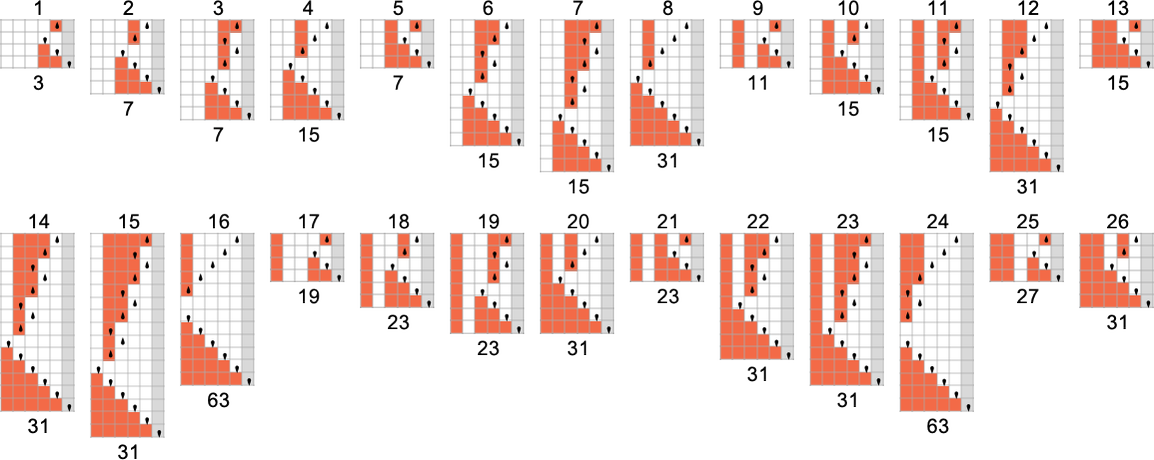

As we discussed above, out of the 2.99 million possible

The functions computed by the most machines are (where, not surprisingly, the identity function

The minimum number of machines that can compute a given function is always 2—because there’s always one machine with a ![]() transition, and another with a

transition, and another with a ![]() transition, as in:

transition, as in:

But altogether there are about 13,000 of these “isolate” machines, where no other

So what are these functions—and how long do they take to compute? And remember, these are functions that are computed by isolate machines—so whatever the runtime of those machines is, this can be thought of as defining a lower bound on the runtime to compute that function, at least by any

So what are the functions with the longest runtimes computed by isolate machines? The overall winner seems to be the function computed by machine 600720 that we discussed above.

Next appears to come machine 589111

with its asymptotically 4n runtime:

And although the values here, say for

Next appear to come machines like 599063

with asymptotic

Despite the seemingly somewhat regular pattern of values for this function, the machine that computes it is an isolate, so we know that at least among

What about the other machines with asymptotically exponential runtimes that we saw in the previous section? Well, the particular machines we used as examples there aren’t even close to isolates. But there are other machines that have the same exponentially growing runtimes, and that are isolates. And, just for once, there’s a surprise.

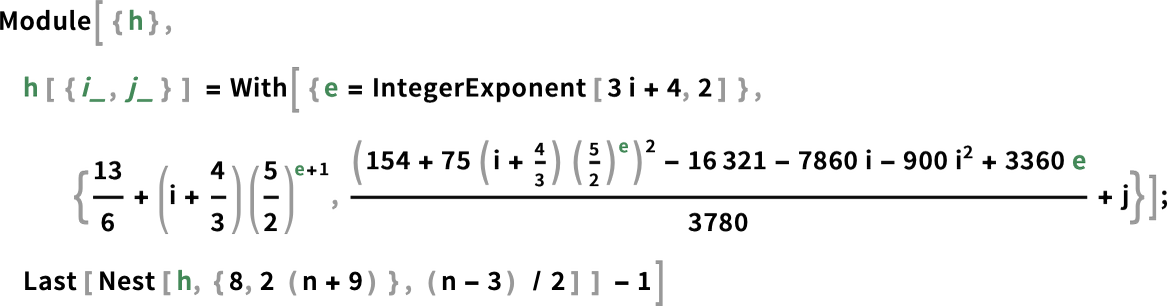

For asymptotic runtime 2n, it turns out that there is just a single isolate machine: 1342057:

But look at how simple the function this machine computes is. In fact,

But despite the simplicity of this, it still takes the Turing machine worst-case runtime ![]() – 1

– 1

And, yes, after a transient at the beginning, all the machine is ultimately doing is to compute

Going on to asymptotic runtimes of the form 3n/2, it turns out there’s only one function for which there’s a machine (1007039) with this asymptotic runtime—and this function can be computed by over a hundred machines, many with faster runtimes, though some with slower (2n) runtimes (e.g. 879123).

What about asymptotic runtimes of order ![]() ? It’s more or less the same story as with 3n/2. There are 48 functions which can be computed by machines with this worst-case runtime. But in all cases there are also many other machines, with many other runtimes, that compute the same functions.

? It’s more or less the same story as with 3n/2. There are 48 functions which can be computed by machines with this worst-case runtime. But in all cases there are also many other machines, with many other runtimes, that compute the same functions.

But now there’s another surprise. For asymptotic runtime 2n/2 there are two functions computed only by isolate machines (889249 and 1073017):

So, once again, these functions have the feature that they can’t be computed any faster by any other

When we looked at

Among

There are, of course, many more

Isolate machines immediately define lower bounds on runtime for the functions they compute. But in general (as we saw above) there can be many machines that compute a given function. For example, as mentioned above, there are 210,792

with asymptotic runtimes ranging from constant to linear, quadratic and exponential. (The most rapidly increasing runtime is ~2n.)

For each function that can be computed, there’s a slightly different collection of runtime profiles; here are the ones for the functions computed by the next largest numbers of machines:

Can Bigger Machines Compute Functions Faster?

We saw above that there are functions which cannot be computed asymptotically faster than particular bounds by, say, any

The first thing to say is that (as we discussed before for

Among

where the exact worst-case runtime is:

But now we can ask whether this function can be computed faster by any

An example is machine 1069163:

We can think of what’s happening as being that we start from the

and in effect optimize this by using a slightly more complicated “instruction set”:

In looking at

As an example, consider the function computed by the isolate machine 1342057:

This has asymptotic runtime 4n. But now if we look at

There are also machines with linearly and quadratically increasing runtimes—though, confusingly, for the first few input sizes, they seem to be increasing just as fast as our original

Here are the underlying rules for these particular Turing machines:

And here’s the full spectrum of runtime profiles achieved by

There are runtimes that are easy to recognize as exponentials—though with bases like 2,![]() , 3/2,

, 3/2, ![]() that are smaller than 4. Then there are linear and polynomial runtimes of the kind we just saw. And there’s some slightly exotic “oscillatory” behavior, like with machine 1418699063

that are smaller than 4. Then there are linear and polynomial runtimes of the kind we just saw. And there’s some slightly exotic “oscillatory” behavior, like with machine 1418699063

that seems to settle down to a periodic sequence of ratios, growing asymptotically like 2n/4.

What about other functions that are difficult to compute by

One of these follows exactly the runtimes of 600720; the other is not the same, but is very close, with about half the runtimes being the same, and the other half having maximal differences that grow linearly with n.

And what this means is that—unlike the function computed by

Looking at other functions that are “hard to compute” with

With a Sufficiently Large Turing Machine…

We’ve been talking so far about very small Turing machines—with at most a handful of distinct cases in their rules. But what if we consider much larger Turing machines? Would these allow us to systematically do computations much faster?

Given a particular (finite) mapping from input to output values, say

it’s quite straightforward to construct a Turing machine

whose state transitions in effect just “immediately look up” these values:

(If we try to compute a value that hasn’t been defined, the Turing machine will simply not halt.)

If we stay with a fixed value of k, then for a “function lookup table” of size v, the number of states we need for a “direct representation” of the lookup table is directly proportional to v. Meanwhile, the runtime is just equal to the absolute lower bound we discussed above, which is linearly proportional to the sizes of input and output.

Of course, with this setup, as we increase v we increase the size of the Turing machine. And we can’t guarantee to encode a function defined, say, for all integers, with anything less than an infinite Turing machine.

But by the time we’re dealing with an infinite Turing machine we don’t really need to be computing anything; we can just be looking everything up. And indeed computation theory always in effect assumes that we’re limiting the size of our machines. And as soon as we do this, there starts to be all sorts of richness in questions like which functions are computable, and what runtime is required to compute them.

In the past, we might just have assumed that there is some arbitrary bound on the size of Turing machines, or, in effect, a bound on their “algorithmic information content” or “program size”. But the point of what we’re doing here is to explore what happens not with arbitrary bounds, but with bounds that are small enough to allow us to do exhaustive empirical investigations.

In other words, we’re restricting ourselves to low algorithmic (or program) complexity and

asking what then happens with time complexity, space complexity, etc. And what we find is that even in that domain, there’s remarkable richness in the behavior we’re able to see. And from the Principle of Computational Equivalence we can expect that this richness is already characteristic of what we’d see even with much larger Turing machines, and thus larger algorithmic complexity.

Beyond Binary Turing Machines

In everything we’ve done so far, we’ve been looking at “binary” (i.e.

The setup we’ve been using translates immediately:

The simplest case is

Of these machines, 88 always halt—and compute 77 distinct functions. The possible runtimes are:

And unlike what we saw even for

For s = 2, k = 3, we have

In both cases, of the machines that don’t halt, the vast majority become periodic. For

Just as for

or in squashed form:

If we look beyond input 1, we find that about 1.12 million

A notable feature is that the tail consists of functions computed by only one machine. In the ![]() and

and ![]() means that there are always at least two machines computing a given function. But with

means that there are always at least two machines computing a given function. But with

What about runtimes? The results for

In a sense it should not be surprising that there is so much similarity between the behavior of

However, if we look not at the kind of “one-sided” (or “halt if you go to the right”) Turing machines we are considering here, but instead at Turing machines where the head can go freely in either direction, then one difference emerges. Starting with a blank tape, all

And this fact provides a clue that such a machine (or, actually, the 14 essentially equivalent machines of which this is one example) might be capable of universal computation. And indeed it can be shown that—at least with appropriate (infinite) initial conditions, the machine can successfully be “programmed” to emulate systems that are known to be universal, thereby proving that it itself is universal.

How does this machine fare with our one-sided setup? Here’s what it does with the first few inputs:

And what one finds is that for any input, the head of the machine eventually goes to the right, so with our one-sided setup we consider the machine to halt:

It turns out that the worst-case runtime for input of size n grows according to:

But if we look at the function computed by this machine we can ask whether there are ways to compute it faster. And it turns out there are 11 other s = 2, k = 3 machines (though, for example, no

one might think they would be simple enough to have shorter runtimes. But in fact in the one-sided setup their behavior is basically identical to our original machine.

OK, but what about

Recognizable Functions

We’ve been talking a lot about how fast Turing machines can compute functions. But what can we say about what functions they compute? With appropriate encoding of inputs and decoding of outputs, we know that (essentially by definition) any computable function can be computed by some Turing machine. But what about the simple Turing machines we’ve been using here? And what about “without encodings”?

The way we’ve set things up, we’re taking both the input and the output to our Turing machines to be the sequences of values on their tapes—and we’re interpreting these values as digits of integers. So that means we can think of our Turing machines as defining functions from integers to integers. But what functions are they?

Here are two

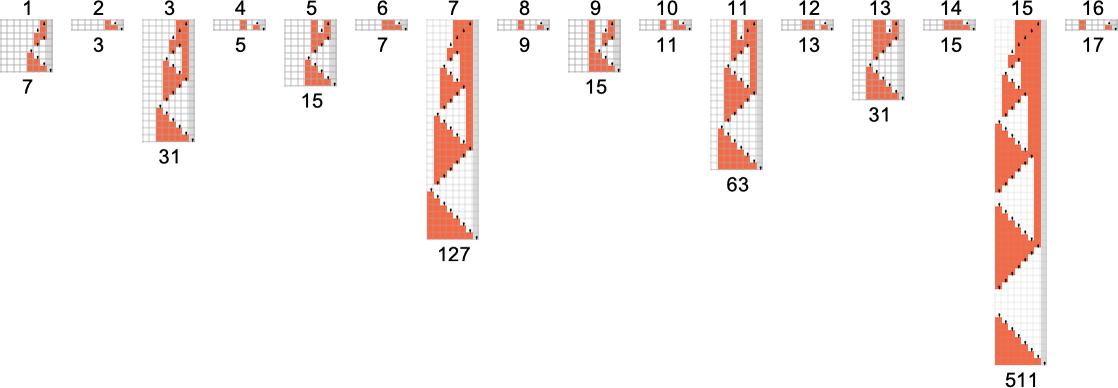

There are a total of 17

Still, for

If we restrict ourselves to even inputs, then we can compute

Similarly, there are

What about other “mathematically simple” functions, say

We’ve already seen a variety of examples where our Turing machines can be interpreted as evaluating bitwise functions of their inputs. A more minimal case would be something like a single bitflip—and indeed there is an

To be able to flip a higher-order digit, one needs a Turing machine with more states. There are two

And in general—as these pictures suggest—flipping the mth bit can be done with a Turing machine with at least

What about Turing machines that compute periodic functions? Strict (nontrivial) periodicity seems difficult to achieve. But here, for example, is an

With both

Another thing one might ask is whether one Turing machine can emulate another. And indeed that’s what we see happening—very directly—whenever one Turing machine computes the same function as another.

(We also know that there exist universal Turing machines—the simplest having

Empirical Computational Irreducibility

Computational irreducibility has been central to much of the science I’ve done in the past four decades or so. And indeed it’s guided our intuition in much of what we’ve been exploring here. But the things we’ve discussed now also allow us to take an empirical look at the core phenomenon of computational irreducibility itself.

Computational irreducibility is ultimately about the idea that there can be computations where in effect there is no shortcut: there is no way to systematically find their results except by running each of their steps. In other words, given an irreducible computation, there’s basically no way to come up with another computation that gives the same result, but in fewer steps. Needless to say, if one wants to tighten up this intuitive idea, there are lots of detailed issues to consider. For example, what about just using a computational system that has “bigger primitives”? Like many other foundational concepts in theoretical science, it’s difficult to pin down exactly how one should set things up—so that one doesn’t either implicitly assume what one’s trying to explain, or so restrict things that everything becomes essentially trivial.

But using what we’ve done here, we can explore a definite—if restricted—version of computational irreducibility in a very explicit way. Imagine we’re computing a function using a Turing machine. What would it mean to say that that function—and the underlying behavior of the Turing machine that computes it—is computationally irreducible? Essentially it’s that there’s no other faster way to compute that function.

But if we restrict ourselves to computation by a certain size of Turing machine, that’s exactly what we’ve studied at great length here. And, for example, whenever we have what we’ve called an “isolate” Turing machine, we know that no other Turing machine of the same size can compute the same function. So that means one can say that the function is computationally irreducible with respect to Turing machines of the given size.

How robust is such a notion? We’ve seen examples above where a given function can be computed, say, only in exponential time by an

But the important point here is that we can already see a restricted version of computational irreducibility just by looking explicitly at Turing machines of a given size. And this allows us to get concrete results about computational irreducibility, or at least about this restricted version of it.

One of the remarkable discoveries in looking at lots of kinds of systems over the years has been just how common the phenomenon of computational irreducibility seems to be. But usually we haven’t had a way to rigorously say that we’re seeing computational irreducibility in any particular case. All we typically know is that we can’t “visually decode” what’s going on, nor can particular methods we try. (And, yes, the fact that a wide variety of different methods almost always agree about what’s “compressible” and what’s not encourages our conclusions about the presence of computational irreducibility.)

In looking at Turing machines here, we’re often seeing “visual complexity”, not so much in the detailed—often ponderous—behavior with a particular initial condition, but more, for example, in what we get by plotting function values against inputs. But now we have a more rigorous—if restricted—test for computational irreducibility: we can ask whether the function that’s being computed is irreducible with respect to this size of Turing machine, or, typically equivalently, whether the Turing machine we’re looking at is an isolate.

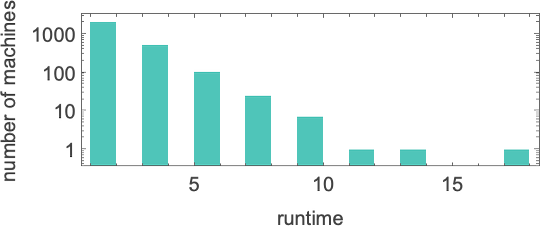

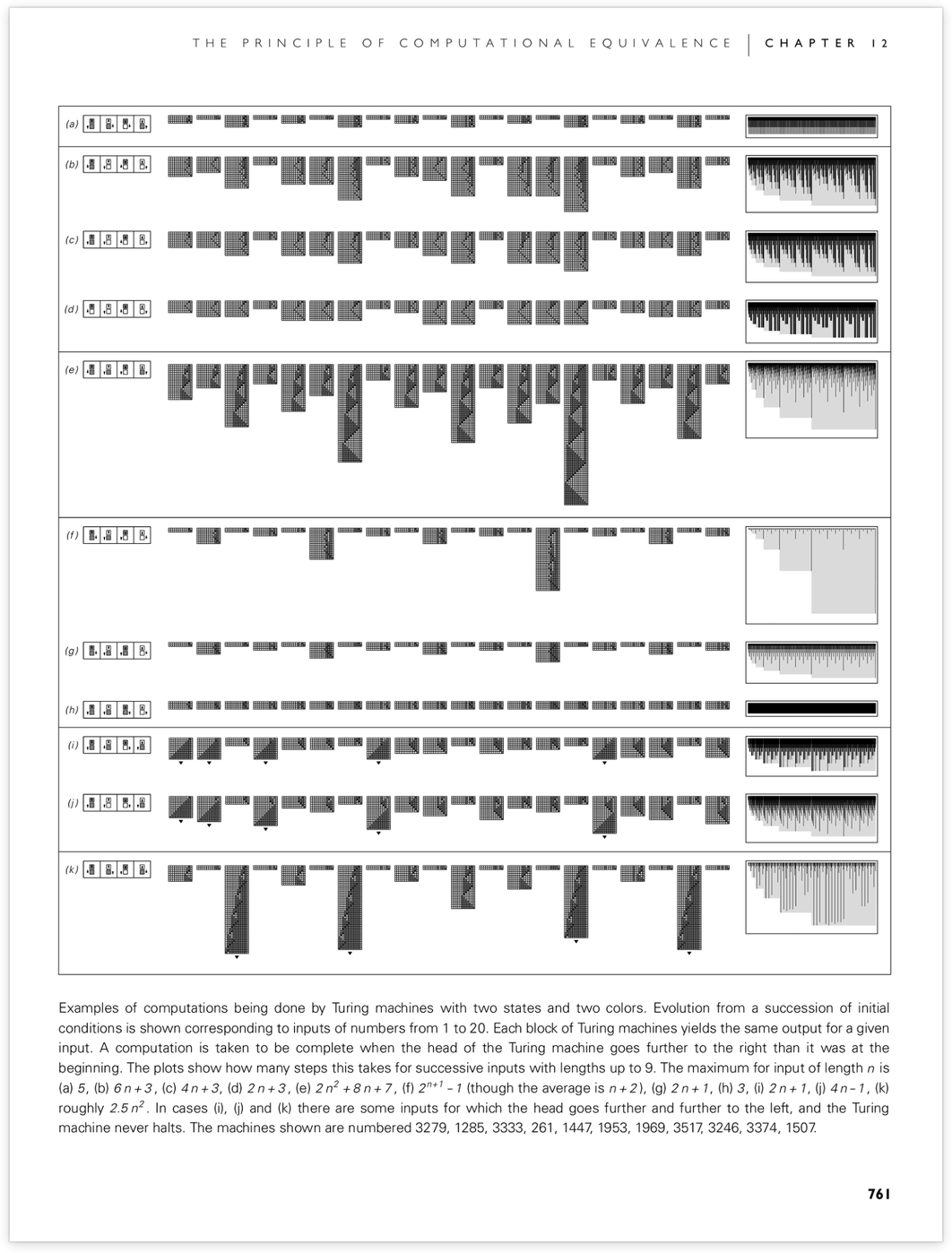

So now we can, for example, explore how common irreducibility defined in this way might be. Here are results for some of the classes of small Turing machines we’ve studied above:

And what we see is that—much like our impression from computational systems like cellular automata—computational irreducibility is indeed very common among small Turing machines, where now we’re using our rigorous, if restricted, notion of computational irreducibility.

(It’s worth commenting that while “global” features of Turing machines—like the functions they compute—may be computationally irreducible, there can still be lots of computational reducibility in their more detailed properties. And indeed what we’ve seen here is that there are plenty of features of the behavior of Turing machines—like the back-and-forth motion of their heads—that look visually simple, and that we can expect to compute in dramatically faster ways than just running the Turing machine itself.)

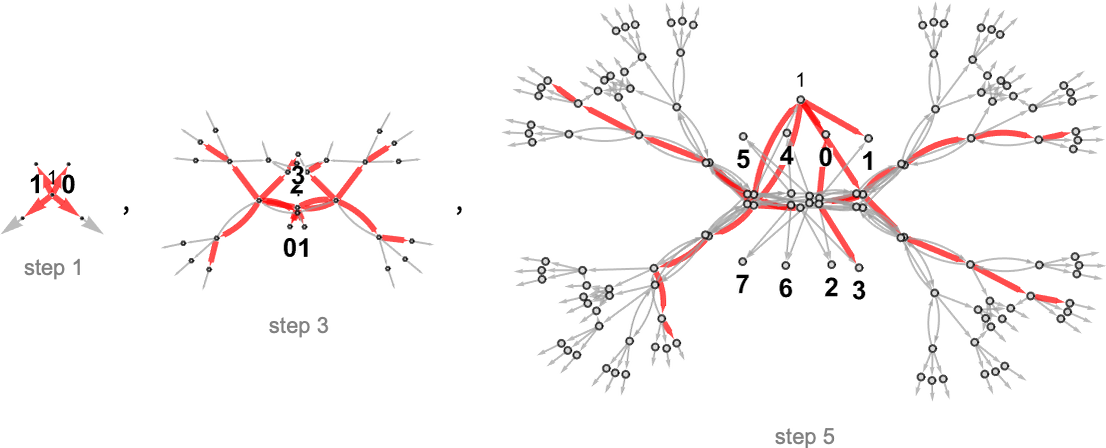

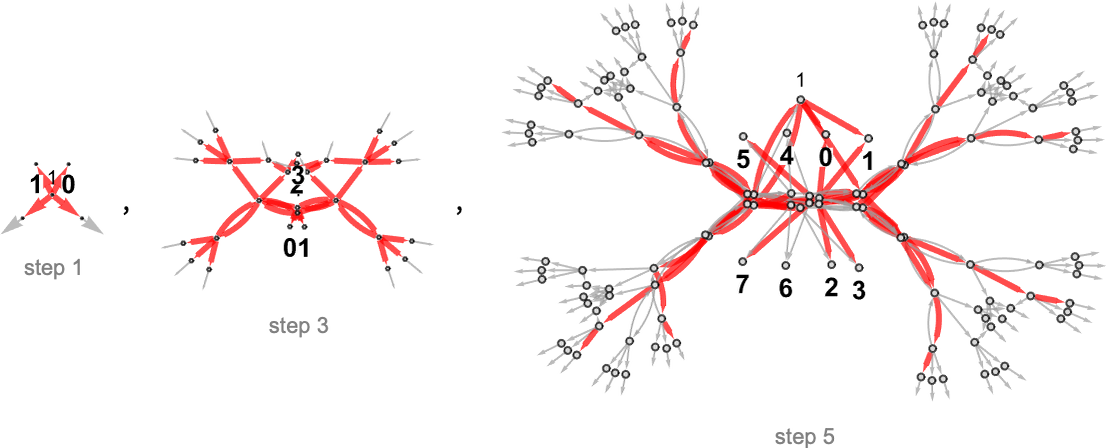

Nondeterministic (Multiway) Turing Machines

So far, we’ve made a fairly extensive study of ordinary, deterministic (“single-way”) Turing machines. But the P vs. NP question is about comparing the capabilities of such deterministic Turing machines with the capabilities of nondeterministic—or multiway—Turing machines.

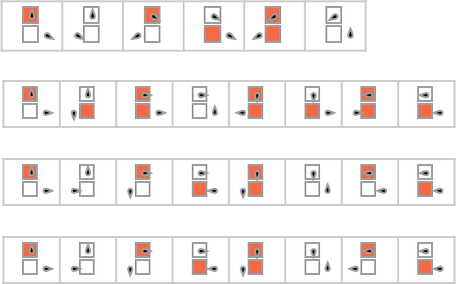

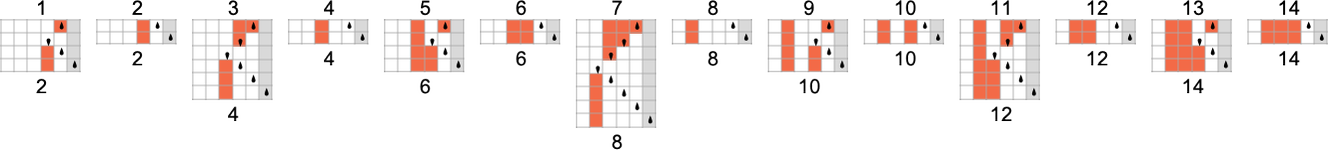

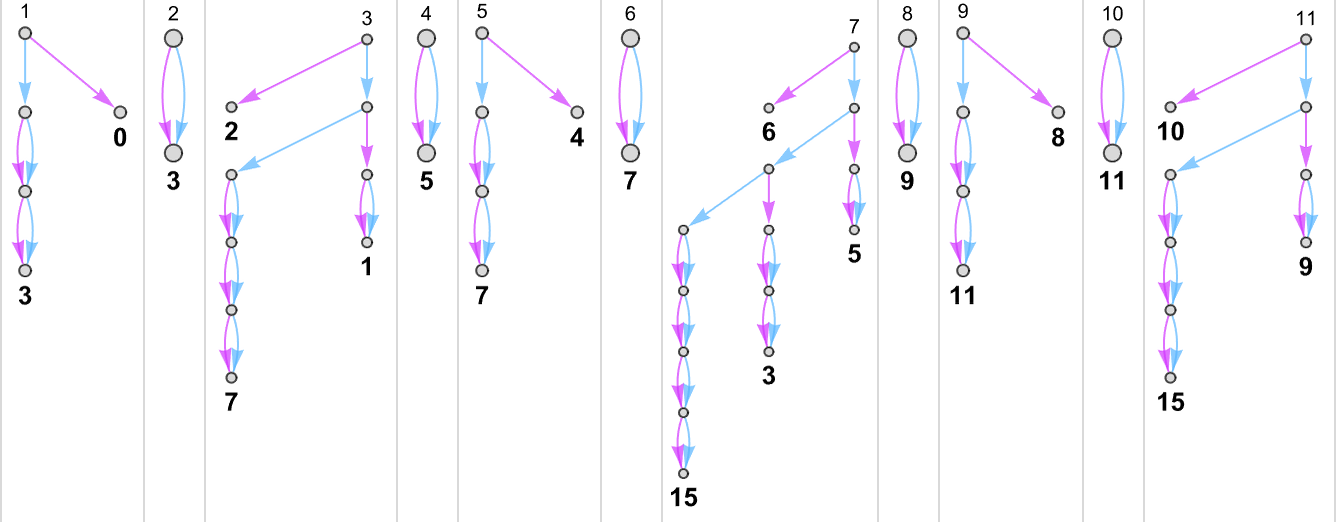

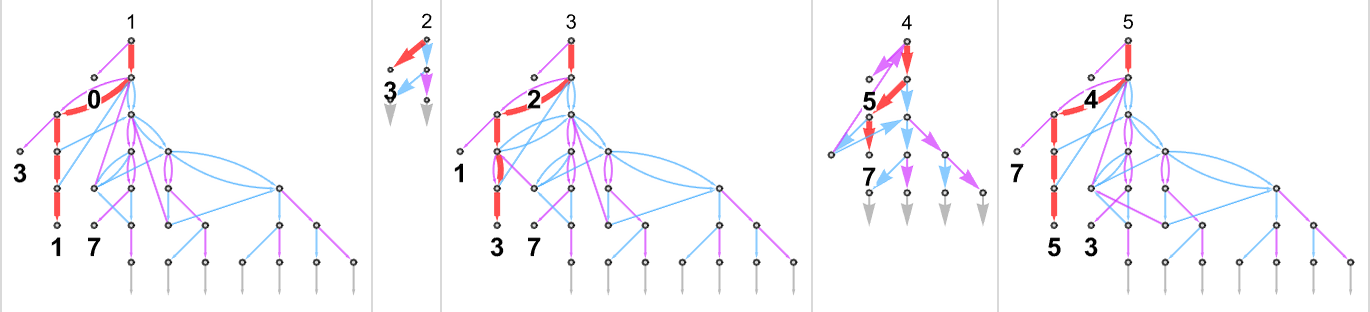

An ordinary (deterministic) Turing machine has a rule such as

that specifies a unique sequence of successive configurations for the Turing machine

which we can represent as:

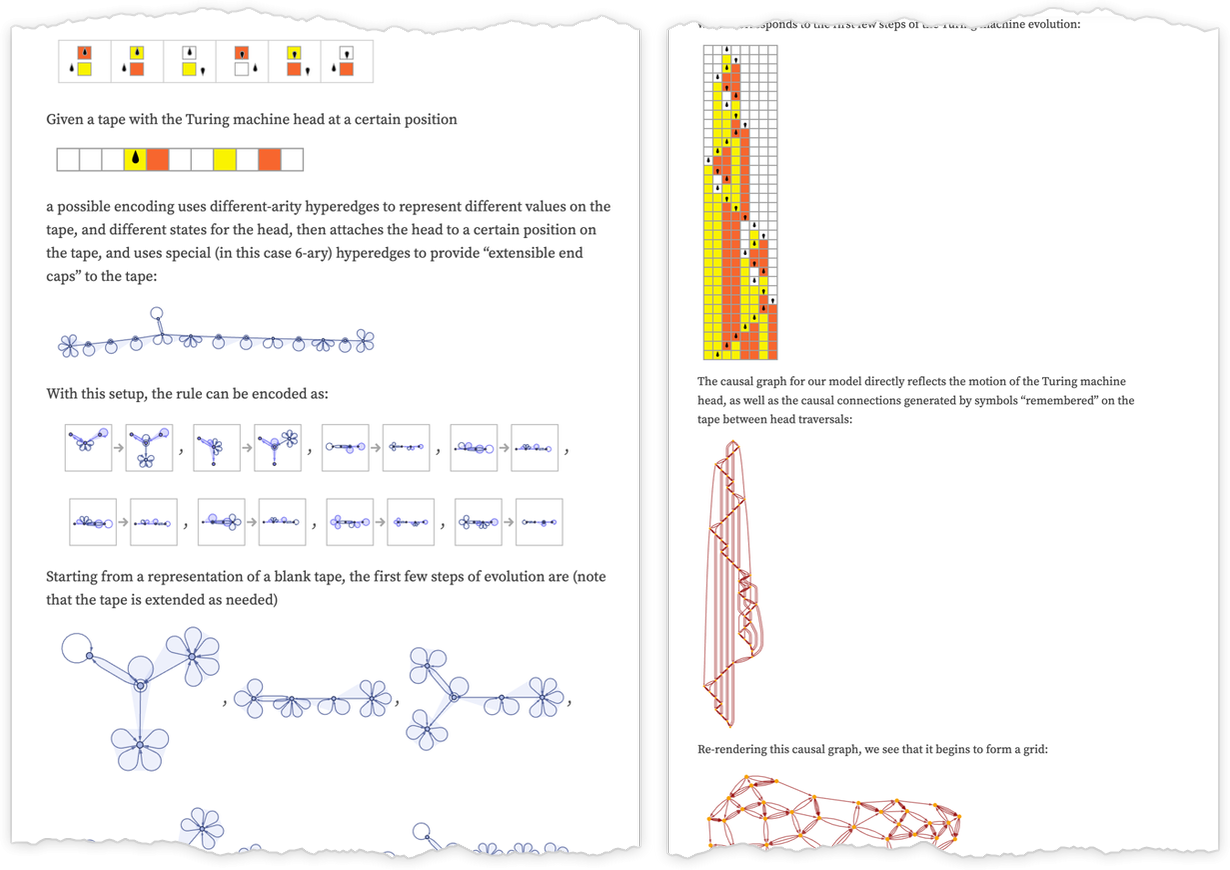

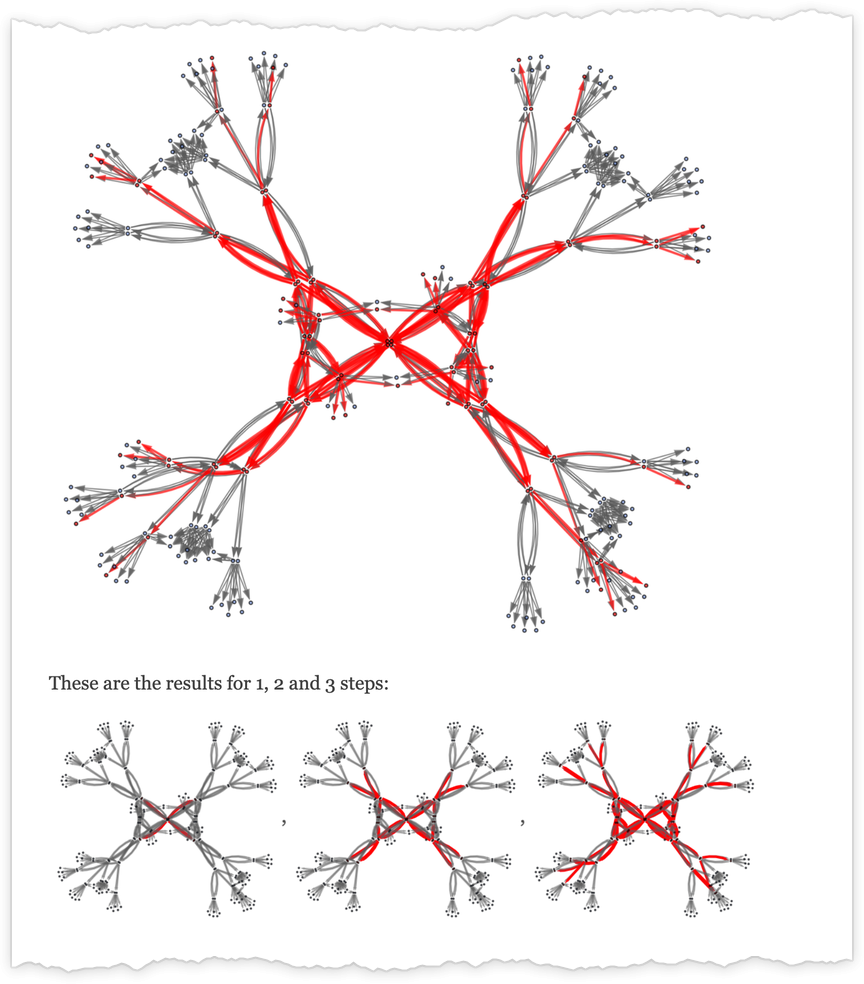

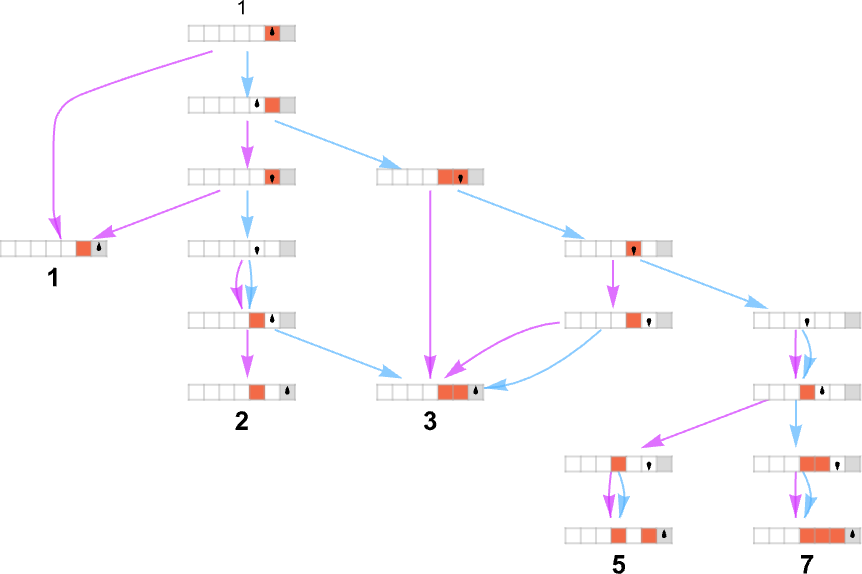

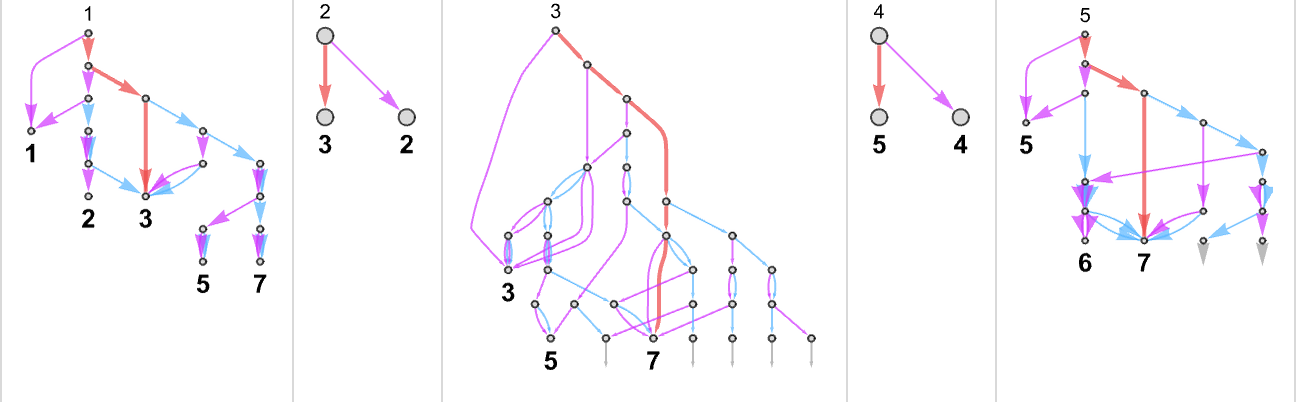

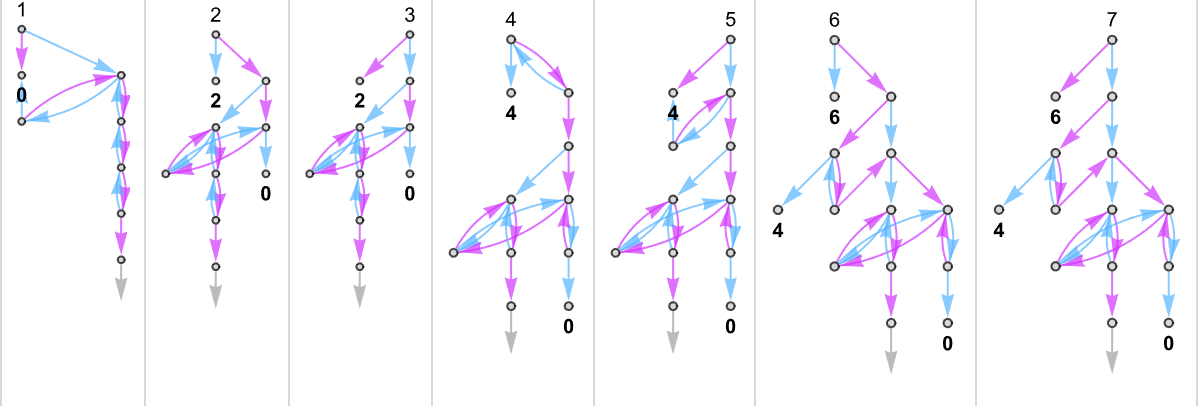

A multiway Turing machine, on the other hand, can have multiple rules, such as

which are applied in all possible ways to generate a whole multiway graph of successive configurations for the Turing machine

where we have indicated edges in the multiway graph associated with the application of each rule respectively by ![]() and

and ![]() , and where identical Turing machine configurations are merged.

, and where identical Turing machine configurations are merged.

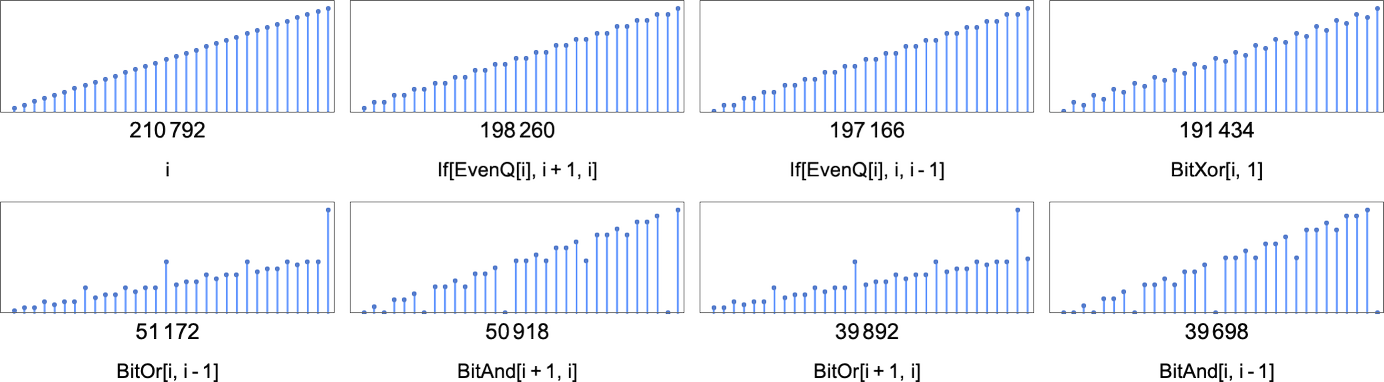

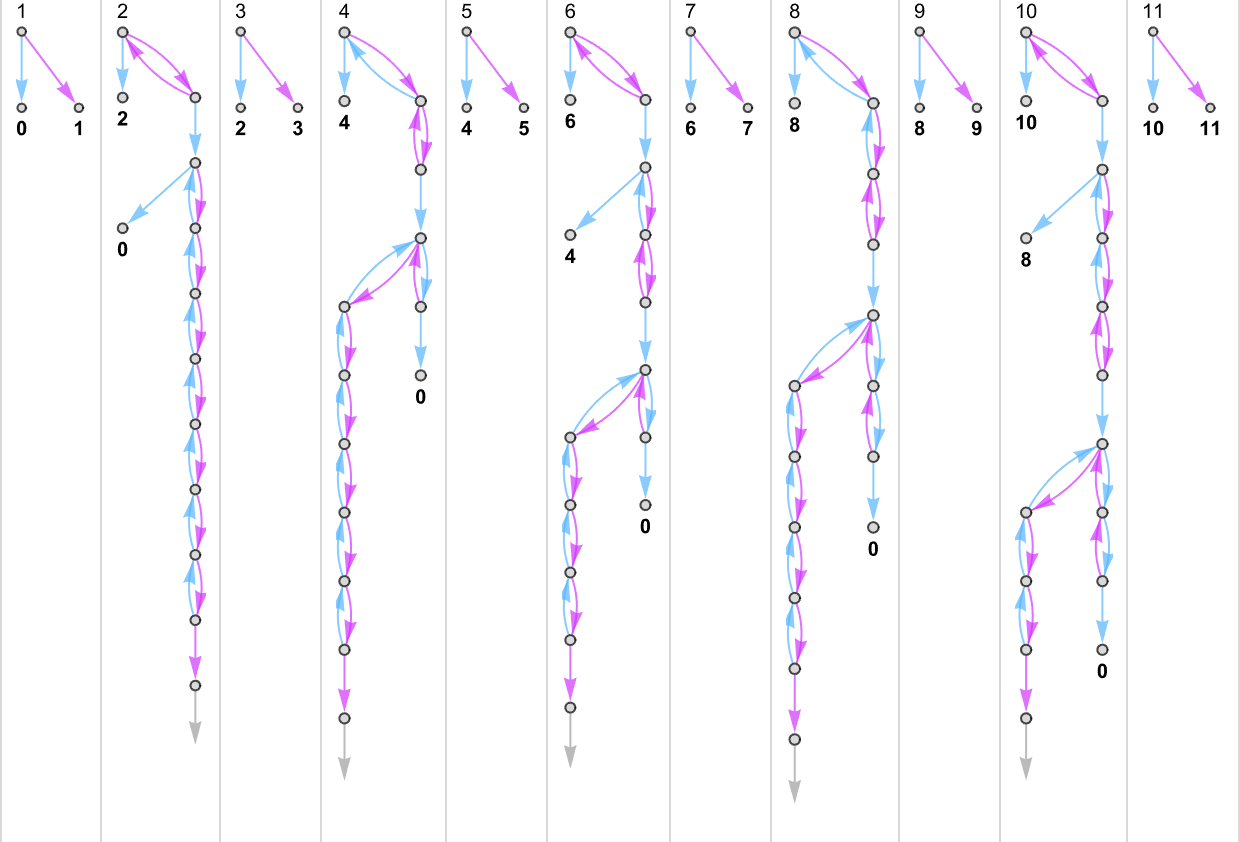

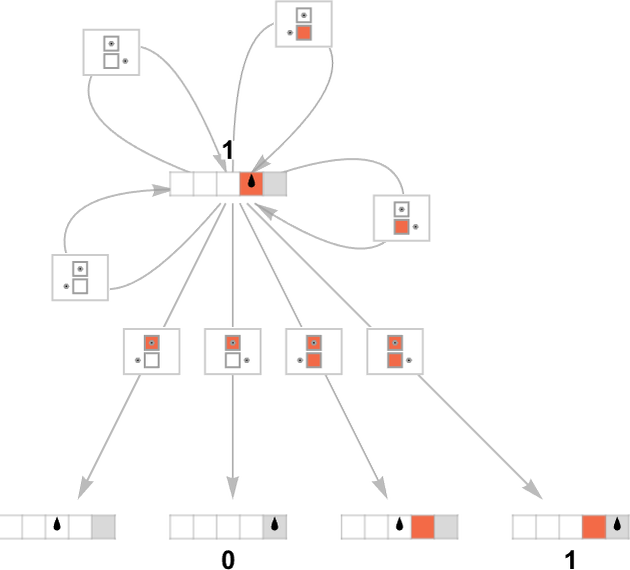

Just as we have done for ordinary (deterministic) Turing machines, we take multiway Turing machines to reach a halting configuration whenever the head goes further to the right than it started—though now this may happen on multiple branches—so that the Turing machine in effect can generate multiple outputs.

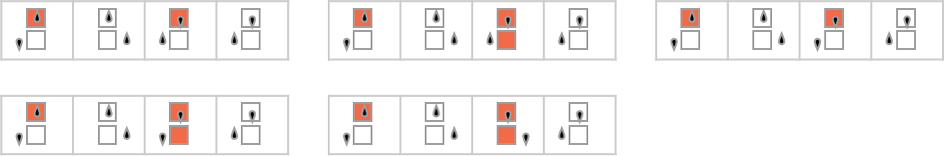

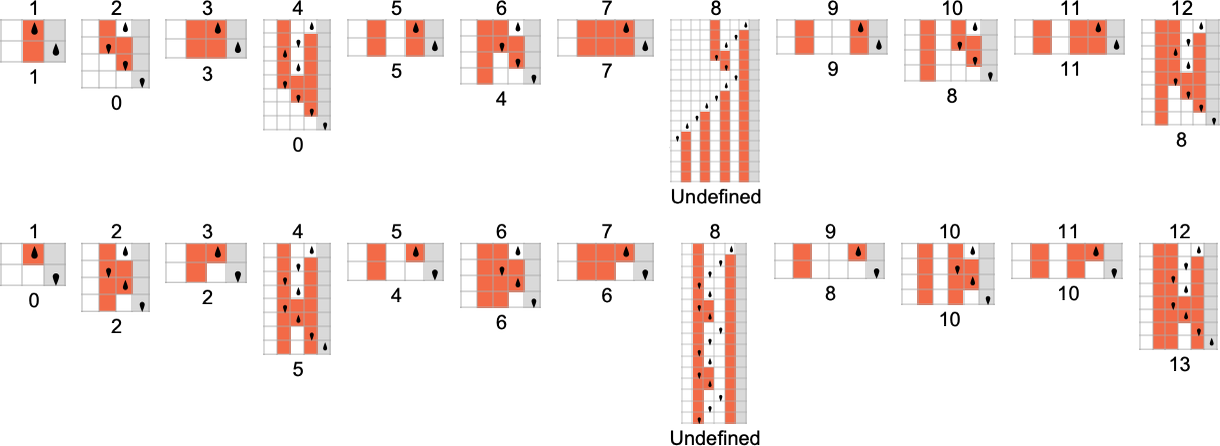

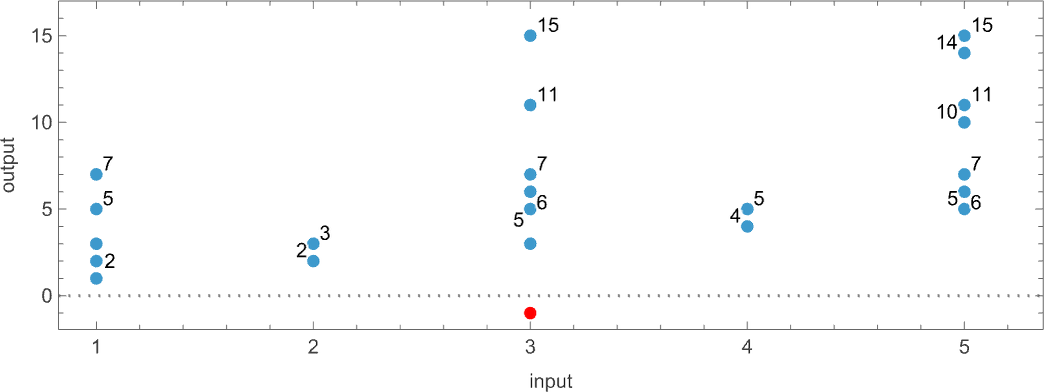

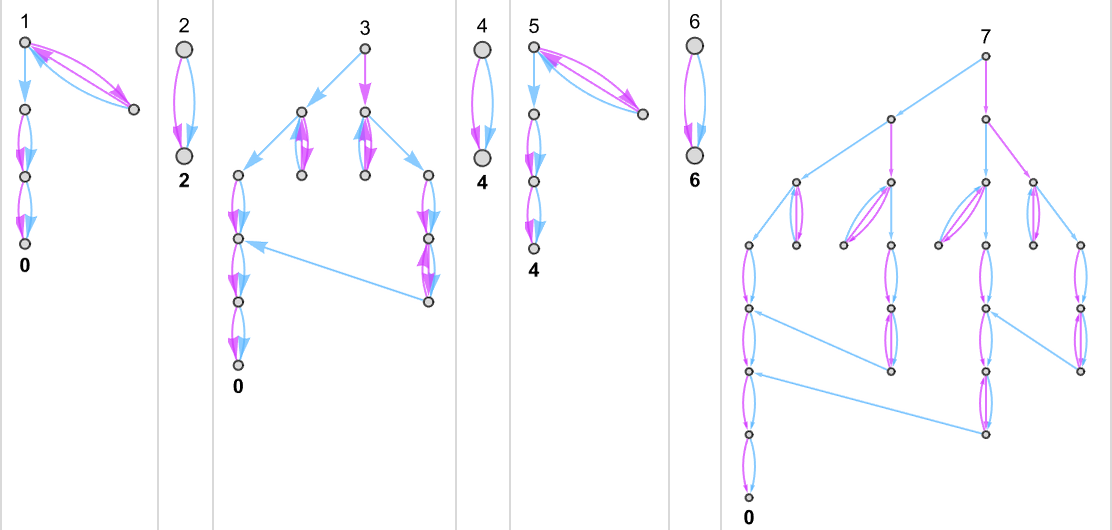

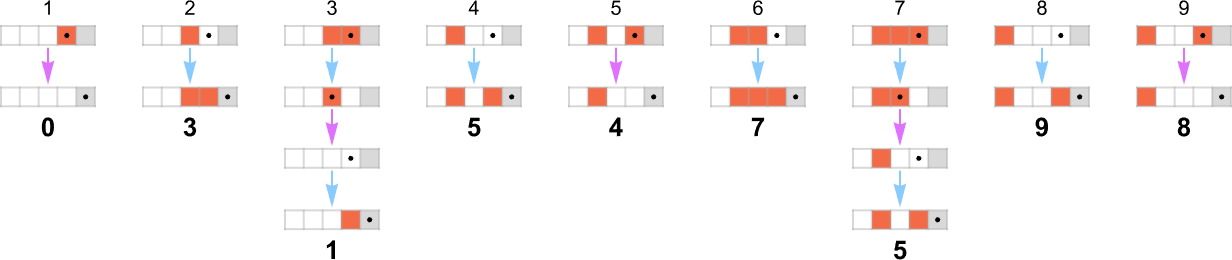

With the way we have set things up, we can think of an ordinary (deterministic) Turing machine as taking an input i and giving as output some value f[i] (where that value might be undefined if the Turing machine doesn’t halt for a given i). In direct analogy, we can think of a multiway Turing machine as taking an input i and giving potentially a whole collection of corresponding outputs:

Among the immediate complications is the fact that the machine may not halt, at least on some branches—as happens for input 3 here, indicated by a red dot in the plot above:

(In addition, we see that there can be multiple paths that lead to a given output, in effect defining multiple runtimes for that output. There can also be cycles, but in defining “runtimes” we ignore these.)

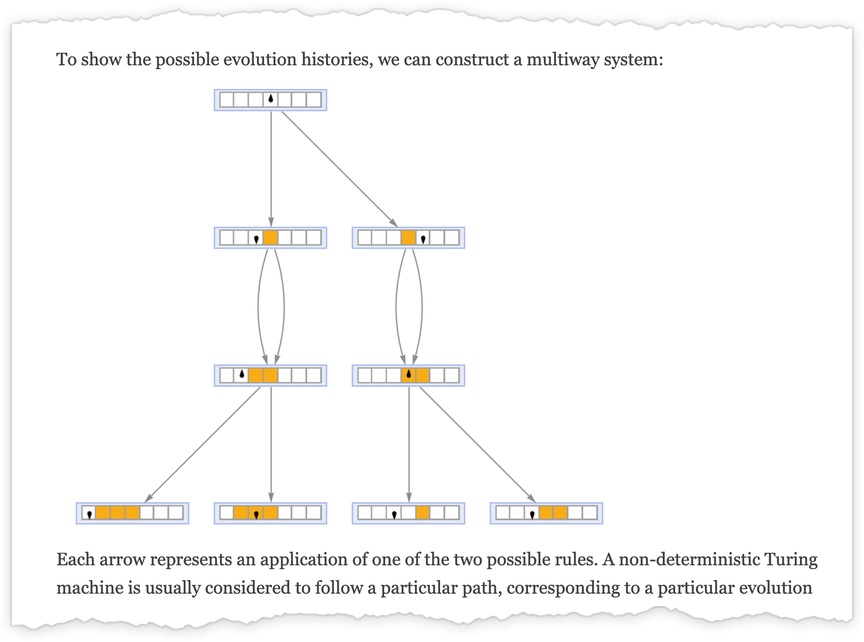

When we construct a multiway graph we are effectively setting up a representation for all possible paths in the evolution of a (multiway) system. But when we talk about nondeterministic evolution we are typically imagining that just a single path is going to be followed, but we don’t know which.

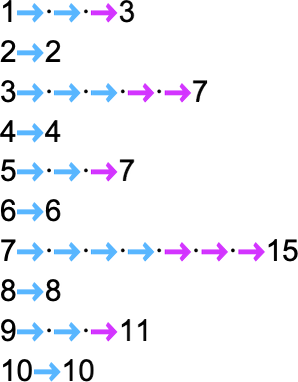

Let’s say that we have a multiway Turing machine that for every given input generates a certain set of outputs. If we were to pick just one of the outputs from each of these sets, we would effectively in each case be picking one path in the multiway Turing machine. Or, in other words, we would be “doing a nondeterministic computation”, or in effect getting output from a nondeterministic Turing machine.

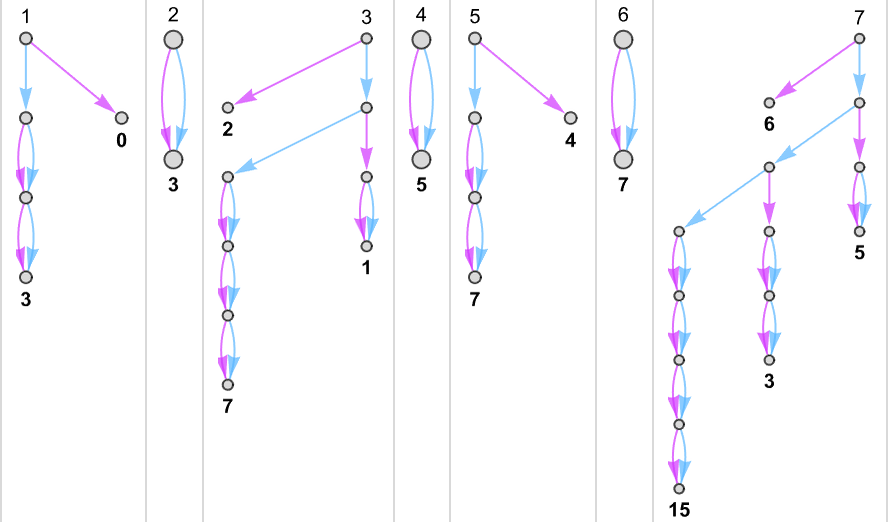

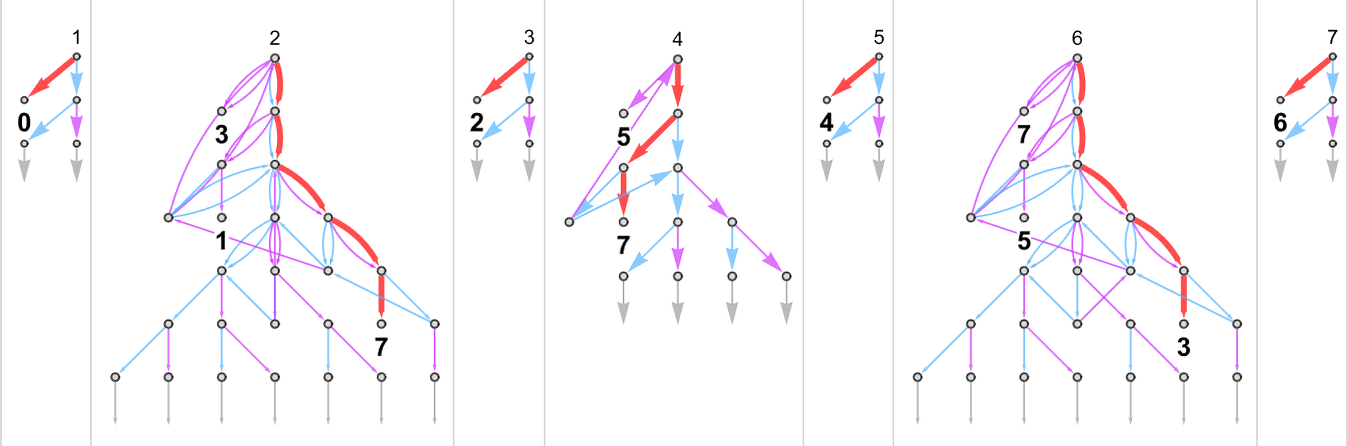

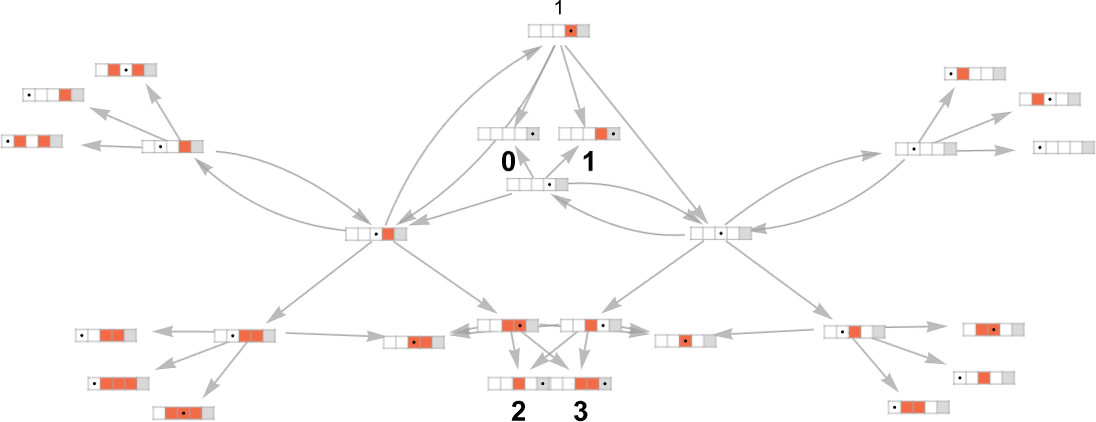

As an example, let’s take our multiway Turing machine from above. Here is an example of how this machine—thought of as a nondeterministic Turing machine—can generate a certain sequence of output values:

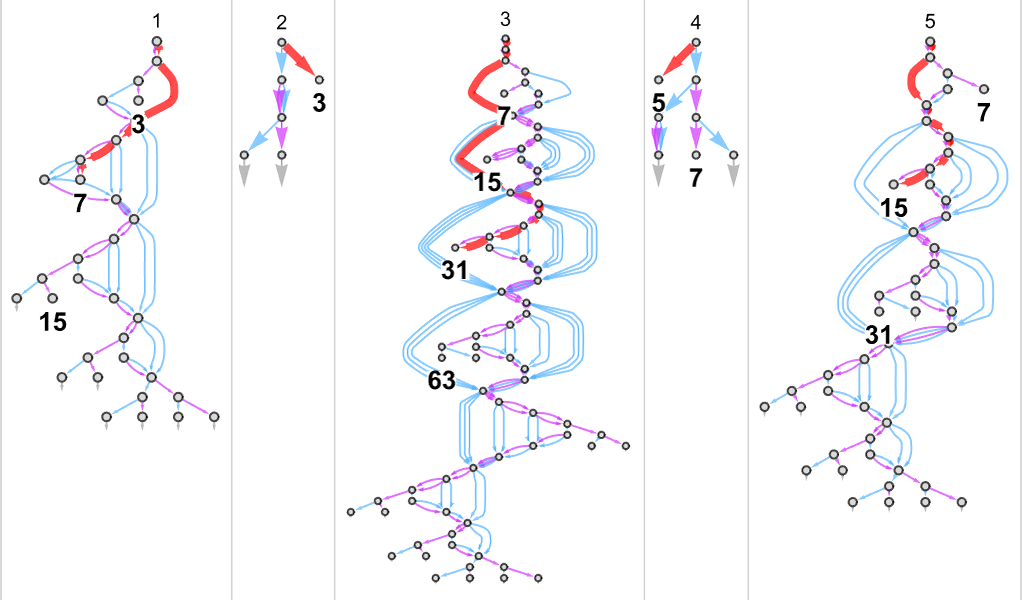

Each of these output values is achieved by following a certain path in the multiway graph obtained with each input:

Keeping only the path taken (and including the underlying Turing machine configuration) this represents how each output value was “derived”:

The length of the path can then be thought of as the runtime required for the nondeterministic Turing machine to reach the output value. (When there are multiple paths to a given output value, we’ll typically consider “the runtime” to be the length of the shortest of these paths.) So now we can summarize the runtimes from our example as follows:

The core of the P vs. NP problem is to compare the runtime for a particular function obtained by deterministic and nondeterministic Turing machines.

So, for example, given a deterministic Turing machine that computes a certain function, we can ask whether there is a nondeterministic Turing machine which—if you picked the right branch—can compute that same function, but faster.

In the case of the example above, there are two possible underlying Turing machine rules indicated by ![]() and

and ![]() . For each input we can choose at each step a different rule to apply in order to get to the output:

. For each input we can choose at each step a different rule to apply in order to get to the output:

The possibility of using different rules at different steps in effect allows much more freedom in how our computation can be done. The P vs. NP question concerns whether this freedom allows one to fundamentally speed up the computation of a given function.

But before we explore that question further, let’s take a look at what multiway (nondeterministic) Turing machines typically do; in other words, let’s study their ruliology.

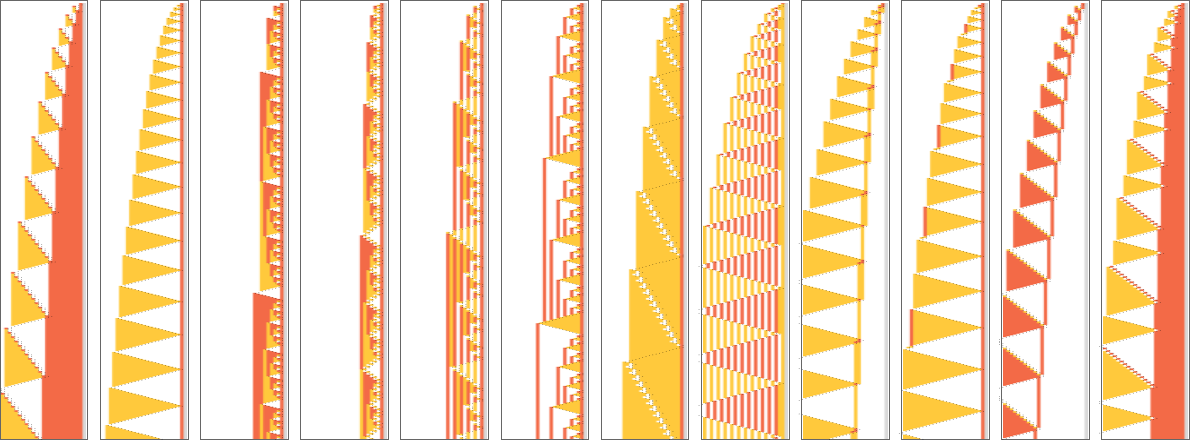

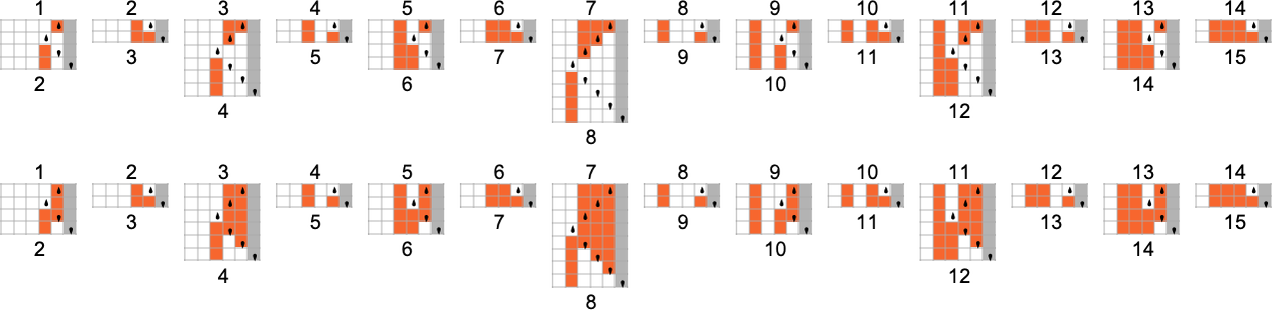

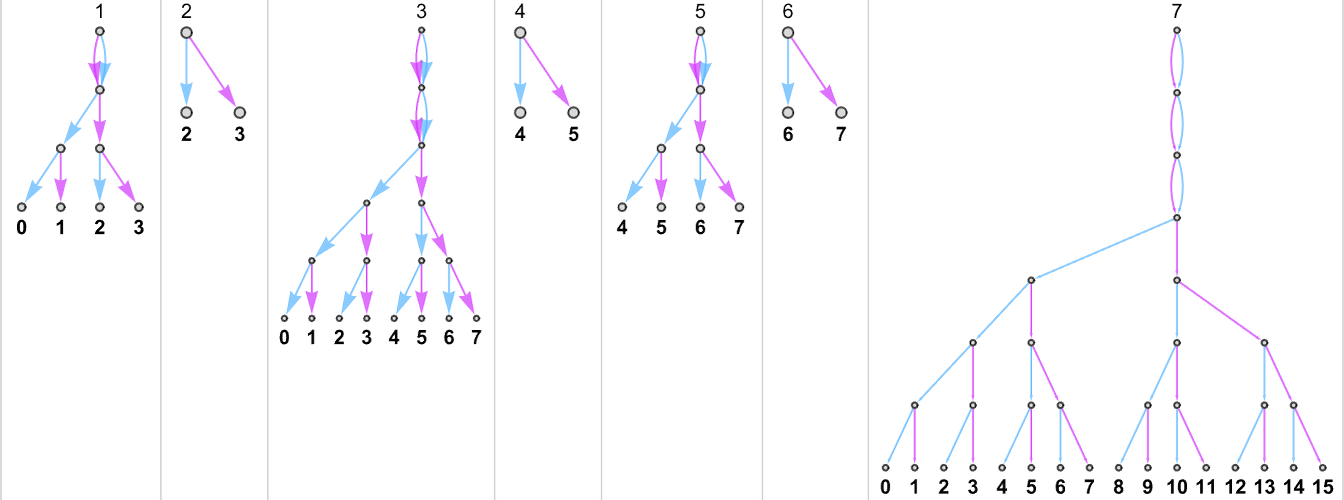

Multiway (Nondeterministic) s = 1, k = 2 Turing Machines

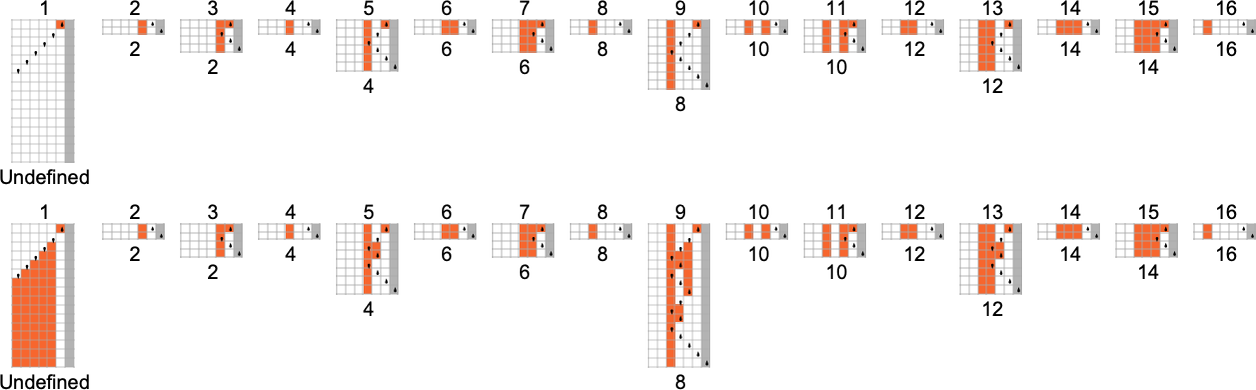

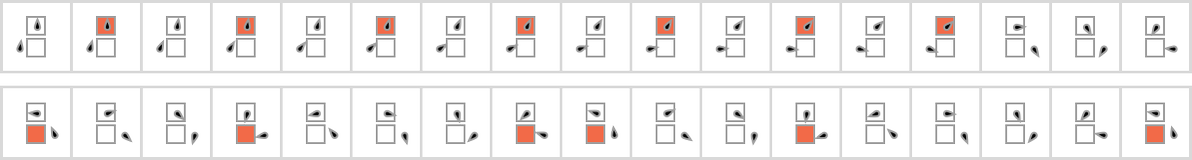

As our first example of doing ruliology for multiway Turing machines, let’s consider the case of pairs of

Sometimes, as in machine {1,9}, there turns out to be a unique output value for every input:

Sometimes, as in machine {5,9}, there is usually a unique value, but sometimes not:

Something similar happens with {3,7}:

There are cases—like {1,3}—where for some inputs there’s a “burst” of possible outputs:

There are also plenty of cases where for some inputs

or for all inputs, there are branches that do not halt:

What about runtimes? Well, for each possible output in a nondeterministic Turing machine, we can see how many steps it takes to reach that output on any branch of the multiway graph, and we can consider that minimum number to be the “nondeterministic runtime” needed to compute that output.

It’s the quintessential setup for NP computations: if you can successfully guess what branch to follow, you can potentially get to an answer quickly. But if you have to explicitly check each branch in turn, that can be a slow process.

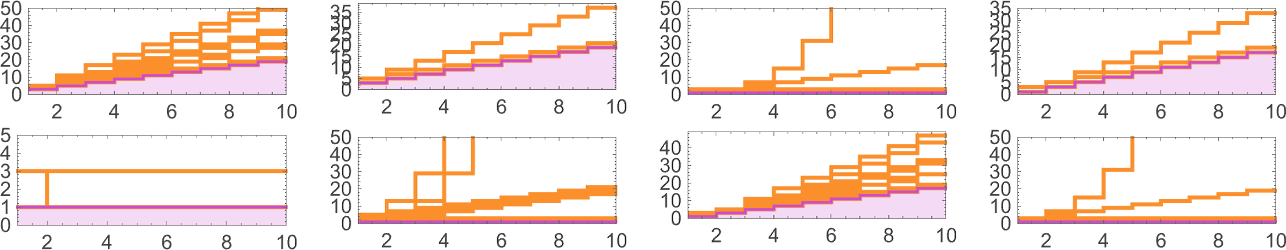

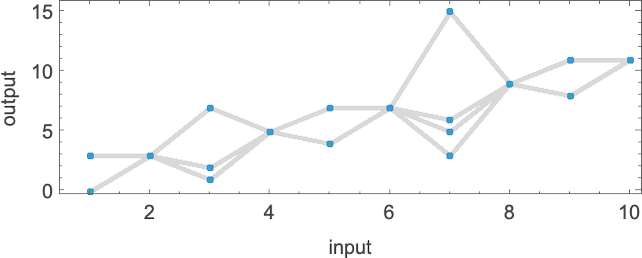

Here’s an example showing possible outputs and possible runtimes for a sequence of inputs for the {3,7} nondeterministic machine

or, combined in 3D:

So what functions can a nondeterministic machine like this “nondeterministically” generate? For each input we have to pick one of the possible corresponding (“multiway”) outputs. And in effect the possible functions correspond to possible “threadings” through these values

or:

To each function one can then associate a “nondeterministic runtime” for each output, here:

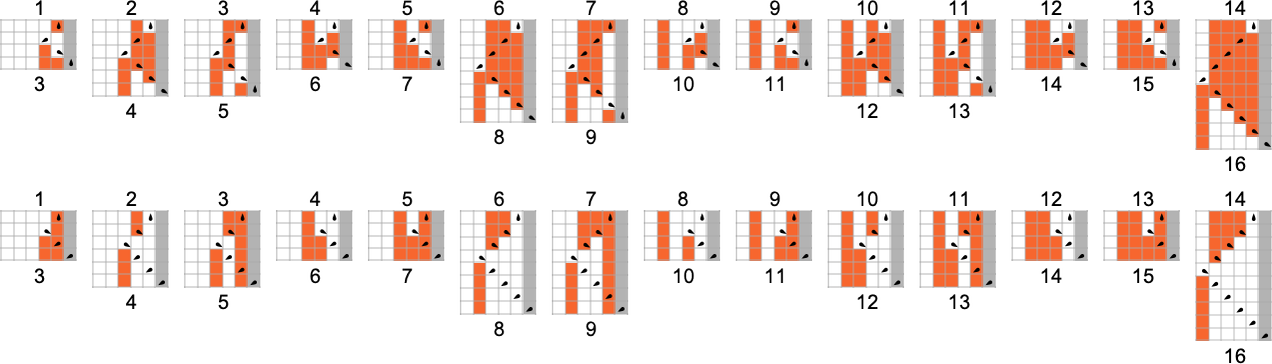

Nondeterministic vs. Deterministic Machines

We’ve seen how a nondeterministic machine can in general generate multiple functions, with each output from the function being associated with a minimum (“nondeterministic”) runtime. But how do the functions that a particular nondeterministic machine can generate compare with the functions that deterministic machines can generate? Or, put another way, given a function that a nondeterministic machine can generate (or “compute”), what deterministic machine is required to compute the same function?

Let’s look at the

Can we find a deterministic ![]() ) branch in the multiway system

) branch in the multiway system

so that it inevitably gives the same results as deterministic machine 3.

But (apart from the other trivial case based on following “machine 7” branches) none of the other functions we can generate from this nondeterministic machine can be reproduced by any

What about

And here are the paths through the multiway graphs for that machine that get to these values

with the “paths on their own” being

yielding “nondeterministic runtimes”:

This is how the deterministic

Here are the pair of underlying rules for the nondeterministic machine

and here is the deterministic machine that reproduces a particular function it can generate:

This example is rather simple, and has the feature that even the deterministic machine always has a very small runtime. But now the question we can ask is whether a function that takes a deterministic machine of a certain class a certain time to compute can be computed in a smaller time if its results are “picked out of” a nondeterministic machine.

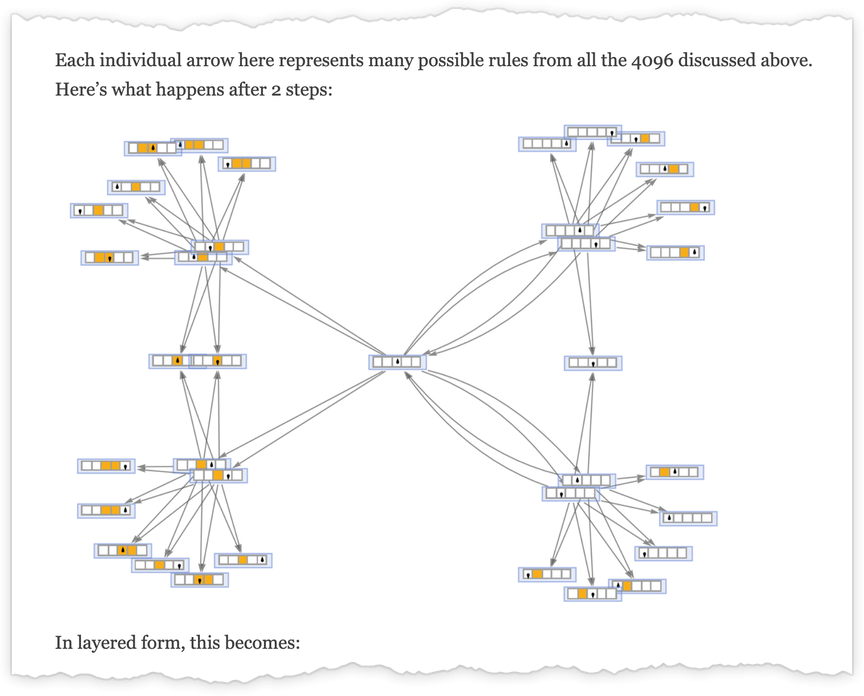

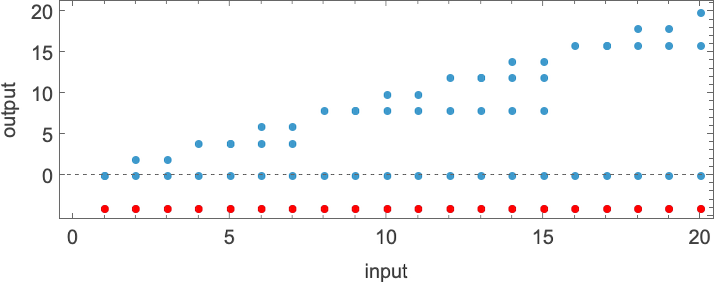

We saw above that

But what about a nondeterministic machine? How fast can this be?

It turns out that there are 15 nondeterministic machines based on pairs of

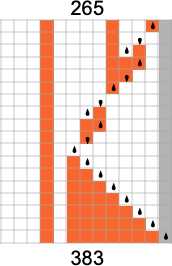

Here are the paths within the multiway graph for the nondeterministic machine that are sampled to generate the deterministic Turing machine result:

And here are these “paths on their own”:

We can compare these with the computations needed in the deterministic machine:

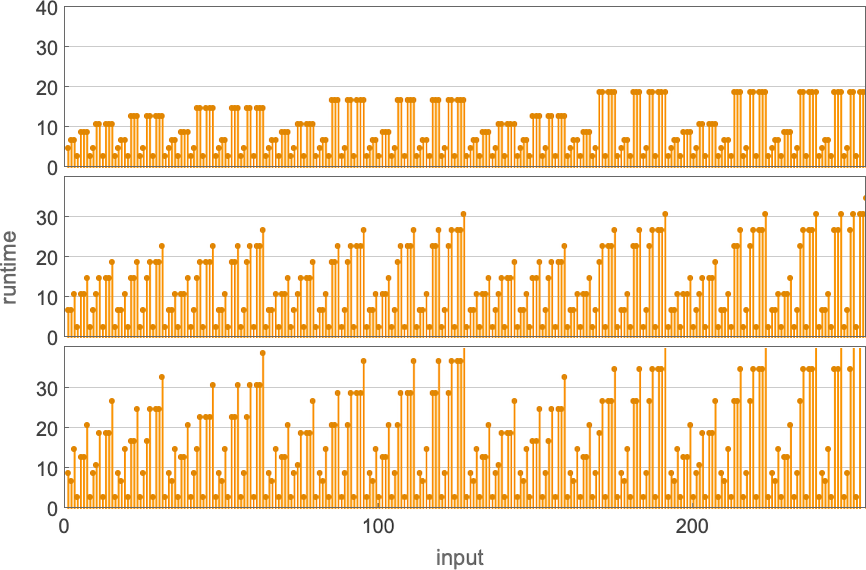

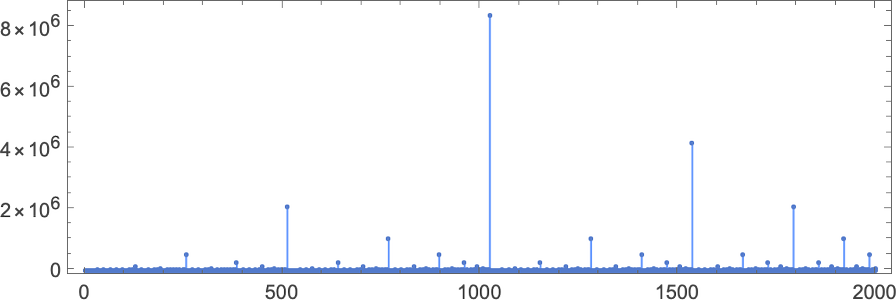

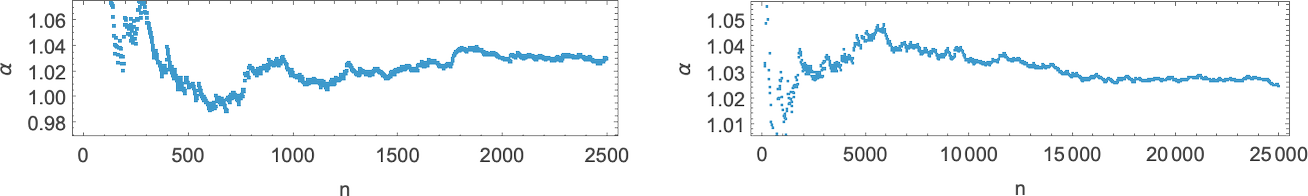

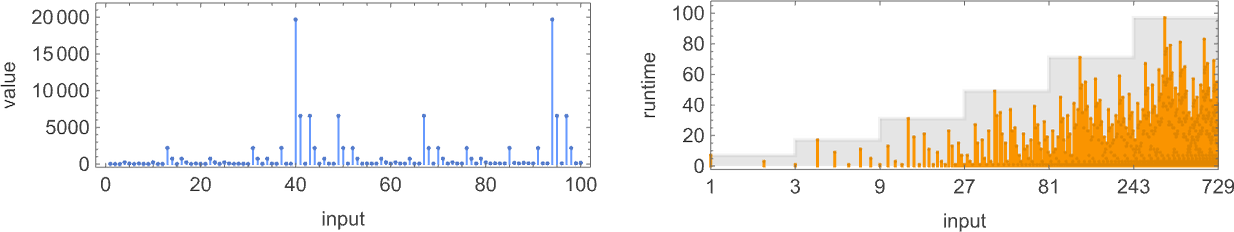

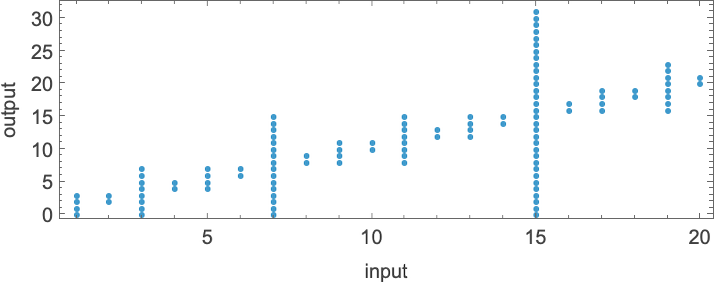

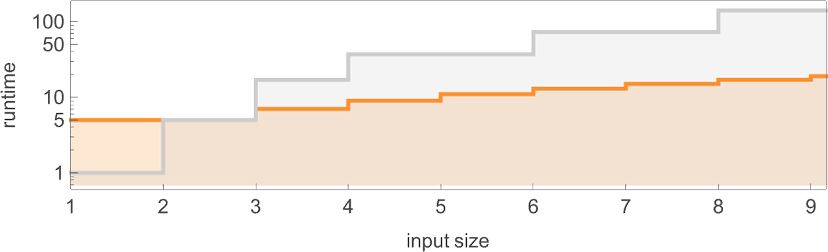

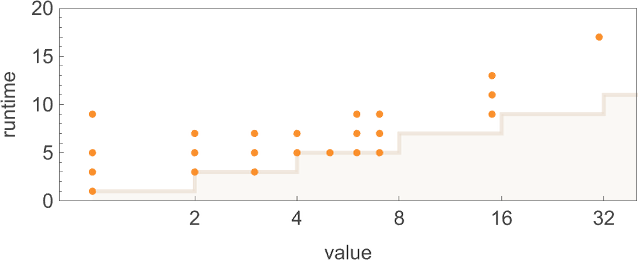

With our rendering, the lengths of the nondeterministic paths might look longer. But in fact they are considerably shorter, as we see by plotting them (in orange) along with the deterministic runtimes (in gray):

Looking now at the worst-case runtimes for inputs of size n, we get:

For the deterministic machine we found above for input size n, this worst-case runtime is given by:

But now the runtime in the nondeterministic machine turns out to be:

In other words, we’re seeing that nondeterminism makes it substantially faster to compute this particular function—at least by small Turing machines.

In a deterministic machine, it’s always the same underlying rule that’s applied at each step. But in a nondeterministic machine with the setup we’re using, we’re independently choosing one of two different rules to apply at each step. The result is that for every function value we compute, we’re making a sequence of choices:

And the core question that underlies things like the P vs. NP problem is how much advantage the freedom to make these choices conveys—and whether, for example, it allows us to “nondeterministically” compute in polynomial time what takes more than polynomial (say, exponential) time to compute deterministically.

As a first example, let’s look at the function computed by the ![]() – 1

– 1

Well, it turns out that the

And indeed, while the deterministic machine takes exponentially increasing runtime, the nondeterministic machine has a runtime that quickly approaches the fixed constant value of 5:

But is this somehow trivial? As the plot above suggests, the nondeterministic machine (at least eventually) generates all possible odd output values (and for even input i, also generates

What makes the runtime end up being constant, however, is that in this particular case, the output f[i] is always close to i (in fact,

There are actually no fewer than

And while all of them are in a sense straightforward in their operation, they illustrate the point that even when a function requires exponential time for a deterministic Turing machine, it can require much less time for a nondeterministic machine—and even a nondeterministic machine that has a much smaller rule.

What about other cases of functions that require exponential time for deterministic machines? The functions computed by the

Something slightly different happens with

The Limit of Nondeterminism and the Ruliad

A deterministic Turing machine has a single, definite rule that’s applied at each step. In the previous sections we’ve explored what’s in a sense a minimal case of nondeterminism in Turing machines—where we allow not just one, but two different possible rules to be applied at each step. But what if we increase the nondeterminism—say by allowing more possible rules at each step?

We’ve seen that there’s a big difference between determinism—with one rule—and even our minimal case of nondeterminism, with two rules. But if we add in, say, a third rule, it doesn’t seem to typically make any qualitative difference. So what about the limiting case of adding in all conceivable rules?

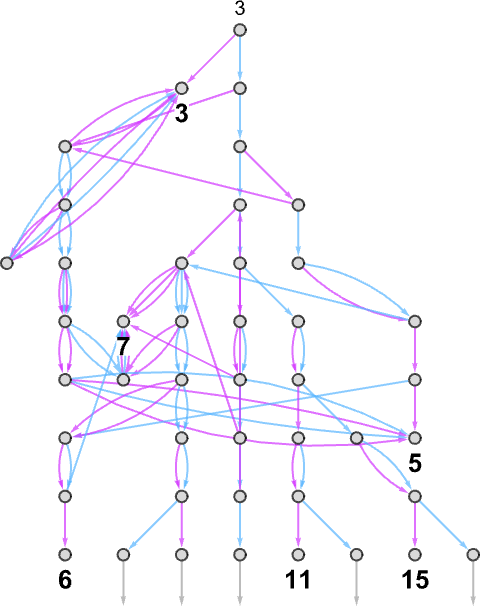

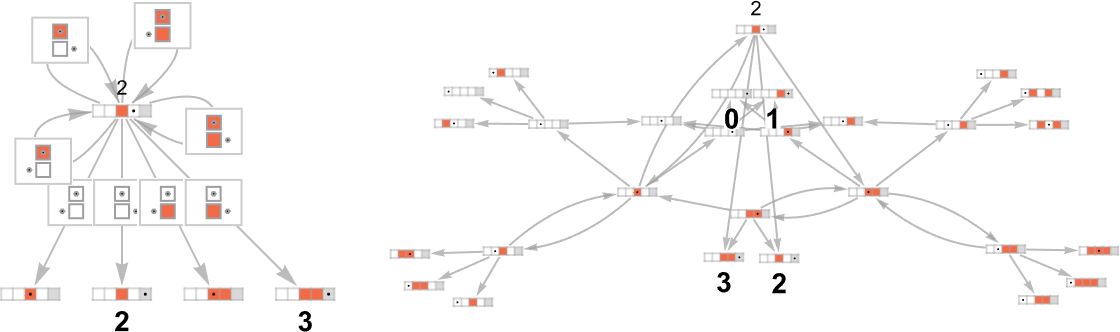

We can think of what we get as an “everything machine”—a machine that has every possible rule case for any possible Turing machine, say for

Running this “everything machine” for one step starting with input 1 we get:

Four of the rule cases just lead back to the initial state. Then of the other four, two lead to halting states, and two do not. Dropping self-loops, going another couple of steps, and using a different graph rendering, we see that outputs 2 and 3 now appear:

Here are the results for input 2:

So where can the “everything machine” reach, and how long does it take? The answer is that from any input i it can eventually reach absolutely any output value j. The minimum number of steps required (i.e. the minimum path length in the multiway graph) is just the absolute lower bound that we found for runtimes in deterministic machines above:

Starting with input 1, the nondeterministic runtime to reach output j is then

which grows logarithmically with output value, or linearly with output size.

So what this means is that the “everything machine” lets one nondeterministically go from a given input to a given output in the absolutely minimum number of steps structurally possible. In other words, with enough nondeterminism every function becomes nondeterministically “easy to compute”.

An important feature of the “everything machine” is that we can think of it as being a fragment of the ruliad. The full ruliad—which appears at the foundations of physics, mathematics and much more—is the entangled limit of all possible computations. There are many possible bases for the ruliad; Turing machines are one. In the full ruliad, we’d have to consider all possible Turing machines, with all possible sizes. The “everything machine” we’ve been discussing here gives us just part of that, corresponding to all possible Turing machine rules with a specific number of states and colors.

In representing all possible computations, the ruliad—like the “everything machine”—is maximally nondeterministic, so that it in effect includes all possible computational paths. But when we apply the ruliad in science (and even mathematics) we are interested not so much in its overall form as in particular slices of it which are sampled by observers that, like us, are computationally bounded. And indeed in the past few years it’s become clear that there’s a lot to say about the foundations of many fields by thinking in this way.

And one feature of computationally bounded observers is that they’re not maximally nondeterministic. Instead of following all possible paths in the multiway system, they tend to follow specific paths or bundles of paths—for example reflecting the single thread of experience that characterizes our human perception of things. So—when it comes to observers—the “everything machine” is somehow too nondeterministic. An actual (computationally bounded) observer will be concerned with one or just a few “threads of history”. In other words, if we’re interested in slices of the ruliad that observers will sample, what will be relevant is not so much the “everything machine” but rather deterministic machines, or at most machines with the kind of limited nondeterminism that we’ve studied the past few sections.

But just how does what the “everything machine” can do compare with what all possible deterministic machines can do? In some ways, this is a core question in the comparison between determinism and nondeterminism. And it’s straightforward to start studying it empirically.

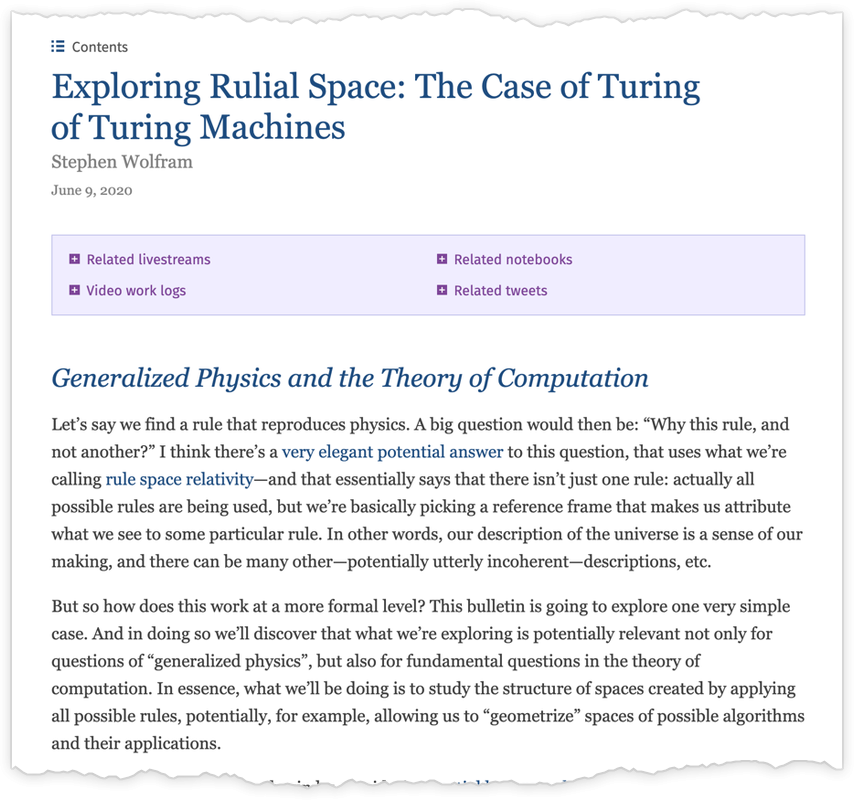

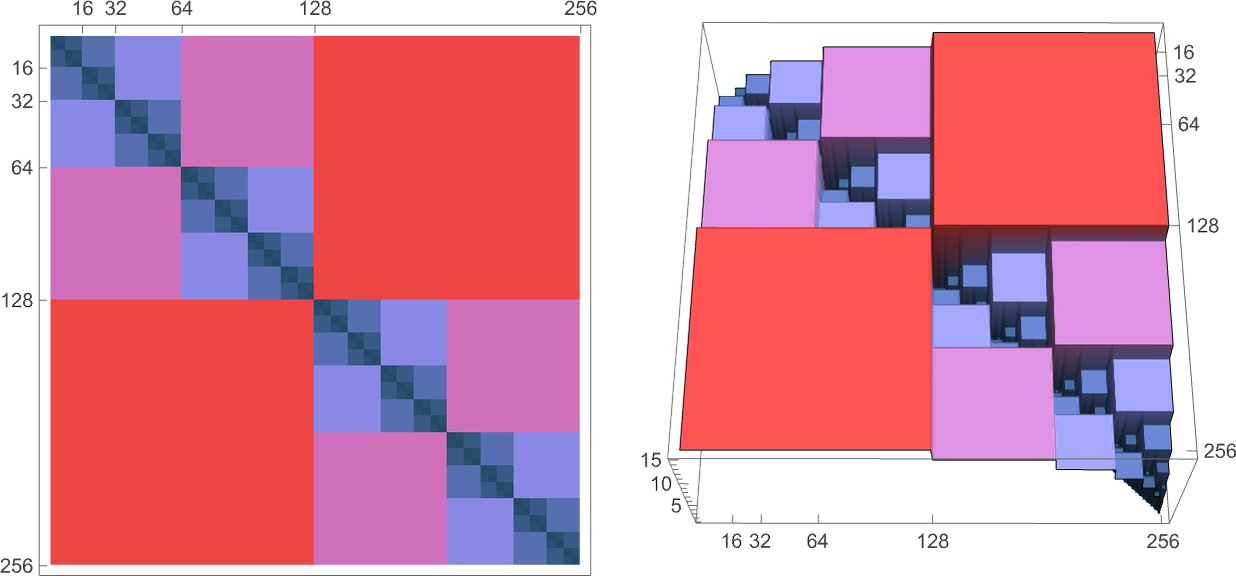

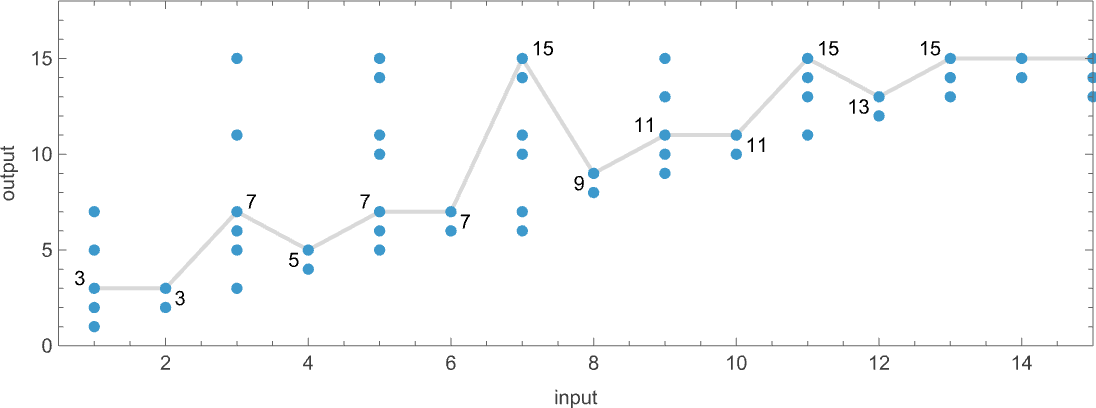

For example, here are successive steps in the multiway graph for the (

In a sense these pictures illustrate the “reach” of deterministic vs. nondeterministic computation. In this particular case, with

For

and the values that can be reached by deterministic machines are:

But how long does it take to reach these values? This shows as dots the possible (deterministic) runtimes; the filling represents the minimum (nondeterministic) runtimes for the “everything machine”:

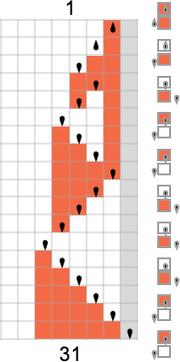

The most dramatic outlier occurs with value 31, which is reached deterministically only by machine 1447, in 15 steps, but which can be reached in 9 (nondeterministic) steps by the “everything machine”:

For

What Does It All Mean for P vs. NP?

The P vs. NP question asks whether every computation that can be done by any nondeterministic Turing machine with a runtime that increases at most polynomially with input size can also be done by some deterministic Turing machine with a runtime that also increases at most polynomially. Or, put more informally, it asks whether introducing nondeterminism can fundamentally speed up computation.

In its full form, this is an infinite question, that talks about limiting behavior over all possible inputs, in all possible Turing machines. But within this infinite question, there are definite, finite subquestions we can ask. And one of the things we’ve done here is in effect to explore some of these questions in an explicit, ruliological way. Looking at these finite subquestions won’t in any direct way be able to resolve the full P vs. NP question.

But it can give us important intuition about the P vs. NP question, and what some of the difficulties and subtleties involved in it are. When one analyzes specific, constructed algorithms, it’s common to see that their runtimes vary quite smoothly with input size. But one of the things we’ve seen here is that for arbitrary Turing machines “in the wild”, it’s very typical for the runtimes to jump around in complicated ways. It’s also not uncommon to see dramatic outliers that occur only for very specific inputs.

If there was just one outlier, then in the limit of arbitrarily large input size it would eventually become irrelevant. But what if there were an unending sequence of outliers, of unpredictable sizes at unpredictable positions? Ultimately we expect all sorts of computational irreducibility, which in the limit can make it infinitely difficult to determine in any particular case the limiting behavior of the runtime—and, for example, to find out if it’s growing like a polynomial or not.

One might imagine, though, that if one looked at enough inputs, enough Turing machines, etc. then somehow any wildness would get in some way averaged out. But our ruliological results don’t encourage that idea. And indeed they tend to show that “there’s always more wildness”, and it’s somehow ubiquitous. One might have imagined that computational irreducibility—or undecidability—would be sufficiently rare that it wouldn’t affect investigations of “global” questions like the P vs. NP one. But our results suggest that, to the contrary, there are all sorts of complicated details and “exceptions” that seem to get in the way of general conclusions.

Indeed, there seem to be issues at every turn. Some are related to unexpected behavior and outliers in runtimes. Some are related to the question of whether a particular machine ever even halts at all for certain inputs. And yet others are related to taking limits of sizes of inputs versus sizes of Turing machines, or amounts of nondeterminism. What our ruliological explorations have shown is that such issues are not obscure corner cases; rather they are generic and ubiquitous.

One has the impression, though, that they are more pronounced in deterministic than in nondeterministic machines. Nondeterministic machines in some sense “aggregate” over paths, and in doing so, wash out the “computational coincidences” which seem ubiquitous in determining the behavior of deterministic machines.

Certainly the specific experiments we’ve done on machines of limited size do seem to support the idea that there are indeed computations that can be done quickly by a nondeterministic machine, but for which in deterministic machines there are for example at least occasional large runtime outliers, which imply longer general runtimes.

I had always suspected that the P vs. NP question would ultimately get ensnared in issues of computational irreducibility and undecidability. But from our explicit ruliological explorations we get an explicit sense of how this can happen. Will it nevertheless ultimately be possible to resolve the P vs. NP question with a finite mathematical-style proof based, say, on standard mathematical axioms? The results here make me doubt it.

Yes, it will be possible to get at least certain restricted global results—in effect by “mining” pockets of computational reducibility. And, as we already know from what we have seen repeatedly here, it’s also possible to get definite results for, say, specific (ultimately finite) classes of Turing machines.

I’ve only scratched the surface here of the ruliological results that can be found. In some cases to find more just requires expending more computer time. In other cases, though, we can expect that new methodologies, particularly around “bulk” automated theorem proving, will be needed.

But what we’ve seen here already makes it clear that there is much to be learned by ruliological methods about questions of theoretical computer science—P vs. NP among them. In effect, we’re seeing that theoretical computer science can be done not only “purely theoretically”—say with methods from traditional mathematics—but also “empirically”, finding results and developing intuition by doing explicit computational experiments and enumerations.

Some Personal Notes

My efforts on what I now call ruliology started at the beginning of the 1980s, and in the early years I almost exclusively studied cellular automata. A large part of the reason was just that these were the first types of simple programs I’d investigated, and in them I had made a series of discoveries. I was certainly aware of Turing machines, but viewed them as less connected than cellular automata to my goal of studying actual systems in nature and elsewhere—though ultimately theoretically equivalent.

It wasn’t until 1991, when I started systematically studying different types of simple programs as I embarked on my book A New Kind of Science that I actually began to do simulations of Turing machines. (Despite their widespread use in theoretical science for more than half a century, I think almost nobody else—from Alan Turing on—had ever actually simulated them either.) At first I wasn’t particularly enamored of Turing machines. They seemed a little less elegant than mobile automata, and had much less propensity to show interesting and complex behavior than cellular automata.

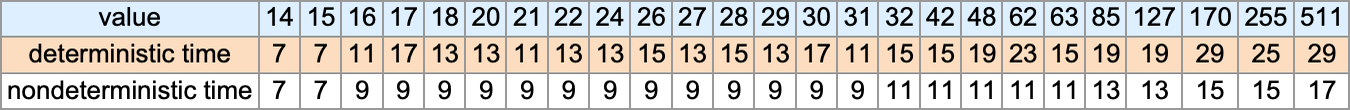

Towards the end of the 1990s, though, I was working to connect my discoveries in what became A New Kind of Science to existing results in theoretical computer science—and Turing machines emerged as a useful bridge. In particular, as part of the final chapter of A New Kind of Science—“The Principle of Computational Equivalence”—I had a section entitled “Undecidability and Intractability”. And in that section I used Turing machines as a way to explore the relation of my results to existing results on computational complexity theory.

And it was in the process of that effort that I invented the kind of one-sided Turing machines I’ve used here:

I concentrated on the s = 2, k = 2 machines (for some reason I never looked at s = 1, k = 2), and found classes of machines that compute the same function—sometimes at different speeds:

And even though the computers I was using at the time were much slower than the ones I use today, I managed to extend what I was doing to s = 3, k = 2. At every turn, though, I came face to face with computational irreducibility and undecidability. I tried quite hard do things like resolve the exact number of distinct functions for

Nearly three decades later, I think I finally have the exact number. (Note that some of the details from A New Kind of Science are also different from what I have here, because in A New Kind of Science I included partial functions in my enumeration; here I’m mostly insisting on total functions, that halt and give a definite result for all inputs.)

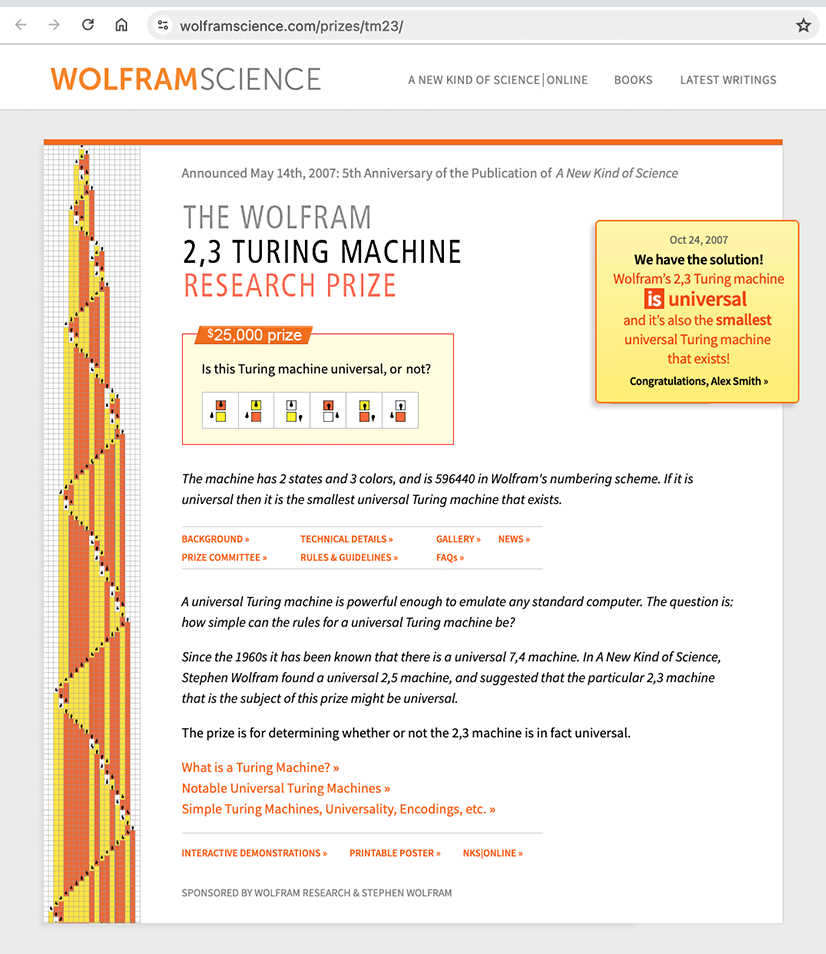

After A New Kind of Science was released in 2002, I made another foray into Turing machines in 2007, putting up a prize on the fifth anniversary of the book for a proof (or refutation) of my suspicion that s = 2, k = 3 machine 596440 was capable of universal computation. The prize was soon won, establishing this machine as the very simplest universal Turing machine:

Many years passed. I occasionally suggested projects on Turing machines to students at the summer research program we started in 2003 (more on that later…). And I participated in celebrations of Alan Turing’s centenary in 2012. Then in 2020 we announced the Wolfram Physics Project—and I looked at Turing machines again, now as an example of a computational system that could be encoded with hypergraph rewriting, and studied using physics-inspired causal graphs, etc.:

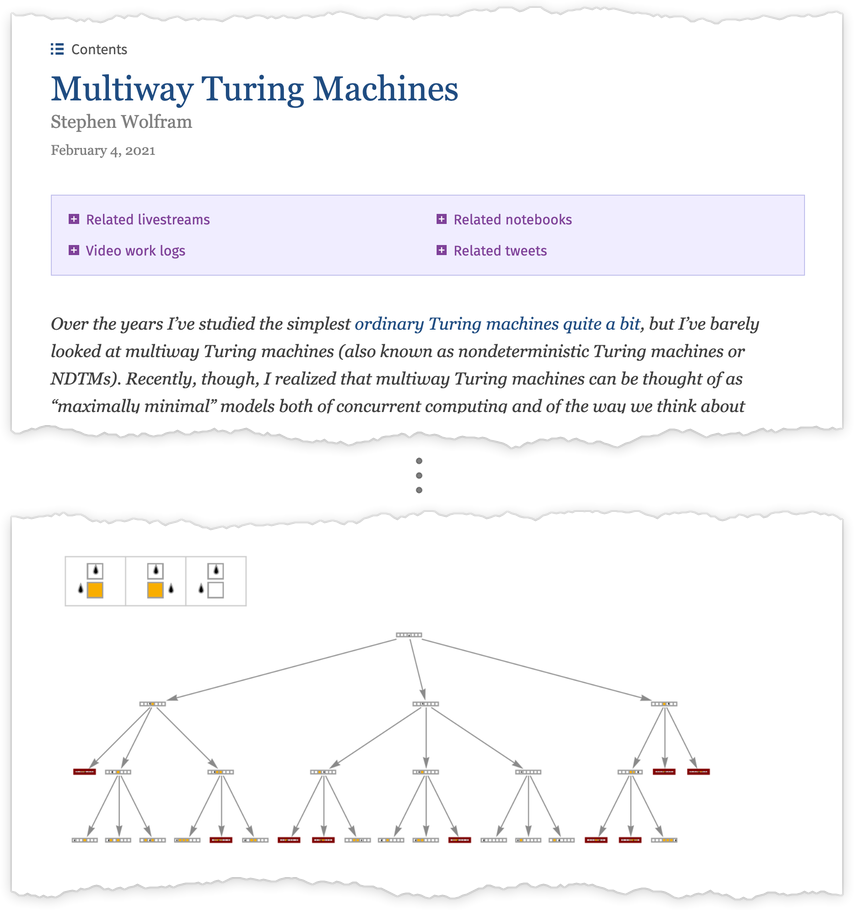

Less than two months after the launch of our Physics Project I was studying what I now call the ruliad—and I decided to use Turing machines as a model for it:

A crucial part of this was the idea of multiway Turing machines:

I’d introduced multiway systems in A New Kind of Science, and had examples close to multiway Turing machines in the book. But now multiway Turing machines were more central to what I was doing—and in fact I started studying essentially what I’ve here called the “everything machine” (though the details were different, because I wasn’t considering Turing machines that can halt):

I also started looking at the comparison between what can be reached deterministically and nondeterministically—and discussed the potential relation of this to the P vs. NP question:

By the next year, I was expanding my study of multiway systems, and exploring many different examples—with one of them being multiway Turing machines:

Soon I realized that the general approach I was taking could be applied not only to the foundations of physics, but also to foundations of other fields. I studied the foundations of mathematics, of thermodynamics, of machine learning and of biology. But what about the foundations of theoretical computer science?

Over the years, I’d explored the ruliology of many kinds of systems studied in theoretical computer science—doing deep dives into combinators for their centenary in 2020, as well as (last year) into lambdas. In all these investigations, I was constantly seeing concrete versions of phenomena discussed in theoretical computer science—even though my emphasis tended to be different. But I was always curious what one might be able to say about central questions in theoretical computer science—like P vs. NP.

I had imagined that the principal problem in doing an empirical investigation of something like P vs. NP would just be to enumerate enough cases. But when I got into it, I realized that the shadow of computational irreducibility loomed even larger than I’d imagined—and that even within particular cases it could be irreducibly difficult to figure out what one needed to know about their behavior.

Fairly late in the project I was trying to look up some “conventional wisdom” about NP problems. Most of it was couched in rather traditional mathematical terms, and didn’t seem likely to have too much to say about what I was doing. But then I found a paper entitled “Program-size versus Time Complexity: Slowdown and Speed-up Phenomena in the Micro-cosmos of Small Turing Machines”—and I was excited to see that it was following up on what I’d done in A New Kind of Science, and doing ruliology. But then I realized: the lead author of the paper, Joost Joosten, had been an (already-a-professor) student at our summer program in 2009, and I’d in fact suggested the original version of the project (though the paper had taken it further, and in some slightly different directions than I’d anticipated).

Needless to say, what I’ve now done here raises a host of new questions, which can now be addressed by future projects done at our summer programs, and beyond….

Note: For general historical background see my related writings from 2002 and 2021.

Thanks

Thanks to Willem Nielsen, Nik Murzin and Brian Mboya of the Wolfram Institute for extensive help. Thanks also to Wolfram Institute affiliate Anneline Daggelinckx, as well as to Richard Assar and Pavel Hajek of the Wolfram Institute for additional help. Work at the Wolfram Institute on this project was supported in part by the John Templeton Foundation.

Additional input on the project was provided by Lenore & Manuel Blum, Christopher Gilbert, Josh Grochow, Don Knuth and Michael Sun. Matthew Szudzik also contributed relevant work in 1999 during the development of A New Kind of Science.